Provenance from Russia: the official plundering by state agencies of Russian museums, notably the Hermitage, in 1928-1933

Provenance from Russia: the official plundering by state agencies of Russian museums, notably the Hermitage, in 1928-1933 Provenance from Russia: the official plundering by state agencies of Russian museums, notably the Hermitage, in 1928-1933

Provenance from Russia: the official plundering by state agencies of Russian museums, notably the Hermitage, in 1928-1933Fritz Mannheimer’s purchases via the art trade from Russia, circa 1928-1933

Article in PDF file, with notes: Mannheimer PDF Hermitage

Outstanding art tours in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

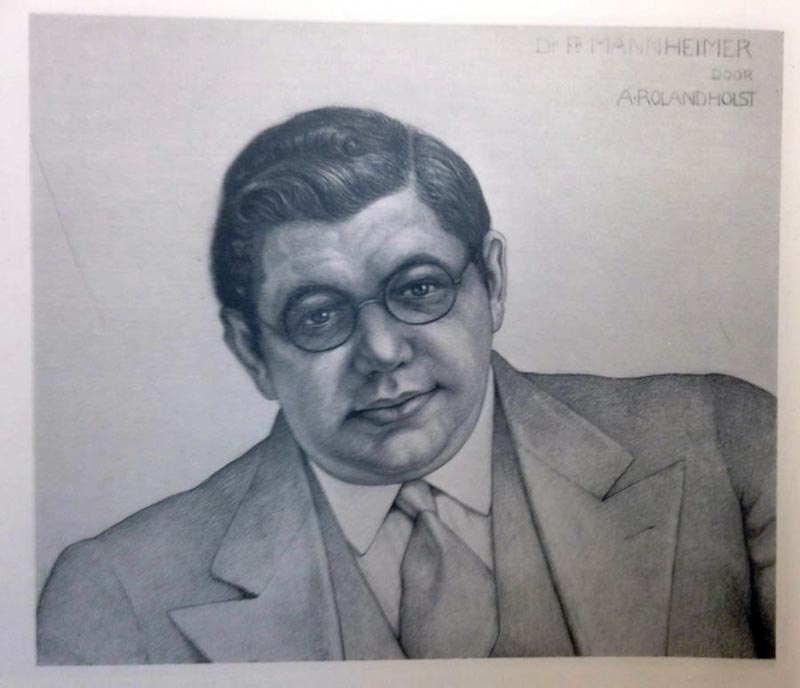

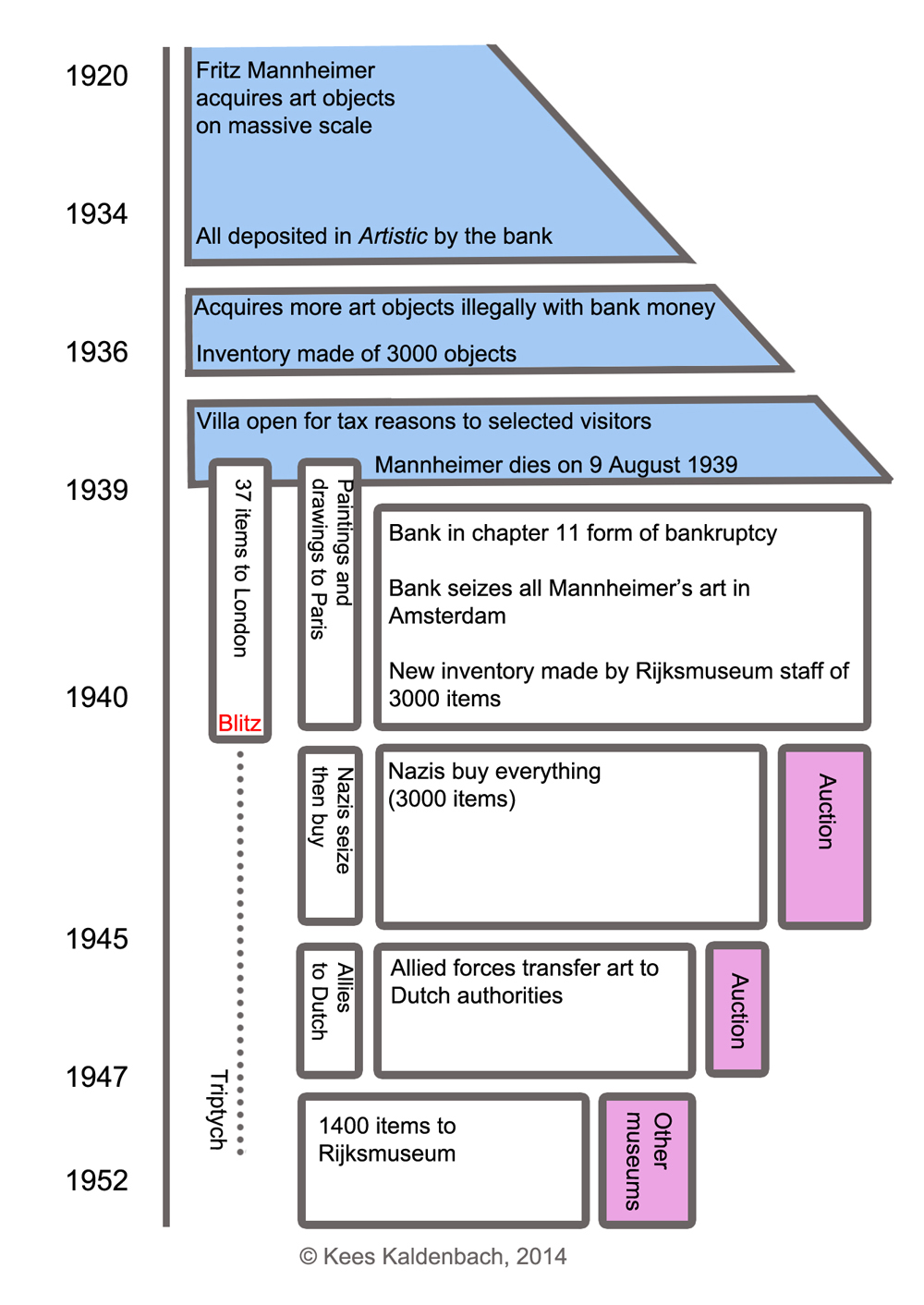

In 1952 the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam was vastly enriched with 1400 objects from the estate of the Amsterdam Jewish banker Dr Fritz Mannheimer (1890-1939). During his years in Amsterdam as a banker, from 1916 to 1939, Mannheimer purchased 3000 high quality objects of applied art and fine art. The complicated story of acquisition, the enforced Nazi purchase, recuperation and distribution has been discussed in my earlier article, see web site. About 1/30th of this treasure, some 100 objects, were purchased, through intermediaries, in Russia around 1930.

This article attempts to answer these questions: Which art dealers, advisors or intermediaries did Mannheimer employ for buying from the Soviets? And which objects now in the Rijksmuseum originally stem from what collections in Russia?

Post-revolution art dealers and art auctioneers

Post-revolution art dealers and art auctioneers

Immediately after the 1917 revolution, the Soviet state was in upheaval and the government initially allowed spontaneous violent attacks by angry mobs on property of the upper class. Then a law was issued in October 1918, nationalizing all private property, whether belonging to nobility or private citizens; even property belonging to institutions and churches was seized.

