Childbirths,

midwives, obstetricians

Childbirths,

midwives, obstetricians Childbirths,

midwives, obstetricians

Childbirths,

midwives, obstetriciansNew finding: v@ginal massage as an actual and regular historical medical practice (see middle under).

Johannes Vermeer and his wife Catherina Bolnes married in 1653 when both were quite young. On the wedding day he was 20 years old and she 21. In the course of their 22 years of marriage, which lasted until Johannes' death in December 1675, she became pregnant no less than fifteen times, which is an exceptionally high number. Eleven children were alive in the spring of 1676. In the Thins/Bolnes/Vermeer house traditions and rituals around pregnancy and childbirth must have played a considerable role.

In april 1632, Beatrix Gerrits applied for the position as "town midwife" in the town of Gorinchem. She was second wife of Master Reynier Balthens (Johannes Vermeer's uncle) Montias Vermeer and his Milieu, 1989, p. 88.

The following text gives an impression of traditions and customs surrounding pregnancy and birth. The historical role of midwives, who were the foremost professional group among women in Dutch society, is also discussed.

Midwives'

tasks

Midwives'

tasksAccording to regulations midwives were allowed to attend to only one childbirth at the time, and once the birth was on its way she was not allowed to leave the scene for another childbirth. Pregnant women therefore booked the services of a midwife well in advance of the calculated birth date.

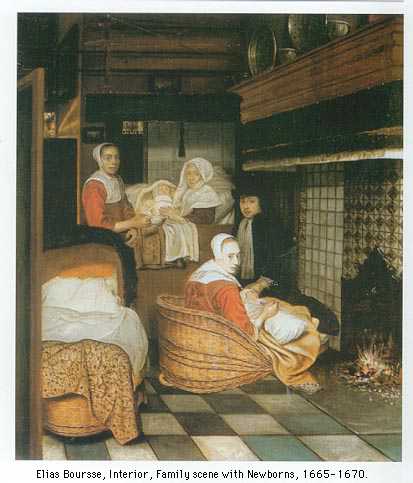

When the labour had begun, somebody close by (a husband, neighbor, maid or servant) was to run for the midwife. She was obliged to come at that moment. The house was prepared for childbirth by neighbors, family or by personnel. One had to gather the fire basket, the cradle, the diapers and the bed (Source: Van der Borg, p. 30). Normally the husband was not present at childbirth (Carasso 1987, p. 20).

