Maternity

dress and trousseau in the 17th century Republic

Maternity

dress and trousseau in the 17th century Republic Maternity

dress and trousseau in the 17th century Republic

Maternity

dress and trousseau in the 17th century Republic

In the course of their marriage, which lasted from 1653 to 1675, Johannes Vermeer and his wife Catherina Bolnes had no less than fifteen children. Eleven were alive in 1676 as was pointed out by Montias. In the Vermeer home the matters of pregnancy, midwives, childbirth, maternity dress and trousseau (baby room outfit) must have been quite central. No letters or diaries have come down to us which would shed light on life in their home. This text focuses on a few available historical sources.

Illustration top right: Watercolor by Abraham Delfos, ca. 1771, after a (now lost) painting by Gerard Dou. Coll. Westfries Museum, Hoorn.

Procreating is and was a duty and a necessity. Because of offspring, wealth remains within the falmily and one is sure about care by ones own children when getting old.

Nevertheless men and women, if they chose to do so, could do birth control by obtaining certain herbs from the apothecary. "If the apothecary would not provide certain herbs, a lot of children would be born." [ Dutch:"Waerder inde apteeck gheen heymelick cruytt, wat zouder menigh kinnercken comen uyt"] was a naughty rhyme once written by a Delft citizen. (Ach lieve tijd, Delft, 1995, p. 12).

There seem to be no depictions of pregnant women in the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century. Pregnancy was obviously considered as indecorous and not attractive and was thus kept out of public eye as much as possible. It may be doubted whether the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter by Vermeer (Rijksmuseum) is pregnant. She is wearing a blue satin bed dress (Dutch: "beddejak"). In French fashion pregnant women would sometimes wear a "robe battante", a wide garment which would cover up any sign of pregnancy. This also points towards evasion of publicly showing off pregnancy, which might be seen as indecorous. Pregnant women were encouraged loose fitting clothes, certainly not a tabbaard and a busk. (Marieke de Winkel, 1998, p. 331).

In

the seventeenth century the trousseau (baby stuff) consisted of the

following objects (see WNT

dictionary):

In

the seventeenth century the trousseau (baby stuff) consisted of the

following objects (see WNT

dictionary):

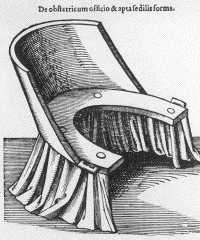

the materntiy chair (picture to the left),

the folding screen (against draft),

the maternity sitting basket,

bakermat,

the fire basket, vuurmant,

the tubs

and many other 'snorrepijpen' (= ?) had to be bought"

One could understand these extra objects "snorrepijpen" as

including:

the diaper basket

the potty chair

In Vermeer's inventory one only finds the bakermat and the fire basket, vuurmand. But then in 1675/1676 the Vermeers did not have babies around.

Purchasing

cost

Purchasing

costOn March 27, 1670 in the village of Graft in the Dutch province of North-Holland, nine months prior to his marriage date, one Cornelis Lourisz bought a trousseau on a auction of goods (Van Deursen, Graft, p. 65.). The clickable objects show examples of these objects from dolls houses. One should reckon that in the seventeenth century Republic a master craftsman could earn up to one or two guilders per working day:

A potty for f 0:6:8

A bakermat or large nursing basket

for f 0:8:0

A potty chair for f 1:6:0

A chair for f 0:3:0

A peat vat for f 0:10:0

A child's blanket for f 0:7:0

Total cost ca.f 3:0:0

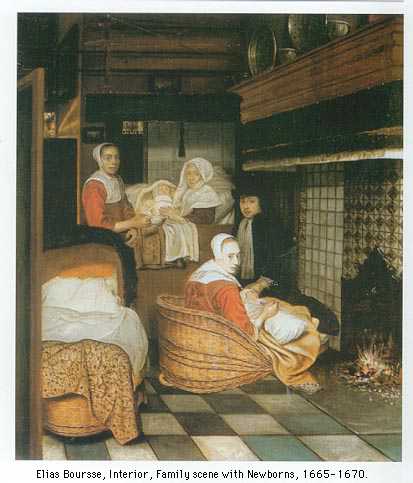

Midwives

MidwivesIn giving birth in the Dutch seventeenth century Republic the midwife and customs governing pregnancy and childbirth played an important role. Neighbors were essential in matters such as birth, sickness and death.

