Text as it was published in the art magazine Artibus et Histioriae, nr 6, 1982

written by dr. Arthur K. Wheelock, jr. and Kees Kaldenbach*

This article discusses archival finds regarding Johannes

Vermeer, 'View of Delft', oil on canvas, 96,5 x 115,7 cm. Copyright

Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague. Acquired

in 1822 as inv.no.92

This article discusses archival finds regarding Johannes

Vermeer, 'View of Delft', oil on canvas, 96,5 x 115,7 cm. Copyright

Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, The Hague. Acquired

in 1822 as inv.no.92

Vermeer's View of Delft is a glorious image of a city, so lifelike yet so hauntingly still and different that it never ceases to amaze the viewer. It is as though we are seeing the city on a Sunday morning before the activity of life overwhelms the quiet beauty of the setting.

The few people seen standing quietly talking on the near shore and those wandering on the quai on the opposite bank do not disturb the serenity of the scene .

Behind the city wall, sunlight, streaming in from the east, illuminates the gates and bridge, catching the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk and the orange tile roofs of the densely packed houses.

The

impact of this painting on a viewer seeing it for the first time is

perhaps best expressed by Thoré-Bürger in his article on

Vermeer, written in 1886. Thoré discovered View of Delft while

visiting the Mauritshuis and later wrote that its indelible image

motivated him to attempt a reconstruction of the oeuvre of this, to

him, totally unknown painter. He wrote: "In the museum of The

Hague, a superb, unique landscape stops visitors and keenly impresses

artists and connoisseurs of painting. It is aview of a town, with a

quai, an old portal, the buildings of a varied architecture, garden

walls, trees, and the foreground, a canal and a strip of land with

several small figures. The silver gray of the sky and the tones of

the water called to mind Philip Koninck. The burst of light, and

intensity of color, the solidity of impasto in certain areas, the

hyper-real yet very original effect also recalls something of

Rembrandt."

The

impact of this painting on a viewer seeing it for the first time is

perhaps best expressed by Thoré-Bürger in his article on

Vermeer, written in 1886. Thoré discovered View of Delft while

visiting the Mauritshuis and later wrote that its indelible image

motivated him to attempt a reconstruction of the oeuvre of this, to

him, totally unknown painter. He wrote: "In the museum of The

Hague, a superb, unique landscape stops visitors and keenly impresses

artists and connoisseurs of painting. It is aview of a town, with a

quai, an old portal, the buildings of a varied architecture, garden

walls, trees, and the foreground, a canal and a strip of land with

several small figures. The silver gray of the sky and the tones of

the water called to mind Philip Koninck. The burst of light, and

intensity of color, the solidity of impasto in certain areas, the

hyper-real yet very original effect also recalls something of

Rembrandt."

Thoré however, was not the first to notice View of Delft or to recognize its qualities. In 1822, when the painting was bought for the Mauritshuis, the sales catalogue described it as the most famous painting of this master, whose works seldom occur; the way of painting is the most audacious, powerful and masterly that one can image.

The intent of this article is to examine the nature of Vermeer's image, both to understand the manner in which he created such a naturalistic impression and how he has transformed a topographical view into one that is powerful and audacious in the way Thoré-Bürger and others have described. The audacious quality of the painting evolves from the bold silhouette of the city against the sky, the reflections of the buildings in the water; and above all, from the dramatic use of light to focus the composition and the article the space. The scene seem to bathed in light, yet in fact only the background buildings are directly illuminated by the sun. The dark clouds that cover and close the upper reaches of the sky effektivy shade the roofs and facades of the nearby buildings, water and foreground figures.

Vermeer's

painting represents the city of Delft as seen from the south. Beyond

the harbor that lies before the town stand the city walls that are

broken only by the small Kethel Gate, which is adjacent to the large

Schiedam Gate with its clock tower, the bridge, and its Rotterdam

Gate with its twin tower on the front gate. The site was an important

one for 17th-century Delft since from this area roads and waterways

extended to Rotterdam, Schiedam and Delfshaven.

Vermeer's

painting represents the city of Delft as seen from the south. Beyond

the harbor that lies before the town stand the city walls that are

broken only by the small Kethel Gate, which is adjacent to the large

Schiedam Gate with its clock tower, the bridge, and its Rotterdam

Gate with its twin tower on the front gate. The site was an important

one for 17th-century Delft since from this area roads and waterways

extended to Rotterdam, Schiedam and Delfshaven.

Maps from the period, including Bleaus Groundplan of Delft from 1649 and the large Figurative Map of Delft from 1675-78 show this harbor to be filled with boats not only lined up at the quai, but also sailing down the Schie.

For any of Vermeer's contemporaries, however, the nature of the View of Delft must have seemed particularly unusual. Although the location would have been immediately recognizable, the stillness of the scene would have been uncharacteristic. Even though Vermeer includes a large number of boats in this scene, only the small transport craft in the left foreground and the two larger herring ships moored at the shipyards at the right are immediately evident. The other boats are all moored alongside the fare edge of the water, where they visually blend with the background since Vermeer has rendered their colors and textures so similar to those of the adjacent quais, city walls and buildings. Clearly, Vermeer subordinated the commercial and mercantile activities of the area to focus on Delft's distinctive architectural character.