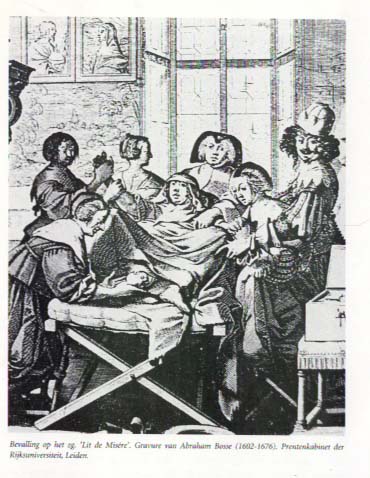

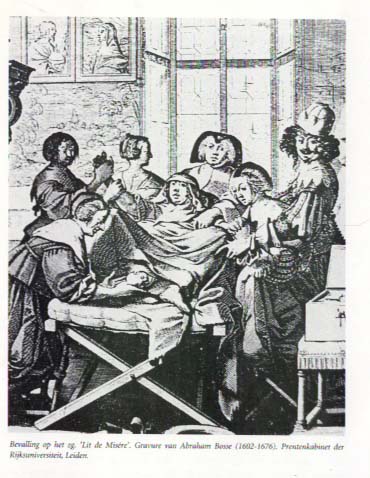

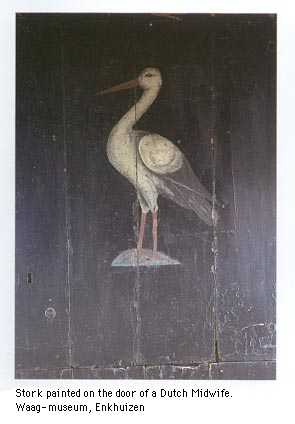

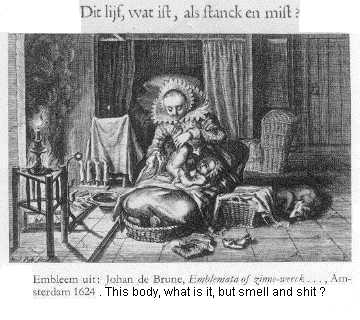

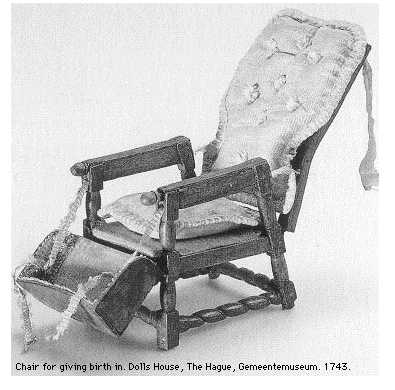

During the delivery the woman sat either on a delivery chair, or on a mattress in the bedstead. However, as the bedstead was closed off on three sides this was not very convenient for bystanders. A free standing bed could be made by aligning a number of chairs, their backs towards the floor, on which a mattress was laid. This temporary contraption was called a short bed (Dutch: 'kortbed') Sometimes the woman in labour sat on the lap of another woman, the lap-woman (Dutch: 'schootster' ; Van der Borg, p. 31).

The

midwife or her male counterpart, the accoucheur stood, kneeled or sat

between the legs of the woman giving birth. Both of her legs were held wide

by other women who were giving assistance. The skirts were pulled high in order

to keep them from getting dirty from the various seeping fluids. Generally,

rooms were not well heated in the Dutch republic. In order to keep the

mother from getting cold, a blanket was laid on her lap and over her legs. The

midwife guided the birth and when necessary she did her manual work to further

the birth. At the moment of birth she caught the newborn and cut the umbilical

cord. Then she laid the child in cloths and gave it to the by-standers who checked

both baby and umbilical cord for possible problems. Finally the child took care

of extracting the complete placenta which was also checked by the by-standers.

Then the mother was taken care of and put to bed. The baby was taken care of

near the fire basket, swaddled in cloth and

handed to the baby's father, who handed a traditional money tip to the midwife.

The other bystanders then cooked a special dinner. (Van

der Borg, p. 31).

The

midwife or her male counterpart, the accoucheur stood, kneeled or sat

between the legs of the woman giving birth. Both of her legs were held wide

by other women who were giving assistance. The skirts were pulled high in order

to keep them from getting dirty from the various seeping fluids. Generally,

rooms were not well heated in the Dutch republic. In order to keep the

mother from getting cold, a blanket was laid on her lap and over her legs. The

midwife guided the birth and when necessary she did her manual work to further

the birth. At the moment of birth she caught the newborn and cut the umbilical

cord. Then she laid the child in cloths and gave it to the by-standers who checked

both baby and umbilical cord for possible problems. Finally the child took care

of extracting the complete placenta which was also checked by the by-standers.

Then the mother was taken care of and put to bed. The baby was taken care of

near the fire basket, swaddled in cloth and

handed to the baby's father, who handed a traditional money tip to the midwife.

The other bystanders then cooked a special dinner. (Van

der Borg, p. 31).

Among the necessities were baby-gear and pregnancy clothes. For a delivery one furthermore needed a fire basket, a cradle, diapers, a tub, a place to sit or lie down, two foot stoves ; cloths, grease and possibly a folding screen. The midwife also brought a number of items with her: a pair of scissors; materials to tie the umbilical cord; soothing oils, a catheter, an enema syringe. Those were her professional tools. But her psychology, character and comportment were also quite important on such a life threatening time for both mother and child. As her best possible traits of personality she brought strength of character and an outer air of calmness. If and when the birth went wrong, she gave words of consolation in the great misery and afterwards offered emotional rescue. Statistics gave reasons to worry: from each group of 1000 women giving birth 14 died of the consequences (Carasso, 1987, p. 2).

