A bed or 'bedde' is found in a number of rooms, including the cooking kitchen, room D.

A bed mattress and eiderdown once owned by Vermeer's family member Neeltge Goris formed her single most costly household item - as we see from the stunning price of 60 guilders. (Montias, chapter 4).

In 1623 grandmother Neeltge Goris was also known as a "bedde vercoopster", bedding saleswomen.

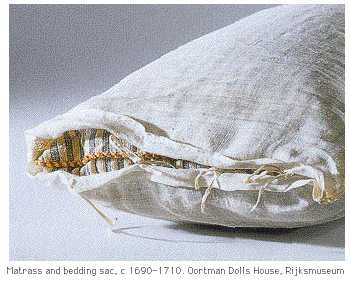

Another source confirms the high price of a bed - and explains that one has to imagine three layers: A rather flat bottom mattress cover filled with either bedstraw, horse hair or sea grass. On top of that was a soft cover filled with feathers, down or 'kapok from silk-cotton trees'. A person would sleep on top of these two layers and would be covered with sheets and blankets. (Wijsenbeek, p. 182-183)

Every day the sheets and blankets were removed from the matresses and folded in such a way that the head end and the smellier foot end could not be mixed up. The pillows had to be shaken and aired for an hour, in order to dry the feathers, which otherwise tended to lump "om de vederen te doen droogen, die anders klonteren." Then the beds had to be made up again. (Pijzel, Pronkpoppenhuis, 2000, p. 168).

Textile expert Marieke de Winkel wrote in 2001: Sometimes the term 'bedde' is used to indicate the matress only, but it indicates the entire bed at other times. See also pillow.

See also pregnancy and sexuality.

Note:

Photo Copyright Rijksmuseum Foundation. The Rijksmuseum has

graciously assisted in this project Digital Home of Johannes

Vermeer. The author was given permission to make a selection in

the vast photo archive and this material has been made available by

the Rijksmuseum.

Note:

Photo Copyright Rijksmuseum Foundation. The Rijksmuseum has

graciously assisted in this project Digital Home of Johannes

Vermeer. The author was given permission to make a selection in

the vast photo archive and this material has been made available by

the Rijksmuseum.

This object was part of the Vermeer-inventory as listed by the clerk working for Delft notary public J. van Veen. He made this list on February 29, 1676, in the Thins/Vermeer home located on Oude Langendijk on the corner of Molenpoort. The painter Johannes Vermeer had died there at the end of December 1675. His widow Catherina and their eleven children still lived there with her mother Maria Thins.

The transcription of the 1676 inventory, now in the Delft archives, is based upon its first full publication by A.J.J.M. van Peer, "Drie collecties...", Oud Holland, 1957, pp. 98-103. My additions and explanations are added in square brackets [__]. Dutch terms have been checked against the world's largest language dictionary, the Dictionary of the Dutch Language (Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal , or WNT), which was begun by De Vries en Te Winkel in 1882. In 2001 many textile terms were kindly explained by art historian Marieke de Winkel.

Illustration taken from the recently published handbook on Dutch Doll Houses by Jet Pijzel-Dommisse, Het Hollandse pronkpoppenhuis, Interieur en huishouden in de 17de en 18de eeuw, Waanders, Zwolle; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2000, ill. 164 and 165.

Montias, J.M., Vermeer and his Milieu, A Web of Social History, Princeton 1989.

Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, Th., Achter de gevels van Delft. Bezit en bestaan van rijk en arm in een periode van achteruitgang (1700-1800) [Hilversum 1987].

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 2, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.