All of this property had to be itemized and registered by sending complete inventory lists to a new office called the Antikvariat. It is known how this branch operated, but its archive was lost. For selling the goods, in trade with foreign countries, Antikvariat worked with a small number of art traders as intermediaries. In order to optimize selling, specific markets were highly targeted. Dutch master paintings were mainly exported to Holland. The most expensive art objects went to buyers in England and France and initially ‘emotionally charged’ objects relating to the late Czar’s family went mainly to the USA.

In an effort to serve the revolutionary fervour at the art and education front, registry was also started of all museum property by Narkompros, a central office working on re-distribution of art works. The ideology was: putting art objects in the optimal building in Russia for the purpouse of teaching, for ideology and for ‘best use’. Between 1927 and 1933 the Soviet authorities decided to give this idea of ‘best use’ a new twist: large-scale sales of fine art and applied art objects from museums were sold abroad in order to raise funds, mainly used for industrialisation, for machinery for agriculture and for oil production. The slogan was: art for tractors. Initially museum-quality objects were kept safely within Russia. In the next step, the thin wedge of seizure was moving in: Museum quality objects were also sold, and if lucky, the original owning museum would receive 25% of the value. The Antikvariat office first operated abroad through agents who organized a sale in London in 1917. These were quite shady outlets of art. Soon the Hermitage became a transfer, selection and valuing point for mountains of fine art and applied art, removed from elsewhere in Russia.

Few facts about an art dealer selling Russian art to Mannheimer are now clear; from archival sources, one known trader is the art dealer firm Van Diemen, active in Berlin and in Amsterdam. He sold an oil painting by S.J. van Ruysdael, View of a River and a Boat. It was bought in 1930 by Van Diemen in the Hermitage, and sold in 1933 to Mannheimer.

