Delft as an Artistic Milieu; Painters 1600-1690

© 2001, Kees Kaldenbach, art historian. Updated February 18, 2009.

--> Blue links

will tell you about life and addresses

of people in Delft <--

-->Another structured way of looking at the info is working the

clickable map and the dropdown

lists<--

-->New in 2002! The Delft

St Luke Guild Book is now online.

In

the seventeenth century Dutch Republic major innovations in the art

of painting took place in various towns such as

Utrecht (a group of painters introducing

Caravaggio's chiaroscuro), in Rotterdam

(introducing genre painting, as in Willem Pietersz Buytewech's

(1591/92-1624) refined interior scenes with Merry Companies; also in

Leiden with Jan van Goyen (1596-1656)

opening up new avenues in landscape and in

Haarlem, where Frans Hals (1581/5-1666)

worked and in Amsterdam where Rembrandt

(1606-1669) developed new ways in portraiture and history

painting.

In

the seventeenth century Dutch Republic major innovations in the art

of painting took place in various towns such as

Utrecht (a group of painters introducing

Caravaggio's chiaroscuro), in Rotterdam

(introducing genre painting, as in Willem Pietersz Buytewech's

(1591/92-1624) refined interior scenes with Merry Companies; also in

Leiden with Jan van Goyen (1596-1656)

opening up new avenues in landscape and in

Haarlem, where Frans Hals (1581/5-1666)

worked and in Amsterdam where Rembrandt

(1606-1669) developed new ways in portraiture and history

painting.

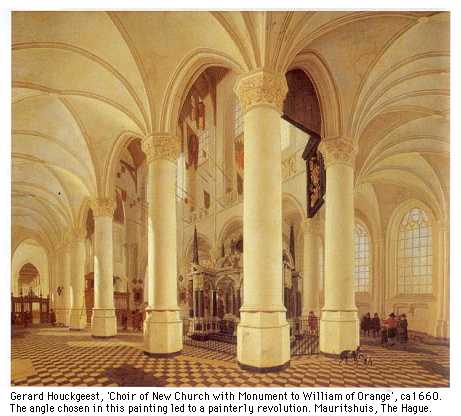

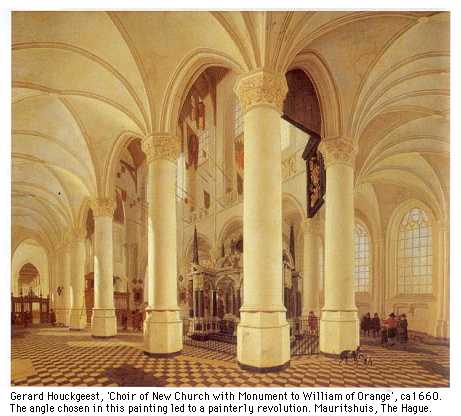

Up to 1650 the painters working in

Delft had largely stayed outside this

breeze of major innovations and thus produced works provincial in

character. Delft however did become the birthplace of a small but

seminal revolution which occurred in 1650 in the field of perspective

painting, a specialization which up to that point was still of minor

local or national importance. This change concerned the manner in

which views of the interiors of local churches were depicted and in

the log run this change proved seminal. The painter who managed to

break this new ground was Gerard

Houckgeest (c. 1600-1661) who may have been born in Den Haag (The

Hague), resided in Delft from 1635-1651, entering the Delft Guild of

St Luke in 1639.  Traditionally

architecture painters depicted a (fantasy) church interior by

presenting a view along the axis of a church, the orthogonal

perspective lines all converging in one single vanishing point which,

according to the rules of the craft, had to be situated on the

horizon line in the far distance. It was normal for church interior

specialists to depict ornate and grand fantasy churches. This well

tested praxis in applying central perspective used since the Italian

Renaissance, was modified by Gerard Houckgeest who shifted his

painterly viewpoint away from the central axis

to one from the side aisle, at the same time presenting an an

actual part of the church in an oblique angle. As a draughtsman and a

painter this meant he first had to work out two diverging vantage

lines which both, one to the left and one to the right hand side,

should touch the horizon line. This more complicated technique

yielded views which looked surprisingly natural and were easy to

grasp for the common viewer. This innovation opened up surprising

avenues of artistic possibilities and shortly other Delft painters

caught on to this new way of presenting viewpoints within

perspective. These painters included the Delft born Hendrick

Willemsz van Vliet (1611/12-1675) who entered the Guild of St

Luke in 1632 and Emanuel de Witte

(1617-1692), a perspective painter, born and trained in Alkmaar,

entering the Delft Guild 1642, and who became head man, leaving for

Amsterdam in 1651. De Witte stood out of this group by stressing

atmospheric effects of light, putting less stress on crisp

perspectival presentation.

Traditionally

architecture painters depicted a (fantasy) church interior by

presenting a view along the axis of a church, the orthogonal

perspective lines all converging in one single vanishing point which,

according to the rules of the craft, had to be situated on the

horizon line in the far distance. It was normal for church interior

specialists to depict ornate and grand fantasy churches. This well

tested praxis in applying central perspective used since the Italian

Renaissance, was modified by Gerard Houckgeest who shifted his

painterly viewpoint away from the central axis

to one from the side aisle, at the same time presenting an an

actual part of the church in an oblique angle. As a draughtsman and a

painter this meant he first had to work out two diverging vantage

lines which both, one to the left and one to the right hand side,

should touch the horizon line. This more complicated technique

yielded views which looked surprisingly natural and were easy to

grasp for the common viewer. This innovation opened up surprising

avenues of artistic possibilities and shortly other Delft painters

caught on to this new way of presenting viewpoints within

perspective. These painters included the Delft born Hendrick

Willemsz van Vliet (1611/12-1675) who entered the Guild of St

Luke in 1632 and Emanuel de Witte

(1617-1692), a perspective painter, born and trained in Alkmaar,

entering the Delft Guild 1642, and who became head man, leaving for

Amsterdam in 1651. De Witte stood out of this group by stressing

atmospheric effects of light, putting less stress on crisp

perspectival presentation.

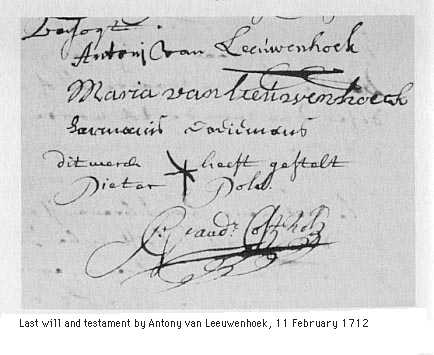

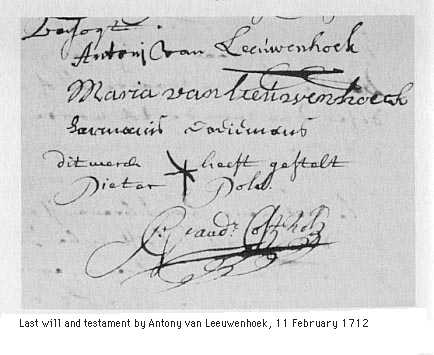

What

seems to have been characteristic of this group of Delft painters in

the 1650's was a common interest in the effects produced by lenses,

which were manufactured by pioneering scientists such as the local

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) who

became famous for his microscope lenses and his research

correspondence with the Royal Society in London.