At the baptism there were special witnesses - often members of the family - who promised to be godfather and godmother. These would take charge of raising the child if both parents were to die. The witnesses traditionally offered a "pillegift", which is a delayed gift which was actually handed over after a number of months of a year when it turned out that the baby was still alive (Kooijmans, Vriendschap, p. 94).

Baptism

Before the Reformation the Roman Catholic church did have the sole and unique right to shape the ritual character of the great moments in human life: baptism, marriage, burial. After the reformation, from the 1570's onwards the Dutch Reformed Church did get posession of all church buildings in the Republic, but it provided a wide community service for the continuity of said great moments.

When taking care of baptism within the Dutch Reformed church, this act was seen - from 1578 onwards - as a general christian baptism, and not one of the Reformed faith in particular.

Marriage in a reformed church was open to all Reformed mebers, for a wide circle of sympathizers, but also for baptized outsiders such as Roman Catholics.

The Dutch Reformed church chose to perform burials without any ritual. Any dead person could be buried within the walls of a Reformed church. (Van Deursen, Kopergeld, p. 290-295).

Read about breast feeding and mothers milk.

Visit http://www.stolaf.edu/people/devries/docs/midwifery.html

Illustration all the way on top: Willem Laquy, copy after the tryptich 'Allegory of Art Training' by Gerard Dou, the central panel showing The Lying In Room, signifying the Nature or aptitude as part of training. Painting in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, detail of central panel which measures 83x70 cm. Houbraken chastized Dou for such a down to earch approach to allegory.

Literature

:

Literature

:

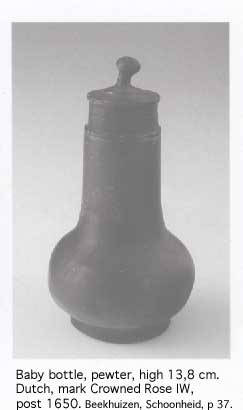

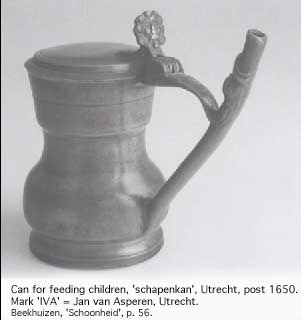

L.F.H.H. Beekhuizen, De schoonheid van het oude tin. Een overzicht van vijf eeuwen tin, Pilkington & Larousse, 's-Hertogenbosch 1998.

A.Th. van Deursen. Een dorp in de polder. Graft in de zeventiende eeuw. Bakker, Amsterdam, 1994.

A.Th. van Deursen, Mensen van klein vermogen; Het 'kopergeld' van de Gouden Eeuw, Ooievaar / Prometheus, Amsterdam, 1991.

Luuc Kooijmans, Vriendschap en de kunst van het overleven in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Amsterdam, Bert Bakker, 1997.

Ben Speet (ed.) 20 eeuwen Nederland en de Nederlanders. Deel 6: Geboorte, huwelijk en dood. Waanders Uitgeverij, Zwolle ism. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1998.

Marieke de Winkel, 'The Interpretation of Dress in Vermeer's Paintings' in Vermeer Studies, edited by Ivan Gaskell and Michiel Jonker, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 1998, p. 327-339.

Marieke de Winkel, ' "Eene der deftigste dragten": the Iconography of the Tabbaard and the Sense of Tradition in Dutch Seventeenth-Century Portraiture', Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 46, 1995, pp. 145-167.

Dictionary WNT: de Vrije, Verm. de Houw, 88, jaar 1687, cited in: De Vries en Te Winkel Het Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT) XXIII, column 1430; zie ook: Schouten, Oostindische voyag. I, 73., cited in WNT II,1, kol. 883)

*Did Catherina call herself Catherina Bolnes or Catherina Vermeer? Van Deursen has noted that women in the village of Graft held on to their own last names - or patronims such as Jansz. during the seventeenth century. (Van Deursen, p. 42).

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.