The

question remains as to whether Vermeer was as consciously selective

in his depictions of buildings he was in his representations of

shipping in the harbor. This work has generally been described as

being topographically accurate and many have speculated that he

created such an accurate image by using an optical device called

camera obscura. Indeed, close comparisons with old maps and town

plans convincingly reinforce the sensation that Vermeer had carefully

rendered the citys appearance from its southern side. Not only are

the distinctive gates and the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk identifiable,

but other elements as well. A wash drawing of a view along the quai

before the southern city wall by Jan de Bisschop presents one other

view of the Schiedam and Rotterdam Gates. This drawing also help us

to understand the complex shape of the Kethel Gate just to the left

of the Schiedam Gate that is accurately portrayed, although somewhat

indistinctly, in Vermeer's painting. From Vermeer's vantage point we

can see the façades of buildings lining the three canals that

branch out just beyond the bridge. These are evident to the left and

right of the Schiedam gate.

The

question remains as to whether Vermeer was as consciously selective

in his depictions of buildings he was in his representations of

shipping in the harbor. This work has generally been described as

being topographically accurate and many have speculated that he

created such an accurate image by using an optical device called

camera obscura. Indeed, close comparisons with old maps and town

plans convincingly reinforce the sensation that Vermeer had carefully

rendered the citys appearance from its southern side. Not only are

the distinctive gates and the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk identifiable,

but other elements as well. A wash drawing of a view along the quai

before the southern city wall by Jan de Bisschop presents one other

view of the Schiedam and Rotterdam Gates. This drawing also help us

to understand the complex shape of the Kethel Gate just to the left

of the Schiedam Gate that is accurately portrayed, although somewhat

indistinctly, in Vermeer's painting. From Vermeer's vantage point we

can see the façades of buildings lining the three canals that

branch out just beyond the bridge. These are evident to the left and

right of the Schiedam gate.

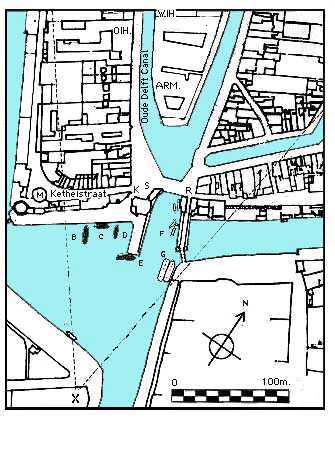

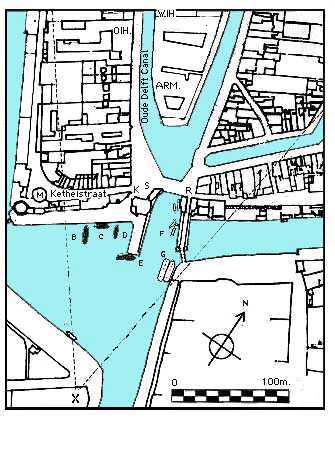

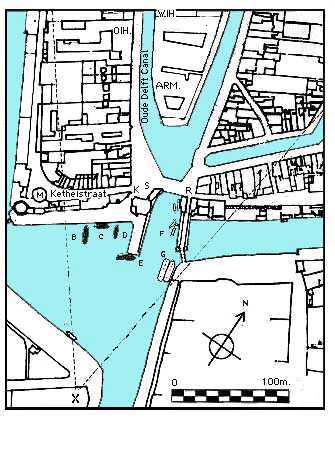

Drawing

by W.F. Weve after the Kadastrale Minuut of 1832. K=Kethel Gate;

S=Schiedam Gate; R=Rotterdam Gate. ARM=Armamentarium. OIH=East India

House. Ships represented by the letters A to G are described in

detail in the section on Shipping

in the View of Delft.

Drawing

by W.F. Weve after the Kadastrale Minuut of 1832. K=Kethel Gate;

S=Schiedam Gate; R=Rotterdam Gate. ARM=Armamentarium. OIH=East India

House. Ships represented by the letters A to G are described in

detail in the section on Shipping

in the View of Delft.

The façades of the buildings on the Kethelstraat just behind the city wall on the left, are accurate. A reconstruction of their appearance from a number of sources, including an old map called the Kadastrale Minuut (c.1830), a part of which was re-drawn recently by Mr.W.F. Weve for this study; these images correlate almost exactly with Vermeer's image. The distant multi-spired tower in the left center of the composition, which rises just beyond the dark cone-shaped spire, belongs to the Oude Kerk. All of the architectural elements seem to be accurately portrayed. Nevertheless, as will be discussed below, these same comparisons with old maps and town plans, as well as technical examinations of the painting itself, have revealed that Vermeer made a number of small adjustments in his depiction of the site to enhance its pictorial image.

