![]() by

Kees Kaldenbach, Private Art Tours

by

Kees Kaldenbach, Private Art Tours

Viewing tip: this article should be viewed in a frame with 3 sections. If you do NOT see this division, please restart from www.johannesvermeer.info.

Go Fly like a bird over Delft, 1660

(Dutch language version? click Nederlands.)

Large image of this View of Delft.

We

see a glorious partly cloudy sky during early morning. It has just

cleared up after a sudden bout of rainfall. Under this expanse of

clouds and blue sky the crisp outline of the town of Delft is

visible. We are looking at the painting 'View of Delft', an

astonishing and moving achievement by the Dutch painter Johannes

Vermeer.

We

see a glorious partly cloudy sky during early morning. It has just

cleared up after a sudden bout of rainfall. Under this expanse of

clouds and blue sky the crisp outline of the town of Delft is

visible. We are looking at the painting 'View of Delft', an

astonishing and moving achievement by the Dutch painter Johannes

Vermeer.

In this famous painting we see a shaft of sunlight which strikes the roofs of the houses along the Lange Geer canal and the tower of the New Church (nrs 9 and 10 - see numbers on the line drawing).

There is an attractive contrast between these highlighted parts of the houses and the tower and their shadowy surroundings, creating a sense of depth. Seeing this painting's vibrant luminosity has remained a fascinating experience for many generations of viewers from the 17th Century to the present. Vermeer's 'View of Delft' was the highlight of the 1995-1996 Vermeer exhibition which was first shown in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC and later on in the Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, The Hague.

At this moment the Mauritshuis home page shows a small reproduction of this painting. On another homepage the full View of Delft is shown. The set of Vermeer paintings in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum may be seen there in great detail. Yet another home page shows all known Vermeer paintings. For easier viewing please find a high quality colour reproduction in an art book while reading this home page. My 1982 article in Artibus et Historiae (co-authored with Arthur Wheelock, jr.) is now online.

In recent art history literature it has been assumed that King William I of Orange (who reigned 1813-1840) appreciated the painting and decided to buy it because "knew that one day he too, would be interred in the crypt under his ancestor's monument". The story of the purchase of the View of Delft is more complicated than that. The King did not actually choose the painting himself, it was chosen by the director of the (precursor to the) Rijksmuseum and his advisor. With regard to purchase policy of paintings in general the histories of the Royal Collection of paintings Mauritshuis and the Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam are quite intertwined during the reign of William I. In 1822 there was a batch of paintings to be distributed between the Rijksmusem and the Mauritshuis and the director of the Rijksmuseum actually preferred another painting at that time. It happens to be The Hut by Adriaen van der Velde, a painting which now would be not quite considered earth shattering.

Be that as it may - William I would have indeed appreciated the Vermeer painting as it highlights the tower of the New Church (10) which is given a prime role on the middle right side of the painting. This tower is part of the New Church which houses the marble grave monument of his predecessor Willem of Orange (who reigned in the 16th C.).

Many generations of art lovers, laymen and art historians alike, assumed that Vermeer painted an exact rendering of Delft as it had been during his lifetime - around the year 1660. Let us - in order to find out whether this is the case - take a guided tour through this painting.

Towards the right Vermeer depicts the Rotterdam Gate (11), which consists of the main building and the barbican with the twin towers (12). Just in front of it, a double draw-bridge leads to the series of small shipyards alongside the Schie canal, of which the first is visible on the far right hand side.

In the middle of the painting Vermeer depicts the Schiedam gate (8) of which only the main building (not the barbican) existed during Vermeers' days. This main building is built of red brick, alternating with thin layers of limestone (brick being locally produced and affordable, limestone having to be imported at great cost). Its gate opening was sealed off for traffic.

Immediately to the left is a wooden shed built in 1611, storing large wooden material for warfare use: palissades, planks, beams, movable water and grain mills on carts, battering rams, and baskets for moving earth. This is one of the series of armament buildings which define Delft as a military town. In those other buildings harnesses and helmets were kept, and even uniform belts made out of elk leather, a commodity obtained by trade in distant lands. A document written 21 oktober 1661 shows that each year two new cannon were cast, bearing the crest of Delft. Each of these cannons could fire a 24 pound cannon ball.

Behind this main gate building, towards the left, we see the roof of the Armamentarium, the weapons' warehouse (6), which still stands today.

