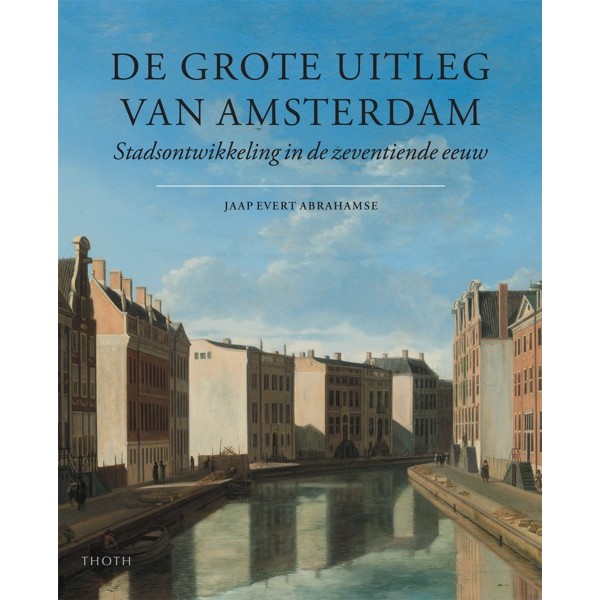

Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw (Toth; Bussum 2010) 432 p., ill., €39,90 ISBN 9789068684919

Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw (Toth; Bussum 2010) 432 p., ill., €39,90 ISBN 9789068684919by Kees Kaldenbach

See the edited original Dutch review published in

Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw (Toth; Bussum 2010) 432 p., ill., €39,90 ISBN 9789068684919

Jaap Evert Abrahamse, De grote uitleg van Amsterdam. Stadsontwikkeling in de zeventiende eeuw (Toth; Bussum 2010) 432 p., ill., €39,90 ISBN 9789068684919

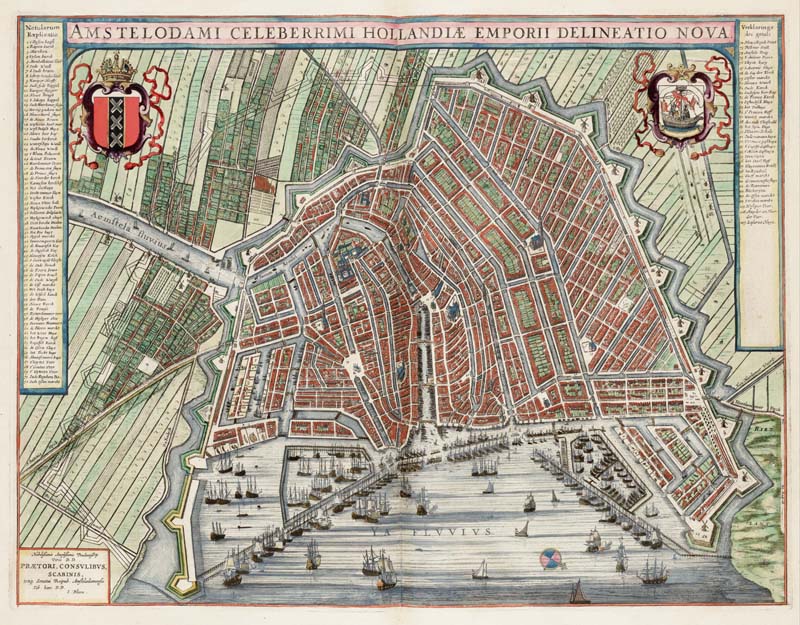

De Grote Uitleg van Amsterdam (The Great Amsterdam City Expansion. City Development in the 17th Century) a book by Jaap Evert Abrahamse, describes the administrative process of designing, financing and engineering the great semicircular canal system of the city of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. The book was presented during a meeting held in the City Archives (Stadsarchief) on 20 January 2010 just after the author had received his doctorate from the University of Amsterdam. The Stadsarchief building was a suitable setting, as it had served as the place in which the book was developed during a gestation period of some ten years.