A second likely art trader used by Mannheimer is the German auction firm Rudolf Lepke, which had officially gained buying authority in Russia in 1923. Hans Karl Krüger, their local agent in Russia, and trade partner in this firm, handled art requests from the West. A large amount of Russian art objects was offered in the November 1929 sale by Lepke in Berlin. This was the first highly visible and famous (or infamous) sale of seized Russian goods. Emigrated former owners vehemently protested when their property came up at auction and started lawsuits, but in the end to no avail. Mannheimer, being German, would have received the sale catalogue and would have used Lepke’s firm. Art objects bought by the Lepke firm in Russia had been wrapped and crated in Russia, then taken to Leningrad harbour and then by ship either via Stettin or Hamburg, the cargo to end up in Berlin. From the moment the goods left Leningrad the auctioneer and buyers had to consider their shaky legal ownership, and thus high risks.

The traders below are possibly, but less likely, to have been involved for Mannheimer’s acquisitions. A well-connected art trader was Franz Zatzenstein [originally Catzenstein], who later renamed himself Francis Matthiesen. Matthiesen’s agent Mansfield was posted in the Hermitage. Mr. Matthiesen had further ties with the Colnaghi firm (acting agent Gutekunst) and the Knoedler firm (acting agent Charles Henschel). The high-volume buying around 1930 by Calouste Gulbenkian and Andrew Mellon resulted in the end in the vast collection of the Gulbenkian museum in Lisbon; the Mellon paintings served to jumpstart the National Gallery, Washington DC. See annex.

Joseph Duveen also bought objects, including furniture from Russia. One piece went to Mannheimer, and from there to the Wrightsmann Collection, ending up in the MMA, New York. Archival sources show that Mannheimer was his client.

The RKD files also name art collector C.J. van Aalst (1866-1939) as a friend of Mannheimer’s.