Directly to the left of the Schiedam gate (8) is the Kethel gate, which gave wagons and coaches direct access from the town itself to the quay along the Schie (7), passing the many moored ships.

The Dutch artist Jan de Bisschop depicted the view from a vantage point somewhat further towards the left. That which remains fuzzy and not defined in Vermeer's painting is clearly delineated on his washed pen drawing: The Kethel gate (B1), Schiedam gate (B2) and, across the water, the barbican of the Rotterdam gate (B3). Quite a few people stand about, waiting on the quay and the dam which extends in front of the Schiedam Gate. The wall towards the left, which was backed by a dam of earth, is fortified with semicircular towers. This site presents a Virtual Reality movie with a walk through these gates.

The Schiedam and Rotterdam gates were built after 1394, but were still unfinished in 1514. In 1590-91 they were both modernized according to the architectural tastes of that time. The architects' drawing of the city side facade of the Rotterdam Gate has been preserved.

The barbican of the Schiedam gate had crumbled by the 16th. C. and was duely demolished, but the dam on which it stood was preserved. The triangular earthworks of the rest of the fortification were dug away from 1614 onwards, creating the triangualar 'Kolk' harbour at the point where the Schie canal meets the town of Delft. Up to the middle of the 18th C. at all town gates 'gate money' (a city excise tax) was levied on all goods passing on road and water ways.

In 1695 another Dutch artist, Josua de Grave made the drawings of the view from the city towards Rotterdam gate (G1) Schiedam gate (G3),and Kethel gate (G4). These are so rich in detail that we are practically able to walk about in this scene. Again they help us understand what Vermeer has painted.

At the left, towards the end of the barbican of the Rotterdam gate, projecting out from the walls at the far end we see the twin octagonal towers (G2) flanking the draw bridge. High up, in between those towers was the guard room with strategically positioned holes in the floor. The narrow road leading from the drawbridge towards the main building is slightly bent, keeping enemy projectiles shot from or through the drawbridge from reaching the city streets. This narrow road is flanked by defence hallways built on arches. One may observe their architecture in the East Gate, whicj has been preserved. The main gate passage within the main building could be closed of by lowering a massively heavy grill. In the upstairs room from which this contraption was worked there were a number of holes in the floor through which foes could again be attacked. This barbican was demolished after 1695 - probably due to its poor state of repair. However, the main gate stood until the demolition hammers struck in 1836.

Vermeer

has depicted people and a tow barge on the foreground in order to

enliven the scene. Amongst these persons who are standing about on

the quay are three wealthy burghers, wearing distinguished attire

(13). They stand close to the tow barge, of which we see the back end

with the rudder. The strange thing is that Vermeer showed this barge

in a non-functional position as the opening for embarking and

disembarking, of this barge moored like this, is at the side of the

water, not the quay side. The barge has a red and white wooden

structure covered with tent-like material on it to protect its

passengers against wind and rain.

Vermeer

has depicted people and a tow barge on the foreground in order to

enliven the scene. Amongst these persons who are standing about on

the quay are three wealthy burghers, wearing distinguished attire

(13). They stand close to the tow barge, of which we see the back end

with the rudder. The strange thing is that Vermeer showed this barge

in a non-functional position as the opening for embarking and

disembarking, of this barge moored like this, is at the side of the

water, not the quay side. The barge has a red and white wooden

structure covered with tent-like material on it to protect its

passengers against wind and rain.

Towards the left hand foreground stand two women in peasant dress, one of them carrying a basket on her arm, and holding a square cloth draped over her forearms (14). A third woman who is dressed like a farmer stands towards the left of the burghers. On an x-ray photograph of the right hand part of this bank another man is visible, who was later painted out by Vermeer for reasons of composition.

Moored at the shipyard towards the far right are two herring busses (plural of herring buss), ships which were specifically designed and crafted for the profitable herring fishery (17). The main mast of the herring ships has been lowered and hoisted away for repair. Midships the opening is visible through which the herring nets were pulled in. More information on the subject of ships: click The ships on View of Delft; the most exact dating of this painting ever published.