The second founding institution at the heart of this book was the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age, a multi-disciplinary group of specialists from the Netherlands and abroad, who meet several times a year within the University of Amsterdam for a presentation, followed by discussion. Both the Archive and the Centre have been central to the author’s research, providing a basis for his archival research and the interpretation of available data.

Amsterdam knew four series of city expansions, the 1e-4e Uitleggen. In his book, Abrahamse demonstrates that the third large expansion of the city of Amsterdam that began around 1612 was to become a classic example of thoughtless planning; inept management resulting in a “governmental infarct” during the execution phase. In contrast, fifty years later the fourth city extension from ca. 1660 became a resounding success for the city government. The new design, planning and execution methods were well- prepared. Day-to-day affairs were strictly controlled, resulting in a financial break-even situation. A remarkable finding is that the digging of the canals was necessary in the first place to provide sufficient ground to raise the platforms on which the building blocks were planned and provide a transportation route for the building materials. During the seventeenth century, finding the earth with which to raise up plots of real-estate land was a continuous pressing problem. Steeling earth was a common offence of which citizens were guilty, one harming the interests of the other.

The final section of the book, as a sort of an annex to the planning story, deals with the disastrous environmental pollution of the canals, lasting from the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. The result was horrendous stench emanating from the waters of the canals in the centre of Amsterdam. They were continuously polluted by household refuse, sewage, cadavers and industrial waste. The incapacity of generations of well-meaning government officials and engineers to do anything about it lasted for nearly three centuries.

The final section of the book, as a sort of an annex to the planning story, deals with the disastrous environmental pollution of the canals, lasting from the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. The result was horrendous stench emanating from the waters of the canals in the centre of Amsterdam. They were continuously polluted by household refuse, sewage, cadavers and industrial waste. The incapacity of generations of well-meaning government officials and engineers to do anything about it lasted for nearly three centuries.

Good books about the Amsterdam city extension have been written before. In 1991 Paul Spies and Annemieke van Oord-de Pee produced their handsome Grachtenboek. The enormous Herengrachtboek described the process of construction and a list of inhabitants for each address, throughout the ages. The book series Amstelodamum and the Dutch journal Ons Amsterdam (Our Amsterdam) have published fragments of design stories. Hundreds of other books and magazine articles have told the story as well from various points of view.

At the heart of Abrahamse’s research was the determination to start with a blank slate in the City Archives. Radically, he then took available charts and maps and subsequently read and interpreted the many thousands of hand-written vroedschapsresoluties, or city government resolutions. These source texts of government decisions are extremely brief in style, and do not usually state the considerations and reasons by which the city government arrived at a certain decision. Abrahamse then entered this vast collection of raw source material in a database during the project’s initial phase, and subsequently analysed, classified and made the vast body of data comprehensible.

During the ceremony in which the author was awarded his doctorate, the professors questioned problems arising from this methodology. They asked whether handling this limited source – only maps and vroedschapsresoluties – provided a sufficient basis for writing a general history, or instead, whether a broader vision on a greater scope of sources such as books, laudatory poems, and other archival documents would have been preferable. A moment of hilarity; one professor mentioned that this thesis was too thorough and not broad enough, while a colleague said that on the contrary the product was too wide and not sufficiently detailed. At the end of the proceedings, after 15 minutes of deliberation behind closed doors, Abrahamse received a his degree Summa Cum Laude, something only bestowed on some 5% of Dutch doctoral theses. This stamp of quality also characterizes the two institutions at the heart of the author’s research, the Stadsarchief and the Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw.

During the ceremony in which the author was awarded his doctorate, the professors questioned problems arising from this methodology. They asked whether handling this limited source – only maps and vroedschapsresoluties – provided a sufficient basis for writing a general history, or instead, whether a broader vision on a greater scope of sources such as books, laudatory poems, and other archival documents would have been preferable. A moment of hilarity; one professor mentioned that this thesis was too thorough and not broad enough, while a colleague said that on the contrary the product was too wide and not sufficiently detailed. At the end of the proceedings, after 15 minutes of deliberation behind closed doors, Abrahamse received a his degree Summa Cum Laude, something only bestowed on some 5% of Dutch doctoral theses. This stamp of quality also characterizes the two institutions at the heart of the author’s research, the Stadsarchief and the Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw.