New:

V@ginal stimulation by doctors and midwives.

More details about the tasks of a midwife can be found in Catherine Blackledge, The Story of V, London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson. I have taken the following information from the Dutch translation, especially pages 273 + 291 + 345.

(Here I insert the 1 and the @ so that this page will not be blocked by Internet filters).

Stimulating and vibrating the v@gina was considered a normal task for medical doctors from the times of antiquity onwards. Doctors wrote quite openly about this practice, see for instance in the descriptions in books by Galenus / Galen who lived from 129-200 after Chr and in books by Äetius of Amida, who lived from 502-575). Well into the seventeenth century, medical men remained convinced that retaining semen in the human body for too long was bad for health, not only for men but also for women. Women were understood to produce and retain semen as well, especially when they were virgins or recently widowed - and thus they were prone to show signs of nervous disorders because of it. In order to relieve tension in these women, doctors or later on midwives would perform manual stimulation of the v@gina so that org@sm would result in a flow of v@ginal fluid, taking the female 'semen' along. Midwives would also use nicely perfumed oils on the inside of the v@gina and would insert pen1s like objects into the vagina. In order to combat 'hysteria' doctors also advised married nervous women to make love to their husbands more often. (Blackledge, page 273). However this medical practice of v@ginal stimulation was increasingly frowned upon at the end of the seventeenth century.

Seventeenth century doctors increasingly preferred to leave this manual task to midwives who gained quite a new field of expertise: "Let midwives anoint her fingers with [...] young mackarel mixed with musk, ambergris, civet and other sweet powders, and let them rub and tickle the top of the tube towards the womb, reaching the inner opening."

Another theory was the result of the belief that the uterus (womb) was moving freely about in the belly region and even upwards towards the throat region. All of this walking about could lead to suffocation of the womb, referred to as 'hysteria'. In order to remedy this, sweet scenting aromatic oils were inserted in the v@gina to lure the womb back down. Herbs (ginger, laurel) were also burnt and their fumes were released inside the v@gina after inserting a hollow metal fumigating instrument, shaped like a pen1s, with sieve holes. (Blackledge, illustration, page 290).

See the discussion of seventeenth century v@ginal syringes

(I use the 1 and the @ so that this page will not be blocked by politically correct Internet filters).

Other

tasks

Other

tasksAdditional tasks were to perform physical checkups for pregnant women and new born babies. If a child was born out of wedlock she was to ask for the name of the father and report it to the municipal authorities. Another task was to check the body of a still born baby or a baby who died after birth. Finally she had to assist in the schooling of midwives-in-training (Van der Borg, p. 40).

The midwife was not allowed to perform a baptism. If one feared for the baby's immediate death, midwives would sometimes perform a crisis baptism, but this practice was officially prohibited by the Reformed Synod of Gouda in 1589. All baptisms had to be performed within a church. Whether that actually happened is another question. (Van Peer, Archief, 1960, p. 300.)

Read about breast feeding and mothers milk.

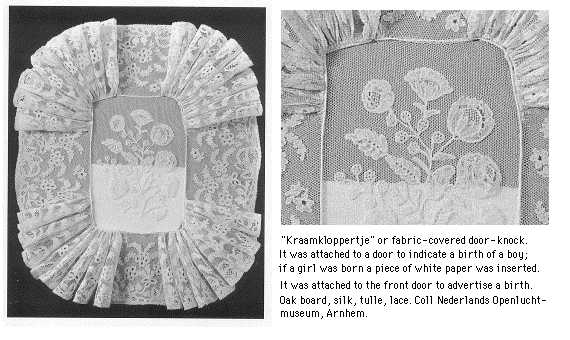

Birth announcement marker for the Front door of a house, a so called 'Kraamkloppertje'

Position

of midwives

Position

of midwivesMidwives were either holding a private practice in a town, or they were put on fixed wages by the municipal authorities. They were member of the guild of surgeons and thus the most extraordinarily advanced professional group among women.

