Read about law and order!

In 1675 Johannes Vermeer and his wife Catherina Bolnes had eleven living children. A good number of them must have been of the school-going age. But we can only wonder what kind of school they went to. Five types of schools are to be considered.

1) Extended kindergarten or 'ABC-school'

2) Dutch language, official school, connected to the local Dutch reformed church

3) Dutch language private school

4) Dutch language private school with an additional French and Math class (and afterwards perhaps:)

5) The Grand or Latin school.

The ideal of the Dutch reformed religion was that everyone could privately read and study the bible [both the Old and New Testament]; therefore mastering the art of reading was encouraged by the Dutch Reformed Church. More common people could read in the Republic than elsewhere in Europe. An interesting question is whether one read aloud or in silence. There are reports that one commonly read aloud.

1) Extended kindergarten or 'ABC-school' was for children between 3 and 7 years old. Within this school the younger groups were often taught by women, being either an independent teacher or the spouse of a male schoolmaster. The rudiments of the alphabet were taught by repeating and rereading texts in various fonts in upper and lower case: gothic, straight roman, italic roman and handwriting. Printed study and reading material was very scarce in schools. At home people might have owned a bible printed in Dutch, but owning a full book case like Vermeer did would have been exceptional in the lower classes.

2) Dutch language official school was for children between 5 and 12 years old. School teachers were partly paid for by the board of the local Dutch reformed school (annually they paid an amount between some 20 guilders to about 100 guilders) and partly by school fees paid by parents (a number of stuivers / 5 cent pieces), depending on the requirements for teaching which could be limited to reading only - or could be both reading and writing or could encompass both reading, writing and arithmetic. As this total amont of income was often insufficient to live from, an extra source of income was needed. In that case the schoolmaster cold take on another function related to the Dutch reformed church - such as sexton or grave digger. There was no teacher training college. In some smaller towns and villages the schoolmaster was barely able to write, and education was not very enticing. Upon the age of 10 years most boys were transferred to a master in order to learn a trade (beer brewing, weaving etc.) (Van Deursen, Klein vermogen, p. 140).

3) Dutch language private school was for children between 5 and 12 years old. It was fully funded by tuition money which was higher than that in regular schools.

4) Dutch language private school with an additional French and Math class was for children between 5 and 12 years old - with French from age 9.

These last two types of private schools were commercially run by private individuals without getting financial support from either the church or the city government. In order to survive the male or female school master (or a team consisting of the school master and his wife) were thus forced to ask for tuition fees. Cheap schools had many pupils, and expensive schools had few students.

The

city government did have a list of requrements for founding new

schools, but did not execute any quality control. One should not

think too highly of the educational level of the Dutch language

private school curriculum. However, compared to other countries in

Western Europe a high percentage of the population in the Dutch

Republic was literate.

The

city government did have a list of requrements for founding new

schools, but did not execute any quality control. One should not

think too highly of the educational level of the Dutch language

private school curriculum. However, compared to other countries in

Western Europe a high percentage of the population in the Dutch

Republic was literate.

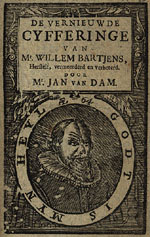

Apart from reading and writing the content of religious teaching was considered important. Strangely enough arithmatic was not on each school programme, but it formed part of the curriculum of the French schools. For mathemathics the now famous Bartjens book was a standard math method.

For morning classes the Dutch language private school opened at 8:30 hrs with a communal prayer. The several year groups were mixed together in one room; logically the elder pupils instructed the younger. There was no frontal classroom teaching to the entire group, but teaching took place in small groups at the teacher's table.

The male or female school master tried to call each student to the table at least twice a day for instruction and there was a inspection on the written school work - and to check proper development of knowledge.

On a daily basis the older pupils helped the younger ones and both parties thus gained important knowledge (by teaching and learning) which may be compared to present day Dalton type of education. The lunch break lasted from 11:30 to 13:00 hrs. The afternoon classes were rounded off with another prayer at 16:00 hrs. Then serious playing went on in the streets.

The profession of schoolmaster or mistress was considered socially low. Both could however aspire to getting a special diploma for teaching psalm melodies.

In the margins of educational practices some additional teaching was done by 'beguins'. These were Roman Catholic, unmarried women, who performed social services in town without minding the religious background of families. They lived in the local Begijnhof or Beguinage. (See yellow Delft Artists & Patrons, section Monuments)

5) Latin school.

The Latin school was considered proper for the children of the upper crust. One was admitted to Latin school if one had mastered reading and writing elsewhere. The Latin school was founded by monks in the late middle ages and the school classes were divided into five separate age groups which were followed one after another, consecutively numbered 7th, 6th, 5th, 4th, 3rd class, after which one was considered ready for university. In the period 1602-1667 the total annual number of enrolled paying pupils in the Delft Latin school was between 60 and 100, plus a group of non-paying pupils.