What

seems to have been characteristic of this group of Delft painters in

the 1650's was a common interest in the effects produced by lenses,

which were manufactured by pioneering scientists such as the local

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) who

became famous for his microscope lenses and his research

correspondence with the Royal Society in London.

Artists analyzed the effects of distortion produced by various

optical devices and studied changes in the intensity of light and

luminosity of color. Within two years this predeliction for

experimentation yielded amazing results in a group of Delft artists.

Foremost amongst this group is history, perspective and still life

painter Carel Fabritius (1622-1654) who

entered the Guild of St. Luke in 1652. His startling View of Delft

with a Music Instrument Dealer shows a view towards the back of

the New Church, the perspective distorted to incorporate a wide angle

of ca. 120 degrees.

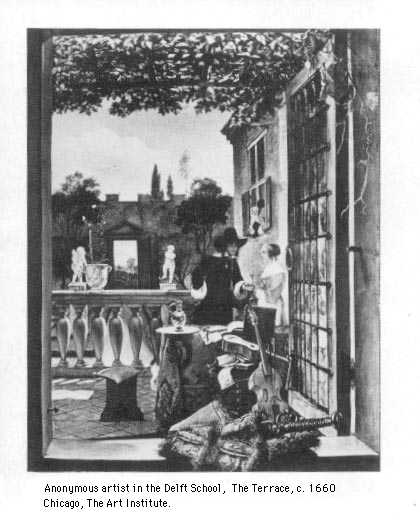

Another artist who experimented with perspective was the landscape

and townscape painter Daniel Vosmaer

(1622-after 1666), who entered in the Guild of St. Luke in 1650. In

1663 he produced a large canvas with a View of Delft from a

Fantasy Loggia, which is equally fascinating in that the painter

succesfully showed the luminous Delft whereas he floundered in

technical points of perspective in depicting the loggia ceiling and

its tiled floor. This work gives us an idea of the mastery of the

wall and ceiling paintings by Fabritius which were applied in various

Delft homes (one in the home of Surgeon Theodorus

Vallensis (1612-1673) at Oude Delft between Nieuwstraat and Oude

Kerk) but which are now all lost.

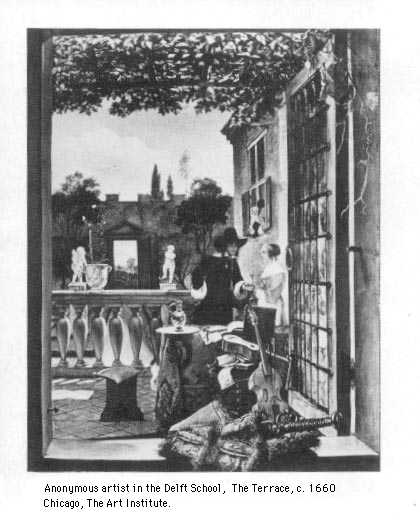

Both painters set new standards for a group of gifted artists

including the upcoming genre painter Pieter

de Hooch (1629-1684) who moved to Delft before 1652 and was to

stay in Delft for almost ten years of his life before moving to

Amsterdam. In Delft De Hooch produced scores of unparalelled

paintings, mainly of refined burghers and their personnel or children

in either light filled rooms or courtyards.

There must have been just the right critical

mass of artistic drive and know how and the right formula of

patronage and art market within Delft to make such a tremendous

success occur.

In

this atmosphere of artistic competition for new ways of depicting

life applying optimal illusionistic effects

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, see entries

Vermeer 1, 2,

3, 4,

5) entered the scene. Johannes Vermeer

was artistically trained outside of Delft and must have returned to

Delft by 1656-1657 just when this new artistic fertility in Delft had

matured. Vermeer soon emulated the best local painters, notably

De Hooch, and reached an astonishing peak

producing interior and exterior scenes with spatially fully

convincing perspective views, audacious yet balanced colour hues, and

showing off an almost miraculous mastery in the depiction of the

textures of all manner of materials, whether it be porcelain, glass,

silk, leather, wool or wood. In this he paved the way for followers

such as Cornelis de Man (1621-1706) and

genre painter Hendrick van der Burch /

Burgh (1627-after 1669) who entered the Guild of St. Luke in 1649 and

moved to Leiden in 1655.

In

this atmosphere of artistic competition for new ways of depicting

life applying optimal illusionistic effects

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, see entries

Vermeer 1, 2,

3, 4,

5) entered the scene. Johannes Vermeer

was artistically trained outside of Delft and must have returned to

Delft by 1656-1657 just when this new artistic fertility in Delft had

matured. Vermeer soon emulated the best local painters, notably

De Hooch, and reached an astonishing peak

producing interior and exterior scenes with spatially fully

convincing perspective views, audacious yet balanced colour hues, and

showing off an almost miraculous mastery in the depiction of the

textures of all manner of materials, whether it be porcelain, glass,

silk, leather, wool or wood. In this he paved the way for followers

such as Cornelis de Man (1621-1706) and

genre painter Hendrick van der Burch /

Burgh (1627-after 1669) who entered the Guild of St. Luke in 1649 and

moved to Leiden in 1655.

In analyzing this remarkable artistic heritage of Delft artists we

are discussing remains of a much larger artistic body that was once

created - which is a sobering realization. This is also apparent in

the once architecturally fixed murals and ceiling paintings by

Fabritius. The loss of oil paintings due to the ravages of time has

been estimated between 50% to as high as 90% of all paintings created

in Delft or for that matter elsewhere in The Netherlands, although a

less dramatic loss percentage seems to have hit the works of the

foremost painter Johannes Vermeer.

Geography and politics

Before describing which patrons played a major role and what the

structrure was of the local art marketbe we should first observe

Delft geography and politics in a nutshell as it formed the framework

of local artictic supply and demand.

Situated in the southwestern corner of the Province of Holland,

the Dutch town of Delft and its region grew strong and prosperous

during the fifteenth and sixteenth century. Delft became the

preferred seat of William the Silent (1533-84), Prince of Orange,

Stadtholder of the provinces of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht. He

chose Delft because it was a southward facing major garrison

town, holding troops and armaments belonging to three military

powers, being the States General, the Province of Holland and the

town of Delft itself. It was advantageously situated close to the

seat of government in The Hague, which itself lacked

fortifications.

In the 1560's the Dutch subjects confronted their lawful King,

Philips II ( 1527-1598) of Spain with two major demands, one for

freedom to practice the protestant religion, the other for lowered

taxation. The Eighty Years war (1568-1648) was unleashed because of

the harsh Spanish response to both of these unresolved issues. The

momentum of events brought to the Dutch in the end not only religious

freedom but also political independence, first marked in 1581 by the

Acte van Verlatinghe (Act of cesession), precursor of the

Declaration of Independence (1787) of the first thirteen states

founding the United States of America.