The striking 'photographic effects' in Vermeer paintings have been discussed many times. During his preparations he probably did use a Camera Obscura (a wooden box with a lens, a mirror and a frosted glass pane, comparable to an early photographic camera) as a source of research or inspiration. If the sun would hit and sparkle off the wet surface of this ship, a view through a Camera Obscura would present sets of fuzzy rings - called circles of confusion - on the frosted glass. Oddly enough Vermeer has copied this optical effect in a shaded area on the side of the ship, outside direct sunlight, thus not in a logical spot.

Far away, in front of the city wall (15) a number of people are visible as tiny figures on the quay, where a number of medium size sailing ships are moored. In the water, against the side of the Rotterdam gate one sees a number of tow barges (16) of the same kind as the one visible in front towards the left. They have masts decorated with a spiraling red stripe. These barges were pulled by tow horses who were attached to the barge by a very long rope. The line went from the horse up to the top of the mast at the front of the barge and from there the line went to the back of the ship where it was knotted near the skipper who stood at the rudder.

There was also another type of inland transport ship which had a sturdy mast. In a fair wind a sail was hoisted from this mast. If the wind was insufficient, a horse would pull the tow rope and move this barge.

But these tow horses (often old beasts who had most of their productive life behind them) were mostly employed to tow the specially crafted slender tow barges of the type shown by Vermeer. The captain's assistant followed the tow path along the canal which was often especiallly designed for this purpose. In the 17th Century Dutch towns were connected by a network of line services by tow barges, then one of the most advanced public transport systems in the world. They provided scheduled day time (actually day light) transportation which was frequent, dependable, comfortable and affordable, linking many towns in Holland. For the night rides the heavier sailing barges were employed.

For more information on shipping click The ships on View of Delft; the most exact dating of this painting ever published

One particular row of houses which Vermeer painted is still standing in Kethel Street (see letter K on the detail of the Figurative Map). The Kethel street runs perpendicular to the quay. In Vermeer's painting one notices some of the gable tops sticking out just above the city wall. The position of these gables is difficult to read as some are next to each other and others are part of buildings further away. Of the pointed gable to the left we only see the upper triangle (1). This belongs to the building somewhat further away which has a large horizontal roof (3). Under this triangle we see a row of three small stepped gables (2). These stand in front of the large building just indicated and are part of the houses along the Kethel street (K).

Careful measurements carried out in the early 1980's show that the rhythm interval of these houses (in this Vermeer painting each is about 40 mm wide) exactly mirrors that of the plots of the present day homes (which are each about 4 m. wide). After these measurements were carried out, all of these buildings were sadly demolished. One of those houses had a stone ornament which bore the inscription 1670. In depicting this row of houses Vermeer clearly did copy reality very faithfully.

He

did however choose not to do so in depicting the reflection of the

buildings in the water of the Schie. This reflection has been

extended by Vermeer in order to visually tie the foreground to the

background. The long horizontal roof mentioned before (3) cannot be

pinpointed definately when studying 17th and 18th century maps and

profile views of this part of Delft. It is possible there was a large

roof belonging to the brewery 'De Papegaey' (the Parrot) with the

slender tower (5). Probably Vermeer has adapted the height and width

of this roof in order to meet his compositional needs, stressing

horizontality. The position of the barbican (front gate) of the

Rotterdam gate has also been shifted towards the side in order to

achieve a horizontal frieze-like effect. For this very reason the

bridge between these gates has been rendered rather flattened and

stretched.

He

did however choose not to do so in depicting the reflection of the

buildings in the water of the Schie. This reflection has been

extended by Vermeer in order to visually tie the foreground to the

background. The long horizontal roof mentioned before (3) cannot be

pinpointed definately when studying 17th and 18th century maps and

profile views of this part of Delft. It is possible there was a large

roof belonging to the brewery 'De Papegaey' (the Parrot) with the

slender tower (5). Probably Vermeer has adapted the height and width

of this roof in order to meet his compositional needs, stressing

horizontality. The position of the barbican (front gate) of the

Rotterdam gate has also been shifted towards the side in order to

achieve a horizontal frieze-like effect. For this very reason the

bridge between these gates has been rendered rather flattened and

stretched.

When travelling towards Delft, the tower of the Old church appears as massive and imposing as that of the New Church. In Vermeer's painting the tower of the Old church is hardly noticeable (4), whereas that of the New Church has been rendered prominent and twice too wide.