The realism of the scene comes not only from the recognizable shapes of the structures but also from the truthfullness of their textures. One finds an extraordinary range of effects that capture the rough hewn character of the orange tile and blue slate roofs, stone, brick and mortar walls of buildings and bridges, leafy trees and wooden boats. Vermeer never precisely delineates these materials but devises a variety of means for suggesting their tactile characteristics. One of the most successful effects are the red tiled roofs along the left side of the painting. Here he has rendered the rough, broken quality of their surface by overlaying a thin reddish-brown layer with numerous small dabs of red, brown, and blue paint. These dots of paint are not blended into the underlying layer but are juxtaposed in such a way that their very irregularity helps suggest the roughness of the roof. Augmenting this effect is the manner in which Vermeer enhanced the grainy quality of the tile roof with small bumps which protrude from the surface. These bumps are large particles of lead white paint that Vermeer either applied to the ground in this area or mixed with the thin reddish layer that established the base color for the roof.

These effects are quite different from those seen in the sunlit roofs where he has minimized individual nuances of the tile. Here one sees a relatively uniform surface, although Vermeer has emphasized the physical presence of the tiles by using a thick bumpy layer of salmon-colored paint. The impastos of these sunlit roofs are even more strikingly evident in the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk. Vermeer has almost sculpted the sunlit portions of the tower with a heavy application of lumpy lead tin yellow paint. The blue roof of the Rotterdam Gate is relatively smooth, with white highlights dotting the surface to enliven it. The chimneys, however, are rendered in a technique similar to that used on the red roofs on the left, including the lumps of lead white that protrude through the reddish layer.

Visible

upon close examination is the fact that Vermeer changed his mind

about the color of the yellow roof above the Rotterdam Gate ; he

painted a dense yellow layer, similar in texture to that of the

Nieuwe Kerk, over the salmon color used in the distant roof tops. His

painting technique differs again in the boat depicted in the lower

right; here Vermeer painted highlights that do not suggest texture.

Indeed, the diffuse highlights often obscure the underlying structure

rather than reinforce it. They seem intended to suggest flickering

reflections from the water onto the boat. Painted in a variety of

ochers, grays and whites, these highlights cover a layer area and

have a more regular contour than the dots we observed on the red tile

roofs. Over these diffuse highlights Vermeer painted more opaque

ones, some of which were apparently applied wet in wet.

Visible

upon close examination is the fact that Vermeer changed his mind

about the color of the yellow roof above the Rotterdam Gate ; he

painted a dense yellow layer, similar in texture to that of the

Nieuwe Kerk, over the salmon color used in the distant roof tops. His

painting technique differs again in the boat depicted in the lower

right; here Vermeer painted highlights that do not suggest texture.

Indeed, the diffuse highlights often obscure the underlying structure

rather than reinforce it. They seem intended to suggest flickering

reflections from the water onto the boat. Painted in a variety of

ochers, grays and whites, these highlights cover a layer area and

have a more regular contour than the dots we observed on the red tile

roofs. Over these diffuse highlights Vermeer painted more opaque

ones, some of which were apparently applied wet in wet.

Vermeer's interest in implying textures and effects of light by actually varying the painting technique underscores his intent on making images as realistic as possible.

Nevertheless, certain techniques of painting, compositional distortions and alterations in topography indicate that Vermeer was not primarily concerned with imitating reality (like the artists who produced profiles), but with transforming it into an image that was effective as a work of art.

As has been mentioned, Vermeer, in giving dramatic impact to his work, emphasized the city's silhouette against the light sky. He not only darkened the foreground buildings but accentuated their contours using a purely artificial devicea white line in the sky that can be seen just above many of the roofs, most clearly above the Schiedam Gate. In the center distance Vermeer has tied together the diverse roof lines with a pale blue horizontal shape that is meant to read as a roof, but which has no relationship to the reality of the situation. The long, horizontal building on the left of the painting is almost certainly an imaginative construction; no comparable structure is found in the contemporary city.

In all of these changes, Vermeer sought to simplify the cityscape by emphasizing the parallel nature of the buildings orientation. If one compares the site with a section of the large Figurative Map of Delft that was executed in the mid-1670s, one sees that the topography is more irregular than Vermeer suggests.

Josua

de Grave, two images, 1695, in Album Rademaker, Municipal

Archives, Delft. G1=Rotterdam Gate; G2=Front part of R.G.;

G3=Schiedam Gate; G4=Kethel Gate.

The twin towers of the Rotterdam Gate, for example, project far out into the water. The extent to which they project can clearly be seen in two drawings by Josua de Grave in which the gate is seen from a location to the far right of Vermeer's painting. Vermeer flattened the angle of the Gate by distorting the perspective. The building is virtually at right angles to the picture plane and, to be consistent with the rest of the composition, he should have drawn the focal point of the perspective so that it would fall slightly left of center. Orthogonals constructed along the Gate, however, join far to the left of the painting, meaning that Vermeer must have consciously flattened their forms.

A

pen drawing of the same site from the early 18th century by the

topographical artist Abraham Rademaker offers an interesting

comparison. Although Rademaker's vantage point is slightly closer and

lower than Vermeer's, his view in other respects is comparable. His

interpretation of the scene, however, is different. In his drawing

the covered portion of the Rotterdam Gate projects forward, therby

creating a more three-dimensional composition. Part of this effect

comes from the perspective, part from the detailed articulation of

architectural elements, and part from the effect of shadows on these

buildings. Rademaker, like many other artists who depicted this area,

emphasized the horizontal bands on the side of the Rotterdam Gate

that were made by alternating levels of brick and light-colored

natural stone, whereas Vermeer merely suggested their presence with a

series of shifting light colored dots of paint. Interestingly,

examination of the painting with x-radiography and infra-red

reflectography has shown that Vermeer initially painted the twin

towers of the Rotterdam Gate in bright sunlight.