A glimpse of military life in Delft is seen in Vermeer's "Officer

and the Laughing Girl" (Frick Collection, NYC), while archival

documents show numerous contacts between Vermeer and military

officers, one of whom, a military engineer, was a family member.

Another military scene, although often not regarded as such, is the

famous View of Delft showing the

major southern fortification walls and gates. As exemplified by the

presence of three separate military forces within seventeenth century

Delft there was a finely tuned division of three political powers.

The provinces were the main political body and formed independent

military members of the Republic. Together the seven northern

Netherlandish provinces formed a loose confederation, the "Republic

of the Seven United Provinces", jointly instituting the national

'umbrella' body of the States-General, whose powers were limited to

declaring war, truce, peace and to raising taxes. The towns within

the seven provinces were the actual powerhouses of wealth, trade,

industry and jurisdiction, all jealously guarding their own

prerogatives which had been granted to them by local chieftains in

mediaeval period.

In

the realm of defence we should not forget to mention a separate,

non-military but eqally essential organisation, the Waterschap

(Water and Dyke management HQ) regulating all potentially life

threatening water flows in the low lands of the Republic.

In

the realm of defence we should not forget to mention a separate,

non-military but eqally essential organisation, the Waterschap

(Water and Dyke management HQ) regulating all potentially life

threatening water flows in the low lands of the Republic.

Delft was a small town. In 1628 the population was just under

30.000, comprising only some 3% of all inhabitants of the province of

Holland which counted about a million inhabitants, the total number

of inhabitants of the Republic being about 2 million inhabitants.

Within the province of Holland, itself by far the most important one

in the Republic, Delft was nevertheless pivotal

in defence and thus one of the six towns with a major say in

the affairs of the province of Holland and thus - by proxy - in the

States general.

Rich burghers

The Delft region had grown prosperous during the fifteenth century

by an astounding number of beer

breweries whose grand production figures declined in the

sixteenth century due to expensive ingredients and decreasing sales

to Flanders. Increased development of the black woolen cloth industry

and foreign trade brought new activities. When in the 1620's and

1630's demand for Chinese porcelain far outstripped supply, the Delft

faience industry succeeded in producing a faience which imitated the

expensive and sought after original porcelain material. This Delft

Blue faience industry took off with a flying colours from the 1630's

onwards, providing work for many inhabitants in 30

separate Delft Blue workshops.

Mainstays of economy during the seventeenth centrury were sea

fishery, in which the richest catch was herring. This trade is

exemplified by two herring ships, each called buis (bus/buss) which

are visible to the far right of Vermeers painting The

View of Delft. Recently an essay was published in which these

ships help date the scene of this painting to the first half of May

1660 or 1661.

Inland fishery provided another rich source of protein, its

product being sold daily -except sundays- at the visbanken near

Hippolytusbuurt near teh Market Square. The staple foods for the

populace came from farming. Farm produce was transported by water to

the local Delft markets. Around Delft numerous vegetable fields and

animal barns provided vegetables and meats for the weekly markets in

town. Vegetable farms in the Republic boasted a high yield per acre

as a result of advanced methods for nursery, soil, manure and water

management, all geared towards production for the needs of the

market. Grains and other staple foods were however imported by Dutch

traders from the Baltic region as it was more economic to do so.

The province of Holland once consisted of low lying waterlogged

woodlands and peat lands which were reclaimed from the sea by

building dykes and windmill driven water pumps and removing the peat.

This activity resulted in shrinkage of the once waterlogged land,

thus a dramatic lowering and settling of the flatlands by sometimes

more than a few meters, necessitating a continuous process of water

engineering throughs canals and ditches. In Delft countryside and

town were interlinked by these waters as can be seen on detailed maps

of the region. The east-west running canals within Delft follow the

pattern of east-west running ditches and canals in the surrounding

landscape; it indicates how the town of Delft grew organically out of

the grid existing in the farmland countryside.

South harbour

The Dutch United East India Company

(VOC) was founded in 1602 by local Kamers (Chambers) located in

six harbour towns in the provinces of Holland and Zeeland. The

Amsterdam Chamber was by far the largest and the Delft Chamber (VOCD)

one of the minor ones. Each Chamber was represented by one or more

seats in the central board, the 'Heeren XVII' (Governors seventeen).

Far reaching powers were given to this central board with regard to

setting up trading posts, outfitting forts and making treaties with

local rulers in far away countries. Thus the powers of the VOC abroad

resembled that of a state. Total number of employees reached

___(check) in 16??___(check).

In the course of time the Delft Chamber built and prepared a

total of thirty ships for the voyage

eastward in de period 1602-1650. In the following years on average

one to two ships per year were sailed out of Delfshaven. Later on

this number even increased. Buying stock in the VOC meant a high risk

investment as ships could founder, but a succesful arrival of return

cargo of spices such as pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves and of

products such as chinese porcelain meant a royal return of

investment.

VOC Delft operated from two locations. The major one, the

'Oost Indisch Huis' (East India House

HQ) was in Delft at Oude Delft, near the southern harbour. This was

the management and the storage facility for the costly goods.

Straight across the water was the East India Warehouse whose hoisting

tackle could reach the holds of the ships as that building was right

on the water's edge. The other location of VOCD was in Delfshaven,

Delfts own harbour on the Maas river. The warehouse building erected

there in 1672 served as storage for everything a ship would need when

going on a long eastward voyage. Delfshaven also was the location of

the major shipbuilding yard and the home base of the herring fleet.

Upon return of a great East India ship goods were offloaded near

Delfshaven into smaller inland ships which sailed to the Delft

location for storage and distribution. note. De VOCD was doing

excellent businiss during the first decades.

Because of these growing commercial pressures the south harbour of

Delft soon proved to be too small and too shallow so that Town Hall

decided to build a new and wider harbour. The entire area naer

Schiedam and Rotterdam gates were remodeled in 1614. The land

abutment on thich the former barbican of the Schiedam gate (this is

the gate building in the middle of the View of Delft) was shortened

and turned into a pier. West of Schiedam gate a new smaller gate was

built which allowed entry of horse drawn coaches (see full

description of Vermeers View of

Delft).

With room to expand traffic the interior shipping blosomed in the

Delft region.The View of Delft Vermeer from 1660-1661 shows a recent

innovation, depicting tow barges,

one situated close by to the left, the others far away by the bridge.

For public transportation to The Hague or towns as far as Haarlem and

Amsterdam a unique system of canals was installed in which tow barges

were pulled by a horse which trod on a tow path on one side of the

canal. Two major periods of canal building with its necessary

secondary systems of bridges, sluices and tow paths took place, one

starting at 1632, the other from 1655 onwards. The Schie canal going

south from Delft to Delfshaven/Rotterdam was part of the latter drive

and received its tow path in 1655 on its western embankment. Although

managing the barges was an investment driven for-profit operation the

Town Hall took firm control, regulating the time schedule during day

light hours, ticket prices, an annual quality control of the barges

and other regulations. As in other branches of Delft economic life a

commissioner was appointed by the Town Hall, always being a family

member of one of the the influential Council of Fourty. For the

commissioner in charge the work entailed was minimal, and the yearly

income more than appreciable, making it a coveted sinecure, an easy

income. Less handsome pay went to the shipping company and its

personnel, for each tow boat a skipper and a young boy leading the

horse.