For the town elite a Latin schooling was desired, but private tutoring was considered even superior. See wealthy patrons in the yellow list Delft Artists & Patrons.

In 1591 the school teacher D. A. Valcooch [of the proverbial falcon eye] published rules for Dutch school teachers, Regel der Duitsche schoolmeesters, which was a list of articles to be posted in school. The text promises a sound beating for a number of regular offences. One may be sure this school masters knew of the common misbehaviour of his pupils. Beatings were common.

" He

who does not take off his cap for a man of honour / Die zijn muts niet afneemt voor een man van ere,

who just walks about yelling, cursing swearing / and die daar lopen krijten, vloeken en zweren,

who walks the streets wild and indecent / die wild en onzedig lopen langs de straten,

who plays for money, books or talk in lies / die spelen om geld, boeken of leugenen praten,

who throws stones at someone's ducks and pesters animals / die der lui eenden smijten en beesten jagen,

who does not comply to please others / die niet en doen dat de anderen behagen,

who boasts with knives, rips out hair / die met messen pochen, in 't haar plokken,

who walks the fields, jumps through straw with sticks / die in't veld lopen, door 't hooi springen met stokken,

who stays home against the advice of masters and parents / die buiten meesters of ouders raad thuis blieven,

who steals money, books, pens and paper like thieves / die geld, boeken, pennen, papier nemen als dieven,

who bathes in the nude, who walks about in peas and carrot fields / die naakt baden, in erwten, in wortelen lopen,

who fights within church buildings / die in de kerk rabouwen,

or buys candy / of snobberij kopen

who does not say grace at he table ['Lord bless these foodstuffs'] nor say prayers and praises in the morning and at night / die zijn benedictie [het gebed 'Here zegent deze spijzen'] niet over tafel en lezen, noch 's morgens noch avonds niet bidt geprezen,

who tears the book, or spoils the paper / die 't boek scheurt, of verrabbelt [beklad] zijn papier,

who call each other nicknames here / die malkanderen geven toenamen hier,

who throw their food to dogs and cats / die zijn eten werpt voor katten en honden,

who do not want to hand in what they found within the school / die niet willen weergeven wat zij in school vonden,

who spits in someone's drink or treads on someone's foodstuff / die in d' anders drinken spuwt, of op zijn eten treedt,

who tells school secrets and does not keep mum / die uit de school klapt en niet heelt 't secreet,

who does not immediately tread and spread on snot or spit which has landed on the floor / die speeksel uit de neus of de mond, met de voeten niet uit en treden terstond,

who walks home by way of the ramparts / die op de wallen lopen als men gaat naar huis,

who throw each other with snot, fleas, lice / die malkanderen bewerpen met snot, vlooien en luis,

who does not walk decently to and from church / die niet zedig lopen naar de kerk of daarvan,

who throws bits or basket or cans to eachother / die malkander smijten stukken, korf of kan,

that kind of pupil - who does not live by these rules will be beaten with two flat beating bats or will get a thrashing with the rod

/ wat scholiers deze voorzeide punten niet onderhouden zullen twee plakken hebben, of zich met de roede klauwen." (Spies, p. 20).

Poor children and orphaned children were decidedly out of luck. For them, child labour was normal far before the age of ten, and their education was ill guided by the workshop masters. In Delft children from the orphanage were put to work in a textile shop and their work situation there was appalling; many children died. The Delft city governors noted this but did nothing about it.

A painting by Jan Steen of a schoolmaster at work is in the National Gallery, Dublin.

Note: Photo Copyright Rijksmuseum Foundation. The Rijksmuseum has graciously assisted in this project Digital Home of Johannes Vermeer. The author was given permission to make a selection in the vast photo archive and this material has been made available by the Rijksmuseum.

Literature E.P. de Booij, 'Het onderwijs in Delft van 1572 tot het midden van de 17e eeuw' in Exhibition Catalogue, Prinsenhof Museum Delft, entitled 'De Stad Delft, cultuur en maatschappij van 1572 - 1667', pp. 112-120.

A.Th. van Deursen : Mensen van klein vermogen, het 'kopergeld' van de zeventiende eeuw. Ooievaar / Promethus, Amsterdam, 4e druk 1999.

Marieke van Doorninck en Erika Kuijpers, De geschoolde stad: Onderwijs in Amsterdam in de Gouden eeuw. Amsterdam, Historisch Seminarium, 1993.

José de Kruif, Liefhebbers en gewoontelezers, Leescultuur in Den Haag in de achttiende eeuw, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 1999, p. 94.

Marijke Spies, Des mensen Op-en Nedergang, literatuur en leven in de Nooordelijke Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw. Bulkboek Amsterdam/Barneveld, 2nd ed. 1985.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.