A

pen drawing of the same site from the early 18th century by the

topographical artist Abraham Rademaker offers an interesting

comparison. Although Rademaker's vantage point is slightly closer and

lower than Vermeer's, his view in other respects is comparable. His

interpretation of the scene, however, is different. In his drawing

the covered portion of the Rotterdam Gate projects forward, therby

creating a more three-dimensional composition. Part of this effect

comes from the perspective, part from the detailed articulation of

architectural elements, and part from the effect of shadows on these

buildings. Rademaker, like many other artists who depicted this area,

emphasized the horizontal bands on the side of the Rotterdam Gate

that were made by alternating levels of brick and light-colored

natural stone, whereas Vermeer merely suggested their presence with a

series of shifting light colored dots of paint. Interestingly,

examination of the painting with x-radiography and infra-red

reflectography has shown that Vermeer initially painted the twin

towers of the Rotterdam Gate in bright sunlight.

In his original conception the pronouced light and shadow effects on the towers were comparable to those seen in Rademakers drawing.

Comparison of View of Delft with Rademakers drawing illustrates other differences; In the latter, the profile of the city is more jagged and uneven and buildings are taller, narrower and set more closely together. A mid-eighteenth century and print after a drawing by Cornelis Pronk shows similar characteristics.

Vermeer made numerous modifications in his city view to simplify and harmonize its appearance. To emphasize the horizontals of the cityscape, he apparently straightened the bowed arch of the bridge. One may compare, for example, the bridge in Vermeer's painting to a drawing by Josua de Grave, 1695, showing the bridge from the inside of the city. It is uncertain whether Vermeer also elongated the bridge as well. Most views of the city from the south place the two gates somewhat closer together than Vermeer does. Some artists, however, wanted to show more buildings within their frames and compressed the scene. All topographical views of this scene vary slightly, however, and no single view can be relied upon for its accuracy. Even such a precise and detailed drawing as that by Gerrit Toorenburgh (1737-1785) seems to be wrong in the position of the Nieuwe Kerk.

When a structure such as the armament warehouse, the large building behind and to the left of the Schiedam Gate, had a very complex roof shape, Vermeer minimized its complexity by eliminating orthogonals that would suggest recession in space and by coloring it uniformly. An x-ray of this area demonstrates that he arrived at this solution only after blocking out the roofs in a much more three-dimensional fashion. As with the Rotterdam Gate, he had initially accented portions of the roof by painting these in strong sunlight.

Finally

the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk, while strikingly illuminated, is not as

physically large as one might expect, its height and width varying

greatly in the views of various artists. For example, in a rather

picturesque view by Jan de Beyer (1703-1780), from 1750, the tower is

extremely high. Nevertheless, specific measurements of the

proportions of the existing building in comparison to the painting

suggest that the tower should be either less wide, or higher in

Vermeer's work to be totally accurate. Although the spire burned down

in 1872, and was replaced with a somewhat taller neo-gothic one, the

size of the base remained the same and accurate calculations based on

contemporary photographs of the site can be made. Vermeer may have

minimized the scale on the Nieuwe Kerk to emphasize its distance from

the foreground plane. It also blends more successfully with the

horizontality of the composition than it would were it slightly

larger.

Finally

the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk, while strikingly illuminated, is not as

physically large as one might expect, its height and width varying

greatly in the views of various artists. For example, in a rather

picturesque view by Jan de Beyer (1703-1780), from 1750, the tower is

extremely high. Nevertheless, specific measurements of the

proportions of the existing building in comparison to the painting

suggest that the tower should be either less wide, or higher in

Vermeer's work to be totally accurate. Although the spire burned down

in 1872, and was replaced with a somewhat taller neo-gothic one, the

size of the base remained the same and accurate calculations based on

contemporary photographs of the site can be made. Vermeer may have

minimized the scale on the Nieuwe Kerk to emphasize its distance from

the foreground plane. It also blends more successfully with the

horizontality of the composition than it would were it slightly

larger.

Aside from topographical changes in light effects, Vermeer made a number of adjustments in the boats and reflections in the water that further enhances the strong horizontal orientation of the scene. Infra-red reflectography reveals that Vermeer made a fascinating alteration in the position of the herring boats on the far right of the composition. He originally painted both boats somewhat smaller; he enlarged the stern of the foreground boat and the bow of the second. The most significant change is with the fore ground boat which once ended just before the front face of the Rotterdam Gate. The original reflection in the water of this first idea can be seen in the reflectogram. By extending the rear of this boat backwards and to the left, Vermeer minimized its recession into space as he had by altering the perspective of the Rotterdam Gate.

A

further important change in the composition, visible in x-rays and

infra-red reflectography, was the adjustment of the reflection of the

twin towers of the Rotterdam Gate. The original reflections denoted

the architectural forms of the building on the far shore quite

precisely. In this final design, however, Vermeer extended them

downward so that they intersect with the bottom edge of the picture.