In the seventeenth century Republic the midwife played a major role in assisting childbirth. Midwives worked under municipal ordnances and regulations (Dutch: 'keuren') which were published by the municipal authorities. Their training, diploma and appointments were well taken care of. Midwives were trained by the local surgeons guild, which had an appointed accoucheur. He was either a surgeon who had specialized in obstetrics or a medical doctor with special experience and craft. When complications arose, a midwive was obliged to call for professional advice from the accoucheur or medical doctor. But the birth process was still guided by the midwife. The municipal ordnances guaranteed a good training and quality ; they also offered protection from competition from out of town midwives (Houtzager p. 43).

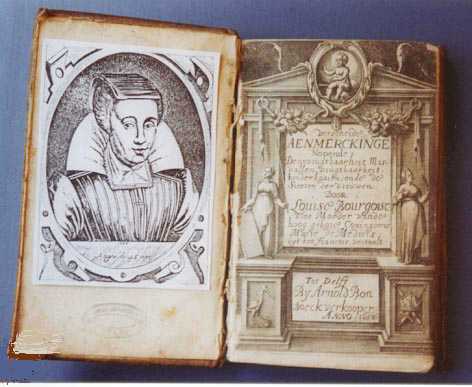

Above: Dutch edition of the book by Louise Bourgeoise, midwife to the Royalty of France. Published and printed in Delft by Arnold Bon in 1658. Nine years later, in 1667 Bon was also the publisher of a history of Delft - with included a poem written by Bon on the fame of both Fabritius and Vermeer. This copy of the Bourgeoise book is in the Delft Municipal Archive, photo copyright Kaldenbach.

According

to some historical sources, midwives were ill-paid for their core service, which

is assisting in childbirth. This necessitated taking on extra paid tasks such

as taking in pregnant women in their own homes for room and board; midwives

also were hired to take care of newborn infants (Van der

Borg p. 12). In 1784 Terne writes that midwives were not respected very

much by society during the 17the and 18th century. It was a job executed by

widows and lower class women (Van der Borg, p. 13).

In Leiden ten midwifes were active during the 17th century but just five during

the 19th century (Van der Borg, p.21). They were

the losers in competition with accoucheurs (male obstetricians) and surgeons.

Often ill tales were told about midwives and at the end of the 17th century

the position of accoucheurs was strengthened, and that of midwives weakened

(Van der Borg p. 41).

According

to some historical sources, midwives were ill-paid for their core service, which

is assisting in childbirth. This necessitated taking on extra paid tasks such

as taking in pregnant women in their own homes for room and board; midwives

also were hired to take care of newborn infants (Van der

Borg p. 12). In 1784 Terne writes that midwives were not respected very

much by society during the 17the and 18th century. It was a job executed by

widows and lower class women (Van der Borg, p. 13).

In Leiden ten midwifes were active during the 17th century but just five during

the 19th century (Van der Borg, p.21). They were

the losers in competition with accoucheurs (male obstetricians) and surgeons.

Often ill tales were told about midwives and at the end of the 17th century

the position of accoucheurs was strengthened, and that of midwives weakened

(Van der Borg p. 41).

In the countryside midwives were often self-taught. They received the necessary knowledge and experience in the craft of midwivery by hands-on training, obviously under guidance of other midwives. (Houtzager p, 41, 43; Schrader p. 52).

On behalf of the eastern Netherlandish town of Arnhem, vacancy advertisements were published in 1726 in newspapers published in Amsterdam, Leiden, Delft and The Hague (Van der Borg p. 24). The vacancy procedure included selecting proper applications by a selection committee, holding the job interview, checking testimonials, an examination after which the oath would be taken and the midwife was properly installed. In Arnhem a salary was paid which consisted of a flat rate and an amount for each birth (Van der Borg p. 24). If midwives were hired by another town after this thorough procedure, then her husband and children would often also move, all receiving citizenship in the new town. This indicates as appreciable social standing. Midwives's income was comparable to male artisans, which would be about 2 guilders per working day around 1660 (Van der Borg p. 129).