For longer distance travel during day and night time and for

traffic across the Zuyder sea a different network of sailing ships

which also served towns according to a schedule approved by Town

Hall.

Town Hall

Local

wealth was trumpeted by the brand new Delft Town

Hall on Markt square, rebuilt in 1620 by architect Hendrick de

Keijzer (1565-1621) in a Dutch renaissance style which sought to

impress. This edifice dominates central Markt (Market sqare) by

emanating grandeur through its classical ordonnance, whereas its rich

ornament exults a festive mood. After a fire in 1618 wrecked the old

Town Hall it was rebuilt, maintaining as a core the central mediaeval

keep of the old town hall, which stick out like an alien part from

the western end. Within the town hall convened the four Burgomasters

and the aldermen, which were appointed by the all powerful

'Veertigraad' (council of fourty) alias 'Vroedschap'

(council of wisdom), aptly defined as 'the group of fourty burghers

among whom burgomasters and aldermen were co-opted'. These council

men, all members of factions made up of powerful local families,

gained entry to the top through money and politics. For a family to

move to the center of power it took decades of shrewd politics which

included seeking financial gain through well-paid municipal

functions, by dealings with other influential families and by

establishing marriage relationships between families. The tension

which occurred in the 1570's between the old established Roman

Catholic Church and the upcoming protestant groups inspired by Martin

Luther (1483-1546) and most of all by John Calvin (1509-1564) put

matters of religion in the forefront of political affairs as the

catholic faith was associated with the Spanish King and bloody

suppression and the protestant faith was associated with a struggle

for religious freedom.

Local

wealth was trumpeted by the brand new Delft Town

Hall on Markt square, rebuilt in 1620 by architect Hendrick de

Keijzer (1565-1621) in a Dutch renaissance style which sought to

impress. This edifice dominates central Markt (Market sqare) by

emanating grandeur through its classical ordonnance, whereas its rich

ornament exults a festive mood. After a fire in 1618 wrecked the old

Town Hall it was rebuilt, maintaining as a core the central mediaeval

keep of the old town hall, which stick out like an alien part from

the western end. Within the town hall convened the four Burgomasters

and the aldermen, which were appointed by the all powerful

'Veertigraad' (council of fourty) alias 'Vroedschap'

(council of wisdom), aptly defined as 'the group of fourty burghers

among whom burgomasters and aldermen were co-opted'. These council

men, all members of factions made up of powerful local families,

gained entry to the top through money and politics. For a family to

move to the center of power it took decades of shrewd politics which

included seeking financial gain through well-paid municipal

functions, by dealings with other influential families and by

establishing marriage relationships between families. The tension

which occurred in the 1570's between the old established Roman

Catholic Church and the upcoming protestant groups inspired by Martin

Luther (1483-1546) and most of all by John Calvin (1509-1564) put

matters of religion in the forefront of political affairs as the

catholic faith was associated with the Spanish King and bloody

suppression and the protestant faith was associated with a struggle

for religious freedom.

After the alteratie - the changeover of power within each

town from Roman Catholic to Reformed hands, which occured in Delft in

the week between July 26 and August 3, 1572, the Delft Council of

Fourty only consisted of persons adhering to the Reformed Church

(source for date: H.H. Janus, Hervormd Delft,

Amsterdam 1950, p. 30).

The

interior of the town hall had to be of

a centrain grandeur in order to impress the population and visitors

of the elevated position and status of the town. Thus from 1620

onwards the marble floored town hall rooms were adorned with

paintings, tapestries, fine furniture, maps and prints. At least one

of these paintings was produced by the succesful, though now

considered minor, history painter Corstiaen

van Couwenbergh (1604-1667). In 1638 he received a commission

from the town government in to deliver this painting, for which he

was paid 800 guilders, a sum equal to a good annual income for an

artisan or craftsman. Van Couwenbergh was a succesful history painter

in the manner of the Utrecht painter Gerard van Honthorst

(1590-1656), who in turn was influenced by the Italian painter

Caravaggio (1573-1610). Van Couwenbergh's large history paintings,

often with nude figures, also adorned palaces of the Stadtholder. As

a young man Van Couwenbergh worked in 1630's for Stadtholder Prince

Frederik Hendrik; and in 1640's Van Couwenbergh became a member of

the international team of artists working on the famous cycle of

paintings on the theme of the Triumph of Frederik Hendrik in the hall

of Huis ten Bosch, The Hague. Van Couwenbergh's wealth and social

position was such that he could marry Burgomaster's daughter

Elisabeth van der Dussen in 1630. The newlyweds moved into an

important mansion on the east side of Oude Delft canal just south of

Peperstraat, worth 12,700 guilders, which even in elevated Delft

circles was a high price in those days.

The

interior of the town hall had to be of

a centrain grandeur in order to impress the population and visitors

of the elevated position and status of the town. Thus from 1620

onwards the marble floored town hall rooms were adorned with

paintings, tapestries, fine furniture, maps and prints. At least one

of these paintings was produced by the succesful, though now

considered minor, history painter Corstiaen

van Couwenbergh (1604-1667). In 1638 he received a commission

from the town government in to deliver this painting, for which he

was paid 800 guilders, a sum equal to a good annual income for an

artisan or craftsman. Van Couwenbergh was a succesful history painter

in the manner of the Utrecht painter Gerard van Honthorst

(1590-1656), who in turn was influenced by the Italian painter

Caravaggio (1573-1610). Van Couwenbergh's large history paintings,

often with nude figures, also adorned palaces of the Stadtholder. As

a young man Van Couwenbergh worked in 1630's for Stadtholder Prince

Frederik Hendrik; and in 1640's Van Couwenbergh became a member of

the international team of artists working on the famous cycle of

paintings on the theme of the Triumph of Frederik Hendrik in the hall

of Huis ten Bosch, The Hague. Van Couwenbergh's wealth and social

position was such that he could marry Burgomaster's daughter

Elisabeth van der Dussen in 1630. The newlyweds moved into an

important mansion on the east side of Oude Delft canal just south of

Peperstraat, worth 12,700 guilders, which even in elevated Delft

circles was a high price in those days.

The Oude Delft canal, home of most family members of the Council

of Fourty, runs all the way from north-south through Delft. Its

eastern parallel canal is also a continuous body of water but it goes

by a series of names: starting in the south it is called Geer,

Koornmarkt, Wijnhaven, Hippolytisbuurt and finally Voorstraat. Both

canals, constitute the backbone of the wealthy district, especially

the Oude Delft between the Old Church and the southern harbour was

the most sought after real estate location, boasting the major and

festive building of the local waterschap, the Hoogheemraad van

Delfland. Yet in the inner courtyards towards the fortifications

cheap housing was available.

In 1643-1645 the town of Delft paid Van

Couwenbergh another sum of 174 guilders for preparing design

cartoons for tapestries which were to be executed in a famous Delft

tapestry workshop. In 1648 he sold his house at Oude Delft (including

some of the furnishings and paintings as the price would indicate)

for 30.000 guilders. Corstiaen had by then already moved away from

Delft to The Hague, leaving as a legacy not only his fine works of

art but also a large unsettled bakery bill and an even larger bill

from the wine merchant.