The effect of the combined reflection of the Rotterdam Gate towers

and the Schiedam Gate in the center (both of which reach the

foreground shore) is to bind the city profile and foreground elements

in a subtle yet essential manner. The reflections, which function

almost as shadows, give added weight and solemnity to the mass of

buildings along the far shore. Moreover, beyond anchoring these

structures in the foreground, the exaggerated reflections of specific

portions of the city profile create accents that establish a

secondary visual pattern of horizontals, verticals and diagonals

across the scene.

A

further important change in the composition, visible in x-rays and

infra-red reflectography, was the adjustment of the reflection of the

twin towers of the Rotterdam Gate. The original reflections denoted

the architectural forms of the building on the far shore quite

precisely. In this final design, however, Vermeer extended them

downward so that they intersect with the bottom edge of the picture.

The effect of the combined reflection of the Rotterdam Gate towers

and the Schiedam Gate in the center (both of which reach the

foreground shore) is to bind the city profile and foreground elements

in a subtle yet essential manner. The reflections, which function

almost as shadows, give added weight and solemnity to the mass of

buildings along the far shore. Moreover, beyond anchoring these

structures in the foreground, the exaggerated reflections of specific

portions of the city profile create accents that establish a

secondary visual pattern of horizontals, verticals and diagonals

across the scene.

Such modifications in topography and intentional compositional adjustments thus force us to reconsider the assumptions that we bring to this work. If the view of Delft does indeed vary slightly from topographical exactitude, how are we to approach the question of Vermeer's use of the camera obscura? Although the assumption has often been made that Vermeer used the camera obscura to create a topographically accurate image, such clearly was not the case. In a broarder sense, however, he might have viewed the image produced by the camera obscura as a means of enhancing the illusion of reality in his painting.

As has been noted in the literature, Vermeer could have seen such a view of Delft from the second story of a house situated across the harbor from the Schiedam and Rotterdam gates. Such a house can actually be seen on old maps, and recent scientific projections of his viewpoint have reinforced that hypothesis. Of course, no documentary evidence indicates whether or not Vermeer actually set up a camera obscura in this location or even he painted his scene there. Nevertheless, the hypothesis that Vermeer used the camera obscura at some stage in his working process gains validity because of the distinctive effects of light, color, atmosphere and diffusion of highlights along the far shore.

Camera obscura were widely acclaimed in the 17th century the naturalistic landscape effects that they created. A measure of their effectiveness comes from the fact that they present a living image, where movements of clouds, water and birds are visible; the apparent realism, however, is also delivered from the vividness of the image. Colors accents and contrasts of light and dark are intensified and apparently exaggerated through the use of a camera obscura, thus giving an added intensity to the image. This phenomenon has the subsidiary property of minimizing effects of atmospheric perspective. In the View of Delft , all of these phenomena are present. Contrasts of light and dark are pronounced, colors are vivid and atmospheric perspective is negligible.

Along the far shore of the Schie, particularly on the boat, numerous diffused highlights appear that compare closely to those seen in unfocused images of a camera obscura. Vermeer, from almost the beginning of his career,articulated his images with small dabs or globules of paint to enhance textural effects. The diffused highlights on the boat, however, are different in View of Delft than they are in his other works from the late 1650s and early 1660s, with the possible exception of The Milkmaid in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Not only are they more diffuse than in other paintings, they are unrelated to texture.

Their purpose is to suggest flickering reflections off the water. Such reflections would appear as diffuse circular highlights in an unfocused image of a camera obscura, and would appear only in sunlight, not in the shadows as they are here painted. Thus, even when it seems that he used such a device, Vermeer modified and adjusted its image for compositional reasons.

Vermeer apparently responded to such visual stimulate from a camera obscura and recognized that the optical effects reinforced both the naturalistic and expressive characteristics he was seeking. His realism is thus of a most profound type. While he has sought to translate the rich varieties of shape, materials and textures of the physical world through his painting techniques, he has also given these objects an aura and significance beyond the limited confines of time and place.

The View of Delft is unique in Vermeer's oeuvre. Although The Little Street in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam also depicts an exterior scene of buildings, it is a far more intimate work than this large and imposing picture. The View of Delft is also, as far as is known, the earliest view of the city from this vantage point. We must address the issue, then, of how it came to be painted. We have no record of a commission and, indeed, no mention of the paintings existence prior to 1696, the year that it appeared in an Amsterdam sale as De Stad Delft in perspectief, te sien van de Zuyd-zy, door J. vander Meer van Delft. It is likely that the painting, as well as most of the twenty others by Vermeer that appeared in this sale belonged to the bookprinter Jacob Abrahams. Dissius. An 1682 inventory of his collection contained no fewer than nineteen paintings by Vermeer, although, unfortunately, none were specifically identified. Whether or not Dissius purchased these directly from Vermeer during his lifetime or from Vermeer's widow or mother-in-law sometime after his death in1675 is unknown. In any event, no evidence suggests that the painting was executed on commission from the St. Lukes Guild or any other civic body.

[Author's note made in 2001: research by Montias has since shown that Vermeer's mecenas was Pieter Claesz van Ruijven (1624-1674) and his wife Maria de Knuijt (16xx-1681) ; they married 1653 and were independently wealthy.]