At all hours of daylight and night time the midwife's task brought her in the homes of a wide variety of social groups. In many cases the delivery will have taken place in dark, ill lit and aired rooms, often in unhygienic circiumstances. Nevertheless the rate of babies born alive per 1000 births was high.

Probably the oldest Dutch municipal ordnance in this field is that of Delft, dating from 1656; in other towns the ordinances followed later on - as in that of Amsterdam in 1668, and that of Utrecht in 1778 (Houtzager p. 45). Even before this year 1656 the Delft municipal practice was to apply exams for midwives.

This is the full text of the 1656 document.

|

Original text of the document, Delft 1656 |

Condensed translation by Kees Kaldenbach |

|

Dat de voorn. vroedvrouwen oock het gilde van de voors Cirurgijns soude mogen zijn subject ende jaarlijks nevens deselve haer gelt betalen. Soo ist dat de opgemelde Heerenvan de Weth considereerende de importantie van de voors sake en alvorens hier op gehad hebbende het advijs van stadts medicijns omme soveel als doenlijck alle ongelucken door de voorn naerlatigheijt veroorsaeckt werdende voor te comen goed gevonden hebben en geordonneert gelijk zij goed vinden en ordonneren mitsdezen dat so haestig selve een quaade geboorte comt te presenteren ofte dat de nageboorte aengroeijt en niet wel te krijgen is ofte de streng van dien bij ongeval van herden dewegangh ofte anders mochte comen te breken de vroedvrouwen gehouden sulle zijn een ervaren medicijn te doen roepen ten eijnde de selve haer raed geven can hoe sij sig in sulcken geval sullen hebben te dragen dat mede als de nageboorte niet heel maer aen stucken gaet de meergementioneerde vroedvrouwen haer niet bevordren sullen deselve weg te doen often in 't vuer te werpen voor en al eer sij aen een ervaren medecijn sullen hebben vertoont om te weten of deselve daer oock geheel sij oftte niet waerdoor anders menogmael veele doodelike accidenten en sieckten voortcomen dit alles op een boete van vijftich gulden en arbitrale corectie van schepenen dat verders deselve vroedvrouwen sig sullen hebben te wagten aen craemvrouwen eenige drancken poeijerkens of iet anders van consequentie in te geven ten warewat olije van zoete amandelen tusschen moeder en kint een lepeltje caneelwater camille bier ofte iet diergelijke van wijnigh importantie maer het selvige als buijten haer professie en boven haer kennisse sijnde de sorge van den medecijn bevolen laten op de boete van tien gulden telcken te verbeuren ende ten eijnde hetgeene vorss is te beter soude connen nagecomen en achter volght werden hebben de opgemelte Heeren goedgevonden gelijk zij goedvinden mits desen dat de voorn vroedvrouwen als mede andere bijmeesteressen van nu voortaen het chirurgijns gilde sullen sijn subject en jaarlijks nevens deselve mede haer gildegeld betalen sullen daer vorch de dickgemelte vroedvrouwen niet alleen genieten het recht van op de Anatomi kamer van de Chirurgijns haer examen te mogen doen maer sal oock den Doctor Anatomicus gehouden sijn sig als een vrouwelijk subject presenteert voo de selve particulierlijk in 't bijwesen van Stads Doctoren een demonstratie van de lijffmoeder en deszelfs appendentien te doen. Ende op dat het geene voorss. tot beter kennisse van de vroedvrouwen mochte comen sal ieder van deselve vroedtvrouwen dese in copie worden toegesonden omme haer daer naer te reguleren. Gedaen bij de Heeren van de Weth den 11 September 1656. |

Midwives must become member of the Surgeons Guild and pay the annual fee. Assisted by the city surgeon they will prevent accidents which could be caused by negligence. If and when a difficult birth arises, or when the placenta gets stuck of the umbilical cord should break, then midwives must call an experienced doctor for advice. If the placenta is not extracted entirely, then the midwives are forbidden to throw it into the fire, but they should show it to an experienced doctor, for this is the cause of many accidents and illnesses. All of this is punishable with a fine of 50 guilders and a lawful correction by the municipal eldermen. That the midwives must not give medicinal drinks or powders to women in childbirth except for almond oil, cinnamon water or other matters of minor importance. Other medication must be left to the doctors, on pain of 10 guilders punishment.