The Guild; training period

Van Couwenbergh had entered as a

Master in the Guild of St. Luke in 1627. By law membership of the

Guild of one's particular profession was a prerequisite, allowing a

master to work and teach and trade independently, which in the case

of a painter meant to paint and sell paintings at will. Dutch

municipal guild ordonnances were the legal backbone of this closed

shop Guild system. For entry into the Guild of St Luke a formal six

year training in the workshop of a registered Master of the Guild was

a prerequisite. An entrance fee of 12 guilders was charged to

outsiders and 6 guilders for sons of local Masters, and even 3

guilders if they were trained by their own father. Such was the

enforced regulation. But what to think of the few names who cannot be

pinpointed in the Guild lists? Might they have had another prime

trade?

Education

of a new generation of painters was of prime interest to the Guild.

For parents of a twelve or thirteen year old boy with an aptitude for

drawing it was a very costly undertaking to decide to pay for the

full six years of apprenticeship. During the lengthy painter's

training hardly any income was generated - as opposed to most other

kinds of trades during which the apprentice would immediately do

practical labour, producing goods, earning an income right away. But

a painter's education was a six years investment yielding a result

which was far from certain because of its artistic nature. A natural

aptitude of the trainee shown at the age of twelve or thirteen was no

guarantee for becoming a skilled and artistic craftsman.

Education

of a new generation of painters was of prime interest to the Guild.

For parents of a twelve or thirteen year old boy with an aptitude for

drawing it was a very costly undertaking to decide to pay for the

full six years of apprenticeship. During the lengthy painter's

training hardly any income was generated - as opposed to most other

kinds of trades during which the apprentice would immediately do

practical labour, producing goods, earning an income right away. But

a painter's education was a six years investment yielding a result

which was far from certain because of its artistic nature. A natural

aptitude of the trainee shown at the age of twelve or thirteen was no

guarantee for becoming a skilled and artistic craftsman.

The typical painter could expect to earn an income of between 1000

and 2500 a year. This compares very favourably to the income of a

master in many other trades, earning about 2 guilders a day in

Holland. For those masters about 250-280 working days per annum would

yield 500 to 600 guilders. About 80 percent of households did not

exceed an income of 600 guilders. Thus this risky path to a possible

extremely high payed artistic glory was predominantly chosen by

fathers who were themselves painter or trader in paintings (as in the

case of the father of Johannes

Vermeer). Some Delft goldsmiths or silversmiths also tried their

son's long term luck (see Couwenbergh,

Mierevelt, Vosmaer)

but only a few sons of brewers (Van der

Hoef, Van der Vin) risked this line of

work.

We find some exceptional instances in Delft where artisans managed

to pay for the training of their sons sons. A sail maker managed the

tuition cost for two sons, fruit still-life painter Gillis

de Bergh (before 1606-after 1669) who entered the Guild of St.

Luke in 1624 and his brother, history painter Matheus

de Berg (c.1615 -1687) who entered the Guild 1638, becoming head

man in 1649. His succesful upward social mobility resulted in his

ability to put his own son through law school.

Sons of the upper class burghers on the other hand were normally

destined to also become notaries, doctors and lawyers. They did not

aspire to be trained for the manual labour of an artist, although in

exceptional cases wealthy burghers took up the art of painting

themselves. Three examples of are jonkheer (esquire) Arent

van Reijnoij who lived at north side of Nieuwe Langendijk in a

house with five hearths. He entered St Lukes Guild in 1613 or before

as a wealthy amateur of art, owning a fine collection. Willem

van Roscam (?-1643), embroiderer and Pieter

Adraen den Dorst entered guild of St Luke in 1613 or right after.

One would also expect the latter two to have owned an appreciable

private collection of prints and drawings. In their case there was

also no clear distinction between who was an artist and who was a

patron.

Apprenticeship of boys was arranged not by the Guild but by a

private contract between master and trainee or the parents of the

trainee; archival research has yielded four of these contracts. One,

dating from 1620 set down the duties and rights of master painter

Harmen Arentsz van Bolgersteyn

(1585-1641) and his apprentice Reymbrandt Verboom, who wished to

finish the last two years of his required six years of training.

Master Bolgersteyn had himself entered the Delft Guild of St Luke

between 1613-1617. For an annual sum of 50 guilders he agreed to

train young Verboom and provide all painting materials. For this

price the boy did however not have lodging, but he received all of

the costly painting materials for free and he also had the right to

sell the paintings which he made during his training period.

Another known training contract is that of church interior

perspective painter Emanuel de Witte

(1617-1692). Emanuel de Witte who trained and joined the Guild in

Alkmaar studied in Evert van Aelst's

(1602-1657) workshop along with the fellow trainees Willem

van Aelst (1626-1683) and Adam Pick

(c. 1621-before 1666). Early in 1642 De Witte signed a contract with

his landlord, the brewery foreman Rocus Rocusz

van der Vin (?-1655), renting an upstairs room in Choorstraat

which was leased to him rent free in lieu of teaching the landlords'

fifteen year old son. This unorthodox arrangement was probably set up

as De Witte was officially not entitled to teach at that time as he

was not yet member of the Guild of St Luke. Later in that same year

1642 De Witte did however manage to enter the Delft Guild, staying on

for another nine years before he moved on to Amsterdam in 1651.

The Guild of St Luke of Delft embraced an ever shifting membership

because of new enrollments, of deaths and because of the freedom of

painters to establish themselves at will in other towns. After 1580

there was an appreciable new influx of artists who came from Flanders

(Van Bassen, Van

der Bundel, Van Geel), most of them

seeking to profess their protestant faith. At any singe year from the

1620's to 1650's there were about fifty

painters in Delft constituting a relatively a small body

compared to Dutch towns of similar size. These fifty painters were

not all fine oil paint artists as a number of them were kladschilders

(oil painters in the rough, house painters) and a small number was

water colourist. Within the same Guild there were

other departments which require only

mentioning here in passing, and whose membership excluded that of the

fifty or so painters. These were print colorists, painting and print

sellers, booksellers, needlepoint workers, sculptors, faience

painters, tapestry workers and finally and perhaps rather bizarre, a

separate group of chair painters.

The Guild was regulated by

municipal ordonnance decreed by the burgomaster and aldermen. The day

to day running of the Guild was up to the Head men, the leadership of

the Guild, whose members were rotating year by year, annually elected

by the members. The acting head men sent the proposal of names of the

upcoming and leaving head men slated for the next year to the

Burgomasters and Aldermen who normally agreed to the submission.

Amongst the acting head men are a few outstanding names, three of

whom will be mentioned here.

Cornelis de Man (1621-1706), genre and

landscape painter who entered Guild of St. Luke in 1642, influenced

by De Hooch. His exemplary career shows that he moved in foremost

circles in Delft. De Man had sojourned in Italy, returned to Delft in

1654-55, He became head man of the Guild in 1657 when he was 36 years

old and again took up that post in 1673, 1681 and 1687. He became

Regent of the Orphanage and painted a group portrait of the Surgeons'

Guild and he moved to The Hague in 1706.