Lacking specific evidence of commission and with the distinct possibility that the View of Delft remained in Vermeer's possession throughout his life, one hesitates to speculate on Vermeer's motivation for paintings this work; nevertheless, certain observations may be offered. In the broadest sense, Vermeer chose a format that was familiar through cartographic traditions - a profile view of a city was often found accompanying its larger ground plan. Such a profile is found, for example, on the large Figurative Map of Delft. These profile views of cities, however, generally emphasized the citys most distinctive landmarks. In the case of Delft, that vantage point is from the west where the towers of both the Oude Kerk and Nieuwe Kerk dominate the city's profile. Vermeer's view in this respect is uncharacteristic of topographic tradition since it does not sufficiently highlight these distinctive monuments of the city. In his painting the tower of the Oude Kerk can barely be discerned in the distant left center of the composition.

Painted

city views occur only sporadically throughout the first half of the

seventeenth century. Although a certain number of topographical views

were painted early in the century, among which are two scenes of

Delft by Hendrick Vroom, specific

town portraits are found only frequently by midcentury. In the early

1650s, however, artists in Delft began to focus on the major

architectural monuments of the city, in particular the Oude Kerk and

the Nieuwe Kerk. A dynamic school of architectural painting emerged

as Gerard Houckgeest, Emanuel

de Witte, and Hendrick van

Vliet depicted a wide range of interior views of these vast

spaces. Also during the 1650s the city itself became an important

backdrop for portraits (Jan

Steen, The Burgher of Delft and His Daughter, private

collection, Great Britain) and genre scenes (Carel Fabritius,

View of Delft with a Musical Instrument Sellers Stall,

National Gallery, London; Pieter de

Hooch, A Dutch Courtyard, National Gallery of Art,

Washington, D.C.). Vermeer's Little

Street is an important work in this tradition, even though no

recognizable monuments are depicted, because for the first time

figures are totally subordinate to the quiet beauty of the

architectural forms and their textures.

Painted

city views occur only sporadically throughout the first half of the

seventeenth century. Although a certain number of topographical views

were painted early in the century, among which are two scenes of

Delft by Hendrick Vroom, specific

town portraits are found only frequently by midcentury. In the early

1650s, however, artists in Delft began to focus on the major

architectural monuments of the city, in particular the Oude Kerk and

the Nieuwe Kerk. A dynamic school of architectural painting emerged

as Gerard Houckgeest, Emanuel

de Witte, and Hendrick van

Vliet depicted a wide range of interior views of these vast

spaces. Also during the 1650s the city itself became an important

backdrop for portraits (Jan

Steen, The Burgher of Delft and His Daughter, private

collection, Great Britain) and genre scenes (Carel Fabritius,

View of Delft with a Musical Instrument Sellers Stall,

National Gallery, London; Pieter de

Hooch, A Dutch Courtyard, National Gallery of Art,

Washington, D.C.). Vermeer's Little

Street is an important work in this tradition, even though no

recognizable monuments are depicted, because for the first time

figures are totally subordinate to the quiet beauty of the

architectural forms and their textures.

On October 12, 1654, a disaster occurred in Delft that had important consequences for the evolution of Delft architectural painting. On that date the gunpowder warehouse in Delft exploded, devastating a large, northeastern section of the town and killing many citizens, including the painter Carel Fabritius. The explosion and its aftermath became the subject of many city views by Delft artists, particularly Daniel Vosmaer and Egbert van der Poel. Although these pictures have an anecdotal character, the paintings generally included a panoramic view of the city. including the two vast towers of the Nieuwe Kerk and Oude Kerk.

Rather than a description of the aftermath of a disaster, Vermeer's View of Delft has a totally different character. Almost as a reaction to the depictions of the effects of the explosion on Delft, he chose a site where evidence of the destruction could be seen. As with the architectural paintings of the early 1600s, his is the celebration of a citys existence; a reminder, through its careful recording of massive gates, walls and church spires, of Delfts old and distinguished history. The Rotterdam and Schiedam gates, which date to the fourteenth century, had served to control the traffic over land and water, and to defend the city against enemy attack. After the assassination of Willem the Silent in 1584 in Delft and the departure of the Court and the seat of government to The Hague, the threat of military attack lessened. The Schiedam Gate, which once had twin towers like those in the Rotterdam Gate, was altered in 1590-91 and the harbor dug in 1614. The Rotterdam Gate remained intact (with the exception of some aesthetic modifications on the city side) until its twin towers were demolished sometime after 1695 (See the appendix).

Beyond these shadowed walls and gates, light floods the city. It strikes in particular the Nieuwe Kerk, the massive fifteenth century gothic structure that stands at one end of the citys market square. The church was, in fact, the central focus of civic life and held additional importance as it housed one of the most famous monuments in the Netherlands, the Tomb of Willem the Silent. Whether or not Vermeer's topographical adjustments were symbolically as well as compositionally motivated are difficult to determined. Nevertheless, Vermeer's image of the city is almost reverential in character. From this viewpoint Delft remains distant and remote, the water obstructing our direct approach to the far shore. The strong horizontal and vertical emphasis and somber lightening of the foreground elements creates a church and inner city lends a radiance that draws one to it.