Moreover, the bell tower proves to be empty! Recently, documents were discovered which prove that the carillon bells of this New Church tower were renewed and were hoisted down in the summer of 1660 during a restauration by the Hemony firm. Vermeer worked slowly and carefully on his paintings, which he put to the side to dry from time to time. We know this as paint layers aplied later has seeped into the cracks of earlier layers of paint. The empty bell tower thus points at a date of 1660, nicely confirming the date which was proposed on stylistic grounds. The painting may have been finished in the period 1662 to 1665.

Wandering tourists sometimes err in thinking the present day East Gate of Delft - with its photogenic twin towers - to be the very gate which Vermeer depicted. The real stand point (S) which Vermeer chose was however to the south of the Armamentarium, across the expanse of water of the Schie at the second or third floor of a home on the Hooikade (Hay quay). But alas! In 1982 the view from this vantage point (at number 29) was disappointing and since its demolition this vantage point does not exist anymore. The Delft planners have however built a square which is called 'Plein Delftzicht' (Delftview square), with a semicircular terrace which allows one to contemplate Delft as it was.

Today, no single stone reminds us of the two ancient gates since the demolition of the Schiedam gate in 1834 and the Rotterdam Gate in 1836. Heavy traffic now whizzes through the ghosts of both gates. Only the Armamentarium, the buildings along the canals and two facades along the Kethel street remind us of Delft as it was in the days of Vermeer. But its facade has lots the stepped gable and looks quite different.

Final notes 1 (2003).

The painting itself was purchased by the Dutch state (and placed in the King's gallery) in 1822 for the then considerable amount of 2900 Dutch guilders - equalling about six annual salaries of a skilled craftsman. The 1822 sale catalogue in which the painting was sold indicated that the majority of the paintings in this sale originated from the Stinstra collection in the northern Frisian town of Harlingen. However, the well crafted 1996 exhibition catalogue of the great Vermeer show provides us new insights about its provenance. The painting was actually never in Harlingen but was part of the Haarlem collections of W. Kops and lord Teding van Berkhout (for these findings see also the -bilingual- magazine Mauritshuis in focus, Dec. 1995).

Drawings and engravings of Dutch towns were indeed a very popular commodity on the 17th and 18th.C. Dutch market - thus a number of specialized artists such as Abraham Rademaker turned out views of cities in great numbers. For our subject it is a boon that the section of Delft Vermeer depicted was not only striking but also a busy ferry port. Therefore artists waiting for their barges to depart sometimes made sketches of this area - thus enlightening us two or three centuries later.

More details on the opening of the official herring fishing season are given in the book: Eelco Beukers, Hollanders en het water, Twintig eeuwen strijd en profijt 2, Hilversum, Verloren, 2007, p. 350. Initially when the herring buis was invented the season opened on St Michaels day, September 29. Then it was brought forward to St Bartholomews Day, August 24 And then for many centuries it was fixed on St Johns Day, June 24. The 19th + 20th century date was about June 4 to June 15, depending on the harbour. If we accept the June 24 date as a new fact, then the time frame of the painting should be set more loosely some weeks later.

Some small errors were fixed.

One may look for exact position of houses and their inhabitants at this Geographical Information System (GIS) for Delft:

http://historischgis.delft.nl/historischgisdelft/

and then find more detailed info about the persons found at

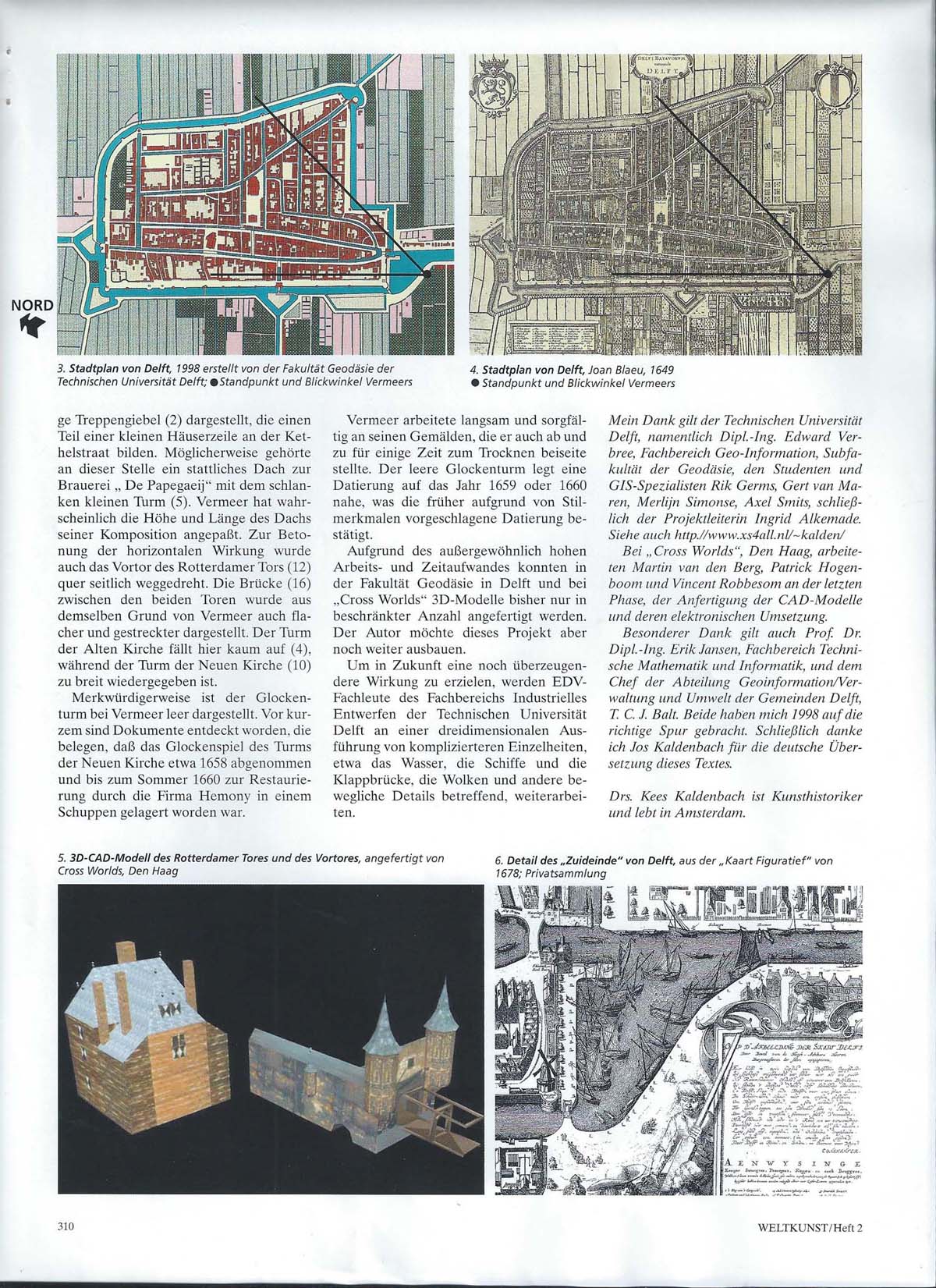

Article about a 3D project, executed by the Delft University of technology. Article in German,

Ein Flug uber die 'Ansicht von Delft' : Jan Vermeers Meisterwerk von 1660 als virtuelle Welt ,

Published in Weltkunst, 1999, p. 308-310.

For more publications click author.

Kees Kaldenbach also gives Private Art Tours

Abstract artist Peter Struycken on Johannes Vermeer.

For further discussion of ships and barges click The ships on View of Delft; the most exact dating of this painting ever published

A review of the book Vermeer Studies on the Vermeer colloquium of 1995-1996: Gaskell. The same book is discussed by me in Dutch; Kaldenbach

Jonathan Janson paints in Vermeer's style and explains how he does it:

http://www.essentialvermeer.20m.com/

http://howtopaintavermeer.fws1.com/

Comments?

Email me at kalden@xs4all.nl

Comments?

Email me at kalden@xs4all.nl

I will sign off with a respectful salute to Vermeer for leaving to us his breathtaking heritage, in particular his two largest paintings 'The Art of Painting' now in Vienna, which gave me such a jolt when I first saw it in 1975 and the 'View of Delft' which is discussed here. Although much is now known about both paintings they remain magical and wonderfully enigmatic. Thanks to the library staffs of:

Thanks also to Nico Bos, Marten Hoekstra for their help in designing this home page.

Click here for related Vermeer projects.

These images and this text are copyrighted, 2003.

Launched summer 1997. Last update October 25, 2011.