Leonaert

Bramer (1596-1674). History painter, also landscape and portrait

painter. Prolific draughtsman. Italian sojourn 1614-before 1628,

mastering the fresco technique. In Guild of St. Luke in 1629, head

man in 1661, 1663, 1665. Sergeant in the Civic Guard; contracted by

the Town government for upkeep of paintings in the Doelen (Civic

Guards) building. Lived in the Wapen van Dantzig (Dantzig

Arms) on 48 Koornmarkt. He probably rented it before 1638 and bought

it in 1643 for 2,500 guilders. In 1653 he was contracted to paint a

fresco in a corridor between his house and that of his neighbor

Bronchorst. In 1648 he bought a house

at north side of Pieterstraat for 910 guilders; lived there in 1658

according to one source, sold two adjacent houses at north side of

Pieterstraat in 1668 for 400 guilders. He lived at Koornmarkt in 1670

and died there.

Leonaert

Bramer (1596-1674). History painter, also landscape and portrait

painter. Prolific draughtsman. Italian sojourn 1614-before 1628,

mastering the fresco technique. In Guild of St. Luke in 1629, head

man in 1661, 1663, 1665. Sergeant in the Civic Guard; contracted by

the Town government for upkeep of paintings in the Doelen (Civic

Guards) building. Lived in the Wapen van Dantzig (Dantzig

Arms) on 48 Koornmarkt. He probably rented it before 1638 and bought

it in 1643 for 2,500 guilders. In 1653 he was contracted to paint a

fresco in a corridor between his house and that of his neighbor

Bronchorst. In 1648 he bought a house

at north side of Pieterstraat for 910 guilders; lived there in 1658

according to one source, sold two adjacent houses at north side of

Pieterstraat in 1668 for 400 guilders. He lived at Koornmarkt in 1670

and died there.

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, see

entries 1, 2,

3, 4,

5) became head man at the exceptional

early age of 30 in 1662, and was called up again in 1670. The reason

for this unprecedented step may have been either the personal

qualities of Vermeer but may also have also been induced by the lack

of proper candidates of a more suitable age. Within the Guild the

recent loss of a number of prominent painters may have caused a local

unbalance. An appreciable loss occurred on 12 October 1654 when the

gunpowder explosion mortally wounded the the multi-talented history,

perspective and still life painter, young Carel

Fabritius (1622-1654). Trained in Rembrandt's studio in

Amsterdam, he joined the Guild of St. Luke in 1652. Initially lived

(with his father in law?) at Oude Delft; later independently at

Doelenstraat near the gunpowder arsenal, causing the artist's death.

In 1675 several of Fabritius's paintings were in Vermeer's

inventory.

In Delft we find Vermeer paintings in the private art collections

of Pieter Claesz van Ruijven, Hendrick

Ariaensz. van Buyten, Johannes de

Renialme, Cornelis van

Assendelft, Cornelis de Helt and

Gerard van Berckel.

Music

The many musical instruments in Vermeers refined interiors makes

one wonder at the role of music life of Delft burghers, painters and

artisans. Delft itself was not a music town par exellence. It lacked

not only a playhouse theater, but also a music hall. Music and

singing songs from printed booklets was however an affair which often

took place in homes and during feasts. Public performances were part

of town life to some degree. During festive occasions pipers and

fiddlers played in the open. One of them was professional musician

Claes Corstiaensz, the second husband

of Vermeer's paternal grandmother Cornelia (alias Neeltge Goris, who

died 1627). After Vermeer's grandfather Jan Reyersz. died in 1597 his

widow Neeltge married Claes Corstiaensz. After his death Vermeers

father and later Vermeer himself must have inherited these

instruments. Thus music and musical instruments became a recurrent

theme in Vermeer paintings. Virginals and harpsichords, especially

those Antwerp built Ruckers instruments shown in Vermeer paintings

were extremely expensive. There were probably not more than a few of

these in Delft. Author Montias* thinks Vermeer's mother in law

Catherina Bolnes had one ; others were

owned by Cornelis Graswinckel

(1582-1664) and Dirk Jansz. Scholl

(1641-1727).

Organ music was performed within churches, resurfacing after a

discussion within the Reformed church between adherents and

hardliners who thought organ music was irredeemably popish in nature.

From 1662 onwards the newly installed carillon of the New Church was

played either automatically on a hourly basis, run by a mechanically

advanced pin and drum system - or manually during certain hours of

the day and during festive occasions. A famous organ player was

Dirk Jansz. Scholl (1641-1727) who

proved to be pivotal in the town's music life.

Wealthy Patrons of the arts

Within the fabric of town one would expect to find the patrons of

the arts to live on the Oude Delft canal and its eastern parallel

canal, with another central node of wealth in and around Markt

square.

Patrons generally did not limit themselves to collecting paintings

and drawings but amassed sought after objects from all over the

world. These collections, known with the German term Kunst und

Wunderkammer could contain coin, cameo and small sculpture

collections, paintings and drawings and animalia and naturalia, the

latter showing a wide, almost encyclopedic interest in the outer

world whose coast lines were discovered and charted in that time.

By far the most prestigeous early Delft art collection is that of

the rich beer brewer Melchior Wyntgis

(15??-1618 or later). He entered Delft 1592, marrying a local

inhabitant. The couple lived In den Oyevaer (in the Stork) at

east side of Voorstraat, owning an outstanding collection of

paintings which was visited by the art connoisseur Aernout Van

Buchell in 1598. Wyntgis sold his Delft brewery for 12.500 guilders

in 1601 and moved out of Delft and later on to Brussels. In an 1618

Brussels inventory listed paintings by major masters: Jan van Eijk,

Hieronymus Bosch and Jan van Scorel. We do not know whether these

outstanding paintings were already in his collection during his Delft

years.

Jan van der Meer (1616-1683).

Apothecary, Head man of his Guild in the 1650's. Lived at Koornmarkt

after 1648. As an avid collector he had ties with East and West India

Company (VOC and WIC) leaders. His collection was visited in 1663 by

Sir Philip Skippon, author of his Account of a Journey...

There he saw a 'museum or a cabinet of varieties' from nature and

antiquity. He also had a garden of rare plants.

Another avid collector of the generation of Vermeer was Hendrik

d'Acquet (1632-1706). Surgeon and Mayor in Delft. He lived at the

west side of Voorstraat and at 202, Oude Delft. He was so proud of

his collection of rarities that he had an inventory catalogue printed

"Insertia et Animalia...". It describes the collection which

he assembled between 1651 and 1703.

Vermeers next door neighbour at Oude Langendijk at the corner

house, west of Molenpoort (now Jozefstraat) was Machteld

van Best (before 1614-1687). In 1632 she married silk merchant

Willen van Erven, active 1653-1677. She inherited an important

Haarlem collection of paintings which included a Cornelis Cornelisz

van Haarlem.