The likelihood that Vermeer consciously sought to give a special aura to his view of Delft is reinforced when one notes the contemporary interest in Delft for glorifying the city, its sovereignty and its arts. In 1661, the newly refurbished St. Lukes Guild commissioned various artists, including Cornelis de Man and Leonaert Bramer to execute allegorical works on the art of painting, architecture and sculpture. Bramer also painted a series of the Liberal Arts with Painting explicitly added to the original seven. In 1667 upon the publication of Dirk van Bleyswijck's Beschryvinge der Stadt Delft, a description and history of the city he chose for his title page design an allegorical figure of Fame blowing upon her gilded trumpets. A few years later the town government commissioned the large Figurative Map of Delft. In this detailed view of the town, Delft was shown in its full glory, commanding the surrounding region. The symbolism of Delfts importance, however, lay not totally in the impressive scale of the map that hung in the Burgomasters room in the city hall. When Bleyswijck expanded upon his book and described the large Figurative Map of Delft, he focused not on the map but on the emblematic symbols contained in the frame that surrounded it.

Such

literary associations are certainly different in kind from the more

subjective devices used by Vermeer to glorify Delft and its heritage,

but they have at their roots a common basis. This foundation, that

art is more than descriptive, that it contains references to

essential truths fundamental to human experiences, is one that is

found manifested in most of Vermeer's paintings. In this, the most

moving of all his masterpieces, references to emblematic meanings,

have been eliminated in favor of a far more profound expression of

human endeavor that he has achieved through a selected transformation

of naturals forms.

Such

literary associations are certainly different in kind from the more

subjective devices used by Vermeer to glorify Delft and its heritage,

but they have at their roots a common basis. This foundation, that

art is more than descriptive, that it contains references to

essential truths fundamental to human experiences, is one that is

found manifested in most of Vermeer's paintings. In this, the most

moving of all his masterpieces, references to emblematic meanings,

have been eliminated in favor of a far more profound expression of

human endeavor that he has achieved through a selected transformation

of naturals forms.

APPENDIX

The following constitute concise histories of the primary architectural elements depicted in Vermeer's View of Delft.

The

Rotterdam Gate, a caste-like type of city gate, was built in the

14th century. During the reconstruction of

1590-91, the facade on the town side was, according to modern

aesthetical demands, ornately decorated. The entire structure

consists of two sections, the main gate building and the front gate,

with two octagonal hanging towers flanking the drawbridge. This front

entrance was controlled by watchman from a room directly above the

drawbridge. The outer wall shows signs of repair done with yellow

brick.

The

Rotterdam Gate, a caste-like type of city gate, was built in the

14th century. During the reconstruction of

1590-91, the facade on the town side was, according to modern

aesthetical demands, ornately decorated. The entire structure

consists of two sections, the main gate building and the front gate,

with two octagonal hanging towers flanking the drawbridge. This front

entrance was controlled by watchman from a room directly above the

drawbridge. The outer wall shows signs of repair done with yellow

brick.

The road from the drawbridge through the main gate is flanked by covered corridors about three meters high, built on arches. Above the main gate watchmen control the traffic through openings in the floor. In order to seal the entrance, a portcullis could be lowered at the town facade.

The

main gate probably was symmetrical in floor plan and roof, but the

first trustworthy map of c. 1830 shows an asymmetrical design. This

front gate remained intact longer than its neighbors, until some time

after 1695. In that year, Josua de Grave made a series of drawings

from different angles, possibly with the planned demotion, in mind.

At the demolition, the foundation remained to serve as a road. Due to

necessity, the single drawbridge was replaced with a larger one in

1737, and the main gate was demolished in 1834 to make way for the

construction of an avenue.

The

main gate probably was symmetrical in floor plan and roof, but the

first trustworthy map of c. 1830 shows an asymmetrical design. This

front gate remained intact longer than its neighbors, until some time

after 1695. In that year, Josua de Grave made a series of drawings

from different angles, possibly with the planned demotion, in mind.

At the demolition, the foundation remained to serve as a road. Due to

necessity, the single drawbridge was replaced with a larger one in

1737, and the main gate was demolished in 1834 to make way for the

construction of an avenue.

The gate was built of common brick alternated, for aesthetic reasons, with layers of light colored natural stone on the façade which produced a horizontal character and defend space. These layers were sometimes painted to enhance their appearance. The number of layers varies greatly inthe depictions by other artists, but seventeen would be an educated guess. The roof has a cross-shaped summit, and a hiproof with pairs of dormer windows on the four triangular sides. On the viewers side of the gate the sloping roof of the North-South axis continues down the sides of the building where the chimneys rise. A pierced contour is created by the pointed wrought-iron and lead ornaments on the roof top and on the

chimneys. The S-shaped stone ornaments on the façade and on the base of the chimneys create great difficulties for artists; many different versions can be seen.

The Schiedam Gate and the Rotterdam Gate are, broadly speaking, twin structures. The corridor between the main building of the Schiedam Gate and the front had collapsed by the end of the 16th century. In 1590-91 this front gate was demolished, while its foundation remained as a pier. The main gate was lowered and modernized with stepped gables on four sides. To serve the ferries, a clock and bell tower were installed.