Midwives are entitled to education in the anatomy hall of the Surgeons Guild. When a female body is present the attending anatomist will teach them about the uterus and other connected organs. A copy of this letter will be given to all midwives so that they will comply to these regulations.

Published by the Delft Aldermen on 11 September 1656 |

In the Dutch version of this internet page a number of Dutch terms and definitions are explained. These have to do with tradition and folklore concerning childbirth.

Jan Baptist Bedaux & Rudi Ekkart, (ed.) Kinderen op hun mooist. Het kinderportret in de Nederlanden 1500-1700. Ludion Gent/Amsterdam. Exh. Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem 2000 en Koninklijk Museum van Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen 2001.

Helena Adelheid van der Borg. Vroedvrouwen: beeld en beroep. Ontwikkelingen in het vroedvrouwschap in Leiden, Arnhem, 's Hertogenbosch en Leeuwarden, 1650-1865. Wageningen Academic Press, Wageningen, 1992.

Catherine Blackledge, The Story of V, London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson. I have taken the following from the Dutch translation, pages 273 + 291.

Dedalo Carasso and Annemarie de Wildt. Een kind onder het hart ; zwangerschap en geboorte in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Exhibition catalogue, Amsterdams Historisch Museum, 1987.

Jacob Cats. Houwelick (...) 1625.

Barbara Duden, Geschichte des Ungeborenen : zur Erfahrungs- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte der Schwangerschaft, 17. - 20. Jahrhundert / hrsg. von Barbara Duden ... Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2002. - 328 S. : Ill., graph. Darst. (Veröffentlichungen des Max-Planck-Instituts für Geschichte ; 170) [ISBN 3-525-35365-0]

Donald Haks, Huwelijk en gezin in Holland in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Van Gorcum Historische Bibliotheek, nr 98, Assen, 1982.

Dr. H.L. Houtzager. Medicijns, Vroedwijfs en Chirurgijns; schets van de gezondheidszorg in Delft en beschrijving van het Theatrum Anatomicum. Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1979.

Dr H.L. Houtzager, Wat er in de kraam te pas komt. Opstellen over de geschiedenis va de verloskunde in Nederland. Erasmus Publishing, Rotterdam 1993.

Renée Kistemaker (ed.) Een kind onder het hart. Verloskunde, volksgeloof, gezin, seksualiteit en moraal vroeger en nu. Meulenhoff Informatief, Amsterdam & Amsterdams Historisch Museum, 1987.

Luuc Kooijmans, Vriendschap en de kunst van het overleven in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Amsterdam, Bert Bakker, 1997.

A.J.J.M. van Peer, 'De doop van Jan Vermeer' in Archief voor de geschiedenis van de katholieke kerk in Nederland, 2e jrg, afl III, nov. 1960, p. 299-307.

A.J. van Reeuwijk. Vroedkunde en vroedvrouwen in de Nederlanden in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Dissertatie, 1941 (collectie UB UvA)

G.D.J. Schotel Book title? . 1903, chapters 2-6, mentioned in Exh Cat De Gouden Eeuw viert feest, Frans Hals Museum 2011, p. 124 about Birth visit / De Kraamvisite.

C.G. Schrader's Memoryboeck van de Vrouwens. Het notitieboek van een Friese vroedvrouw 1693-1745. Bewerkt en ingeleid door Drs. M.J. van Lieburg. Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1984.

Marijke Spies, Des mensen Op-en Nedergang, literatuur en leven in de Nooordelijke Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw. Bulkboek Amsterdam/Barneveld, 2nd ed. 1985.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.