Not only wealthy burghers but also succesful businessmen

collected. Dirck Adriaensz van

Brantwijck ( ?-1646), saw mill owner, contractor, carpenter who

may have lived at west side of Oude Delft. His collection comprised

of of paintings, drawings, prints, rarities and art books. Art books

are books with blank pages for storage of loose prints and drawings.

This entire collection was bequeathed to his brother in law Cornelis

Joosten van 't Woud in 1646.

Eva Briels (before 1609-1659). In

1631 she married the lawyer Nicolaas Bogaert who died first, making

her a wealthy widow. Her own inventory which included some 35

paintings was valued in 1658. Prize posessions were a 'Judgement' by

Abraham J. Bloemaert worth 250 or 350 guilders, and a 'Battle' by

Palamedes worth 200 guilders.

A friend of Johannes Vermeer and his wife Catharina Bolnes was

notary public and art connoisseur Willem

Reyersz de Langue (1599-1656). His portrait is shown as Civic

Guard Sergeant in a full figure double portrait by Jacob W. Delff II.

He lived at north side of Markt possibly at number 38 or 40. Some of

the sketches in the Bramer album (1642-1654) were made from paintings

in his collection.

A major Amsterdam art dealer was of Johannes

de Renialme (c.1600-1657) whose entry in the Guild of St Luke in

1644 allowed him to open a Delft branch of his trade. In 1632 his

branch was in De Clock mette Croon (The Crowned Clock) on the

west side of Dircklangesteeg. A later and more prominent house was on

Oude Delft. Amongst his inventory was the (now lost) Vermeer painting

Een graft besoekende (Three Mary's visiting Christ's Grave),

valued at 20 guilders.

The immediate Vermeer patrons were Pieter

Claesz van Ruijven (1624-1674) and his wife Maria de Knuijt

(16??-1681); they had married in 1653. They

were the major Vermeer patrons, buying his paintings at

perhaps the rate of one a year. In 1657 Pieter and Maria loaned 200

gulden to Johannes Vermeer, presumably as prepayment for paintings.

Vermeer was also mentioned in their legacy as the only artist in or

outside Delft - a token of personal affection. The Van Ruyvens were

independently wealthy, initially owning two houses at Voorstraat

canal, the one on the west side modest in size, the other at the east

side, former brewery De Os (The Ox) larger. In 1660 he also

bought brewery De Gouden Aecker (The Golden Acorn) on

Voorstraat number 39, for 2100 guilders. The couple probably settled

in De Gouden Adelaar (The Golden Eagle), worth 10.500

guilders. Is this the house on the east side of Oude Delft near

Boterbrug? In 1664 and 1665 they still lived at the east side of Oude

Delft. During the last months of his life Van Ruijven lived in The

Hague. In 1680 their daughter Magdalena

married printer and bookseller Jacob

Abrahamsz. Dissius (16??-1695) who became the heir to her fortune

when Magdalena died in 1682. He became the heir to the Van Ruijven

estate but strangely enough he had to share this estate with his

father, Abraham Dissius who died in 1694. After Jacob Dissius himself

died in 1695 the utterly amazing sale of 21 of

the finest Vermeer paintings took place in Amsterdam on 16 May

1696. The Dissius family lived in 'Het vergulde ABC' (Gilded

ABC) at 32, Markt which was bought by Abraham Dissius in 1651.

Not an immediate patron but a keen amateur of the art of Vermeer

anyway was Hendrick Ariaensz. van Buyten

(1632-1701), master baker and head man of the Bakers' Guild in 1668.

Van Buyten became rich throuch inheritances. Diplomat and connoisseur

Balthasar de Monconys visited this 'boulanger' in 1663 to see a

Vermeer painting, featuring one lady, estimated at 600 livres (here:

guilders). Van Buyten had delivered two to three years worth of bread

to the Vermeer family to the total sums of 617 and 109 guilders. In

1676 he agreed with the impoverished widow Catherina Vermeer to

settle this bill with the exchange of two Vermeer paintings. His

final collection of three Vermeers included the large Lady and

Maidservant (now in Frick Collection) and several other paintings by

Delft masters.

Nicolaes van Assendelft (after

1627-1662). His parents who belonged to the marginal group of the

Remonstrant religion, married in 1628. Nicolaes finally became a

"Chirurgijn" (Surgeon) and he published on Harvey's new theory of

blood circulation. (Compare Van

Leeuwenhoek's theory on the same subject!) Nicolaes lived on

Korenmarkt at the time of his early death. He owned the Vermeer

painting "Juffer spelend op Clavecimbel" (Young Lady at the

Clavichord/Virginal) , probably one of the two now in London,

National Gallery.

One of the richest art collector, who visited Vermeer's atelier

twice in 1669 - in order to meet Vermeer and see his works was

Pieter Teding van Berkhout (1643-1713),

member of a foremost family, owning a major fine art collection. In

his diary he wrote that the second time around he saw several

paintings with a curious and extraordinary perspective. Teding became

member of Delft Council of Fourty from 1675 onwards. In 1674 he lived

at Dry Cooningen (Three Magi), Oude Delft number 123. During

his lifetime his wealth in real estate and bonds holdings grew from

90,000 to 475,000 guilders making him exceptionally wealthy. The

family also owned an estate in the countryside just outside

Delft.

Our present list of local collectors of note ends with Judith

Willems van Vliet (? -1650) who had married Jan Jansz Goere in

1632. She lived in De Blauwe Clock (The Blue Clock) at at west

side of Hippolytusbuurt. In her 1650 inventory were 30 paintings

amongst which a Rembrandt worth 60 guilders and a Houckgeest worth 36

guilders.

Female painters were not enrolled in the Guild but they did play a

role in producing paintings in the lower price range - of up to a few

guilders a piece. They were also employed to peddle these or other

paintings in the street. Known female painters in Delft are Cornelia

de Rijck, Maria van

Oosterwyck and her assistant Geertje Pieters.

Then we find Maria van Pruyssen. Of

this group Maria van Oosterwyck has the off position of a highly paid

'art amateur' who was really painting on a professional level.

Text © 2001 copyright Kees Kaldenbach. Last update April 22, 2007.

Appendix

Delft Art world as subdivided by the late John

Michael Montias

Montias* identifies 4 broad groups:

A) Patrons

Wealthy burghers, all living in houses costing 2000 guilders or

more, paying 10 - 25 guilders in annual tax on their home and

bequeathing more than 50 guilders to the Camer van Charitate. Equal

in status to succesful notaries, surgeons, master siversmiths,

succesful merchants.

B) Patrons, Dealers etc.

1) Succesful painters A.

Palamedesz, L. Bramer, M.

Van Mierevelt, all members of the Guild

of St Luke.

2) Wealthy amateurs painter Arent van

Reijnoij, Willem van Roscam,

embroiderer ; Pieter Adraen den Dorst,

also all members of the Guild of St

Luke.

3) art dealers Abraham de Cooge ;

Reynier Jansz Vos/ van der Minne/

Vermeer, father of Johannes Vermeer.

4) Owners of printing presses: Andries

Cloeting, Felix van Sambich de Jonge,

Jan Pietersz Walpoth.