From Vermeer's point of view, the building seems rectangular but in fact is diamond shaped. Attached to the left side of the gate is an irregular structure; its precise shape can be studied in Abraham Rademakers drawing.

The layers of natural stone in the facade are fewer in number than those on the Rotterdam Gate. Two pairs of two bands are evident with an added horizontal band just above the arched entrance way. Vermeer included the holes in which the scaffolding rested. These can also be seen in Gerrit Toorenburghs careful rendering of the site in his 18th century drawing.

On the left side of the City Wall, Vermeer added a horizontal (stone?) band in the center. No other artist shows this band; it does not even appear in Bisschops more detailed rendering . Towards the right, the wall is at an angle and leads into the small Kethel Gate, which was built after 1591 for easier access to the quay and the bridge. On depictions by other artists we see two doors covered by a simple sloping roof. On the town side, a decoration in classical style was constructed, crowned by a lion holding the Delft coat-of-arms. The wall on the town side was reinforced by a mount of earth; some structures occupy this space, including a mill and some sheds.

The

Harbor is actually a canalized watercourse, referred to as the kolk.

Around the 14th century the Rotterdam and Schiedam Gate were built as

(almost) symmetrical twin towers in the banks of the Schie. They

served to control the traffic over water and land, and to defend the

city at a point where enemy attack was expected. At the end of the

16th century the status of Delft as a military stronghold had

declined. By that time, the front gate of the Schiedam was already

ruin, and in 1590-91, extensive renovations were carried out. The

front gate of the Schiedam Gate was demolished and its main building

lowered and modernized. A triangular rampart was constructed at the

front of the gate, though by 1614 a harbor was needed more urgently

than the rampart, which was dug away. Thus on the Delft end of the

Schie a triangular harbor was created with a small pier (the Hoofd)

extending from it for additional docking space for the ferry and

transportation service.

The

Harbor is actually a canalized watercourse, referred to as the kolk.

Around the 14th century the Rotterdam and Schiedam Gate were built as

(almost) symmetrical twin towers in the banks of the Schie. They

served to control the traffic over water and land, and to defend the

city at a point where enemy attack was expected. At the end of the

16th century the status of Delft as a military stronghold had

declined. By that time, the front gate of the Schiedam was already

ruin, and in 1590-91, extensive renovations were carried out. The

front gate of the Schiedam Gate was demolished and its main building

lowered and modernized. A triangular rampart was constructed at the

front of the gate, though by 1614 a harbor was needed more urgently

than the rampart, which was dug away. Thus on the Delft end of the

Schie a triangular harbor was created with a small pier (the Hoofd)

extending from it for additional docking space for the ferry and

transportation service.

The Rotterdam and Schiedam Gates were demolished in the years 1834 and 1836, just at the time when photography was invented; however, no photograph is known of these gates. Owing to their southern, sunlit position, and their picturesque situation on the water, the gates have been drawn, painted, etched and en graved many times. Most of this material may be found in the Municipal Archives and the Stedelijk Museum "Het Prinsenhof". Thirty of these renderings show the gates frontally, from about the position Vermeer chose. For this study views from other angles have also been traced. Together they total forty-five drawings and watercolors, seventeen prints, eleven city maps and four paintings, excluding the copies mentioned in Blankert. We wish to thank the staff of the Municipal Archives for their cooperation. In the Stedelijk Museum "Het Prinsenhof" Ineke Spaander has been particularly helpful for this research.

Tip

In the section on 'Walking with Vermeer' you may actually walk towards and into the Rotterdam gate and stroll about. Click Johannes Vermeer in the yellow menu.

Literature

Extremely important information on the history of Delft and its cultural heritage can also be found in the many essays contained in the sequence of the following exhibition catalogues from the Stedelijk Museum 'Het Prinsenhof', Delft.

De Stad Delft, cultuur en maatschappij tot 1572 (part I), Delft, 1978.

De Stad Delft, cultuur en maatschappij van 1572 tot 1667 (part II) Delft, 1981.

De Stad Delft, cultuur en maatschappij van 1667 tot 1813 (part III) Delft, 1982.

*The detailed notes are not included in this internet version. In 2001 the text was scanned and uploaded by Kees Kaldenbach; some minor errors in the original text were corrected and one commentary on the provenance was added. C.J. Kaldenbach.

For

more about the author of this home page click author.

You will stay within this Vermeer home page.

For

more about the author of this home page click author.

You will stay within this Vermeer home page.

Email me at kalden@xs4all.nl

Launched on internet March 1, 2001. Updated Nov 14, 2014.

2013: BBC shoot in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

BBC 4 TV programme shoot in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, March 28, 2013 just before the formal opening. Kaldenbach in red jacket. Behind the middle cameraman interviewer Andrew Graham-Dixon. The director approaching from the right.

In the middle: daughter Suzanne, who has not been there for 12 years, Kees Kaldenbach and interviewer Andrew Graham-Dixon.

Research presented in November 2014 about the Amsterdam art collector Mannheimer: he almost bought the best Vermeer: The Art of Painting (now in Vienna).

Updated June 9, 2016. Updated 27 October 2016.