Ambahamse’s De Grote Uitleg van Amsterdam is a splendid, voluminous and richly illustrated book. As it is based on some ten years of archival study and analysis it presents a new framework of understanding and insights, while also providing a number of formerly little-known facts about both the third city expansion from ca. 1612 and the fourth extension from ca. 1660. (For instance, did you know that there were no street signs in Amsterdam ? Or that there was a city official appointed as a ‘urine carrier’ (‘pisdrager’), who contrary to city resolutions, dumped the contents of full chamber pots in the waters of the canals behind City Hall , now the Royal Palace on the Dam Square?

The Dutch text is crystal clear, the language illustrative, the sentences refreshingly short, clear, business-like and expressive. In the entire book I came across just one oddly phrased sentence, on the bottom of page 262. The number of spelling errors and typos is miraculously zero. Humour has been restricted to a single witticism (“bio-industrie”) on page 272. In reading Abrahamse’s main text I was struck by the high number of new information, opinions, analyses and insights that turned out to be just a bit different from what I had gathered initially from the literature, resulting from the collective wisdom held to this point by hundreds of former authors.

There is one serious criticism. On p. 330 Abrahamse writes that the city government had been guilty of not solving the far too low land-surface level of the Jordaan working class district. This resulted in water management problems, humidity and stench. However, several chapters earlier, the author states that the Jordaan had been embraced under the wings of Amsterdam who rebuilt its outer fortification walls in an outwards position. The Jordaan was a district known as a largely illegally-inhabited and disorderly area of squatters in use for both residence and industry. At the beginning of the third city extension project of 1612, the district contained no less than 3300 buildings made of wood and/or bricks. During the decades that followed, those buildings were clad with brick and given tiled roofs to lessen the danger of fire, as a result of pressure from the Amsterdam city government. Often built without due paperwork, houses were often just positioned alongside many ditches, yielding a pattern which can still be seen in the canals in the Jordaan that connect so oddly with the Prinsengracht canal. The series of side streets positioned at straight angles – such as the street yielding a sightline to the clock tower of the Westerkerk (Wester Church) are however, the results of planning and urban design considerations. In order to construct those side streets some demolition and financial recompense was necessary. Raising the ground level in the Jordaan could have only taken place when and if the entire set of existing buildings were demolished. This would have been a prohibitive step not only in terms of cost, but also due to the threat of wholesale insurrection by the poorer inhabitants of the area.

For 17th century Amsterdam city government officials it was a delicate balancing act, requiring friendly response sand judicious actions to realize the enormous scale of urban expansion at nearly no final costs, in order to build a useful, beautiful and profitable city.

Kees Kaldenbach

Kunsthistoricus te Amsterdam

Drs. C.J Kaldenbach, Art historian, Amsterdam.

====================

====================Adriaen Coorte, by Quentin Buvelot, book & exhibition catalogue.

De Grote Rembrandt, door Gary Schwartz, boek.

Geschiedenis van Alkmaar, boek.

Carel Fabritius, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

Frans van Mieris, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Grove Art catalogue, book.

Vermeer Studies, Congresbundel.

C. Willemijn Fock: Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld, boek.

Het Huwelijksgeschenk (1934), boek over de egoïstische vrouw, die haar luiheid botviert.

Zandvliet, 250 De Rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw , boek + nieuwe stippenplattegrond!

Ik doe wat ik doe, teksten van Lennaert Nijgh , boek + cd

Het Rotterdam Boek, boek.

Bouwen in Nederland 600 - 2000, boek.

Hollandse Stadsgezichten/ Dutch Cityscape, exhib. cat.

TEFAF 2008 art fair

More info about the author click author.

This page launched 2011, updated july 2916.

Research and copyright by Kaldenbach. A full presentation is on view at www.xs4all.nl/~kalden/