5) Owners of Delftware

potteries Hendrick Marcellis van Gogh;

Lambert Ghysbrechtsz Kruyck; Aelbracht

Keyser.

B) Less succesful artists, living in houses

costing 800-1500 guilders

C) Artists and artisans not registered in

the Guild.

D) Apprentices and Journeymen.

(*Listed in Montias 1977, p. 104, Montias

1981, p. 193, Montias AA 1982, p. 134.)

Annual income of painters see Montias

'Estimates...' in Leidschrift 6 (1980) nr 3, p. 60.

Liedtke 2000, p. 122 states that Delft

dealers routinely sold paintings on behalf of Delft artists in other

cities - one could think of Renialme.

See Fabritius, nr 75; Vermeer nr 78 and De Hooch nr 80.

Illustration from the 'Meesterboek' in Ernst Günter Grime,

Jan Vermeer van Delft, DuMont Schauberg, Köln, 1974. p.

8.

Literature: The diary written in 1624 by David Beck mentions a visit to de Langue. See David Beck, Spiegel van mijn leven, een Haags dagboek uit 1624. Ingeleid en van aantekeningen voorzien door Sv. E. veldhuijzen, Hilversum 1993. Mentioned in Jeroen Blaak, Geletterde Levens, Hilversum, 2004.

For

more about the author of this home page click author.

For

more about the author of this home page click author.

Email me with suggestions (and sources) at kalden@xs4all.nl

More

Delft fine art and pottery has been put online on www.gemeentemusea-delft.nl

For online archival information on the Delft archive please click

www.archief.delft.nl

which offers one of the world's most advanced digital archival search

systems, made available free of cost. Enjoy!

More

Delft fine art and pottery has been put online on www.gemeentemusea-delft.nl

For online archival information on the Delft archive please click

www.archief.delft.nl

which offers one of the world's most advanced digital archival search

systems, made available free of cost. Enjoy!

Thanks to the Delft Archives Staff and the

Rijksmuseum Library Staff.

Research by Kaldenbach. A

full presentation is on view at www.xs4all.nl/~kalden/. When visiting Holland, join Private Art Tours.

Launched 16 February 2001; last update February 18, 2009.

In

the seventeenth century Dutch Republic major innovations in the art

of painting took place in various towns such as

Utrecht (a group of painters introducing

Caravaggio's chiaroscuro), in Rotterdam

(introducing genre painting, as in Willem Pietersz Buytewech's

(1591/92-1624) refined interior scenes with Merry Companies; also in

Leiden with Jan van Goyen (1596-1656)

opening up new avenues in landscape and in

Haarlem, where Frans Hals (1581/5-1666)

worked and in Amsterdam where Rembrandt

(1606-1669) developed new ways in portraiture and history

painting.

In

the seventeenth century Dutch Republic major innovations in the art

of painting took place in various towns such as

Utrecht (a group of painters introducing

Caravaggio's chiaroscuro), in Rotterdam

(introducing genre painting, as in Willem Pietersz Buytewech's

(1591/92-1624) refined interior scenes with Merry Companies; also in

Leiden with Jan van Goyen (1596-1656)

opening up new avenues in landscape and in

Haarlem, where Frans Hals (1581/5-1666)

worked and in Amsterdam where Rembrandt

(1606-1669) developed new ways in portraiture and history

painting. Traditionally

architecture painters depicted a (fantasy) church interior by

presenting a view along the axis of a church, the orthogonal

perspective lines all converging in one single vanishing point which,

according to the rules of the craft, had to be situated on the

horizon line in the far distance. It was normal for church interior

specialists to depict ornate and grand fantasy churches. This well

tested praxis in applying central perspective used since the Italian

Renaissance, was modified by Gerard Houckgeest who shifted his

painterly viewpoint away from the central axis

to one from the side aisle, at the same time presenting an an

actual part of the church in an oblique angle. As a draughtsman and a

painter this meant he first had to work out two diverging vantage

lines which both, one to the left and one to the right hand side,

should touch the horizon line. This more complicated technique

yielded views which looked surprisingly natural and were easy to

grasp for the common viewer. This innovation opened up surprising

avenues of artistic possibilities and shortly other Delft painters

caught on to this new way of presenting viewpoints within

perspective. These painters included the Delft born

Traditionally

architecture painters depicted a (fantasy) church interior by

presenting a view along the axis of a church, the orthogonal

perspective lines all converging in one single vanishing point which,

according to the rules of the craft, had to be situated on the

horizon line in the far distance. It was normal for church interior

specialists to depict ornate and grand fantasy churches. This well

tested praxis in applying central perspective used since the Italian

Renaissance, was modified by Gerard Houckgeest who shifted his

painterly viewpoint away from the central axis

to one from the side aisle, at the same time presenting an an

actual part of the church in an oblique angle. As a draughtsman and a

painter this meant he first had to work out two diverging vantage

lines which both, one to the left and one to the right hand side,

should touch the horizon line. This more complicated technique

yielded views which looked surprisingly natural and were easy to

grasp for the common viewer. This innovation opened up surprising

avenues of artistic possibilities and shortly other Delft painters

caught on to this new way of presenting viewpoints within

perspective. These painters included the Delft born  What

seems to have been characteristic of this group of Delft painters in

the 1650's was a common interest in the effects produced by lenses,

which were manufactured by pioneering scientists such as the local

What

seems to have been characteristic of this group of Delft painters in

the 1650's was a common interest in the effects produced by lenses,

which were manufactured by pioneering scientists such as the local

In

this atmosphere of artistic competition for new ways of depicting

life applying optimal illusionistic effects

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, see entries

In

this atmosphere of artistic competition for new ways of depicting

life applying optimal illusionistic effects

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675, see entries

In

the realm of defence we should not forget to mention a separate,

non-military but eqally essential organisation, the

In

the realm of defence we should not forget to mention a separate,

non-military but eqally essential organisation, the  Local

wealth was trumpeted by the brand new Delft

Local

wealth was trumpeted by the brand new Delft  The

interior of the

The

interior of the  Education

of a new generation of painters was of prime interest to the Guild.

For parents of a twelve or thirteen year old boy with an aptitude for

drawing it was a very costly undertaking to decide to pay for the

full six years of apprenticeship. During the lengthy painter's

training hardly any income was generated - as opposed to most other

kinds of trades during which the apprentice would immediately do

practical labour, producing goods, earning an income right away. But

a painter's education was a six years investment yielding a result

which was far from certain because of its artistic nature. A natural

aptitude of the trainee shown at the age of twelve or thirteen was no

guarantee for becoming a skilled and artistic craftsman.

Education

of a new generation of painters was of prime interest to the Guild.

For parents of a twelve or thirteen year old boy with an aptitude for

drawing it was a very costly undertaking to decide to pay for the

full six years of apprenticeship. During the lengthy painter's

training hardly any income was generated - as opposed to most other

kinds of trades during which the apprentice would immediately do

practical labour, producing goods, earning an income right away. But

a painter's education was a six years investment yielding a result

which was far from certain because of its artistic nature. A natural

aptitude of the trainee shown at the age of twelve or thirteen was no

guarantee for becoming a skilled and artistic craftsman.