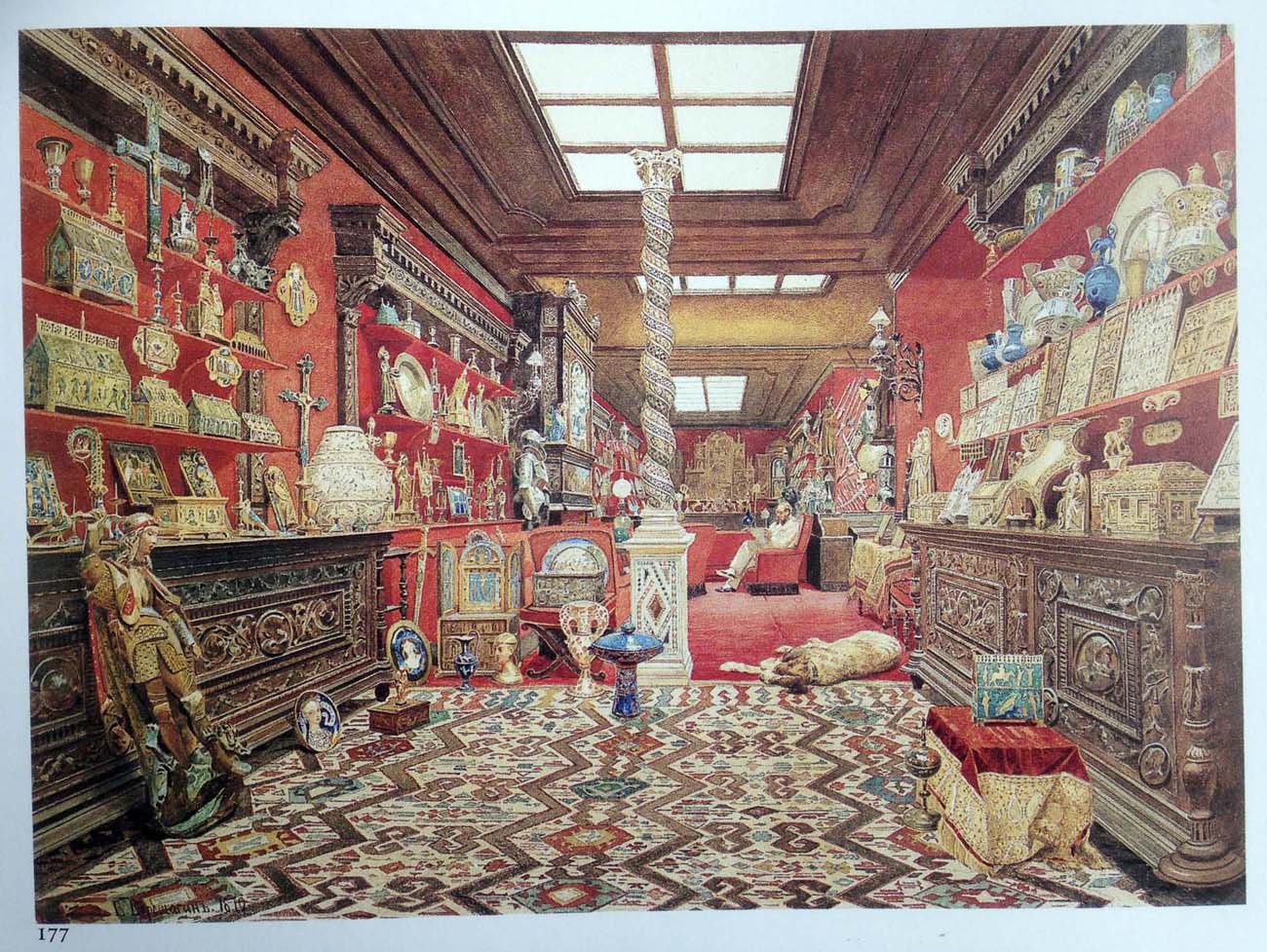

(Caption: one of the over-filled showcases at the Mannheimer home, with objects bought in Germany and Russia)

Rijksmuseum as buyer

In 1931 for f 156.000, the Rijksmuseum had bought from the Hermitage, via the Colnaghi firm, two large portraits by Anthonis Mor. They show the English trader Sir Thomas Gresham (SK-A-3118) who was stationed in Antwerp and had banking business in the Republic, and that of his wife (SK-A-3119). Author P. Hecht in his book 125 jaar Vereniging Rembrandt mentions another purchase sum: f 236.000,- for the two paintings.

A more important deal was however struck in 1933 when the Rijksmuseum gained two Rembrandt paintings:

A more important deal was however struck in 1933 when the Rijksmuseum gained two Rembrandt paintings:

1. Rembrandt’s Titus (SK-A-3138) which was bought in 1933 from the Pushkin museum of fine arts in Moscow and

2. Rembrandt’s Peter’s Denial (SK-A-3137) initially from the Hermitage, afterwards temporarily moved to the Museum of fine arts, Leningrad / St. Petersburg. This painting has hardly been on view in the Rijksmuseum galleries for the last 20 years.

Financing of the purchase of these two paintings for a total sum of f 800.000 was partly arranged through a loan from a Pension fund of Dutch Colonial employees and partly by a donation from the Rembrandt Society fund to celebrate their 50th anniversary. Van der Ham, in his history of 200 years Rijksmuseum describes how paying back this purchase loan caused a 40-year lasting stress hole in the annual Rijksmuseum purchase fund.

The painting Rembrandt’s Peter’s Denial is described by the Hermitage as having been a crucial painting and a grievous loss; it is now exhibited in the Dordrecht Museum. Rembrandt’s Titus has always been on show in the Rijksmuseum.

The painting Rembrandt’s Peter’s Denial is described by the Hermitage as having been a crucial painting and a grievous loss; it is now exhibited in the Dordrecht Museum. Rembrandt’s Titus has always been on show in the Rijksmuseum.

As a result of the wholesale dumping in the West of such large amounts of gold, precious stones, fine art and applied art in the West, market prices continuously tumbled down, and the gains by the Russian state did not bring in the cash as planned. Finally in 1933 a staff member of the Hermitage became again highly alarmed when spotting a new export list document in the Antikvariat office containing plans for export of yet another series of important works of art. In a protest letter sent with utter trepidation, Stalin was requested to stop all art sales. Stalin agreed.

This was the balance of the damage done: from 1928-1933 the total number of art works exported included 59 masterworks, 350 very important paintings and 2471 works of fine art. Plus a vast number of seized precious and semi-precious stones, applied art objects, silver and gold objects.

..

This work is on long-term loan to the Museum in Dordrecht. There it represents the link with Rembrandt students and co-workers from that town.

Mannheimer objects with Russian provenance

With hindsight, Mannheimer was just a small-time buyer in this field. His purchases from Russia comprise of no more than 1/30th of the 3000 works of art are listed in his inventories in 1936 and 1940. Postwar, in 1952, the Rijksmuseum registry has received the lions’ share, 1400 Mannheimer objects. When filtering with the key word ‘Hermitage’, a list shows 89 varied objects. However, apart from the Hermitage there were more Russian sources for art treasure. When searching through the several Mannheimer inventories the total sum exceeds 100 items.

Where did Mannheimer actually buy? It has been theorized that specialized art dealers sent him multitudes of objects to judge these at his leisure at his villa.

He lived immediately south of the Rijksmuseum, and it is likely that he would primarily have also used the antique trader shops at the Spiegelstraat and Spiegelgracht area just north of the Rijksmuseum. No Mannheimer purchase ledgers are known in archives and no sources of correspondence are known either. Neither do we know whether he also purchased anything during his international travels from 1916 to 1933. He is likely to have visited Berlin and is known to have visited Romania. After 1933, being a Jew, he may not have felt entirely welcome travelling and doing business in Germany. He probably was not allowed to travel and trade at all inside the Soviet area.

Did Mannheimer hire art experts and art advisors? Seeing he spared no expense in purchasing, he may have marshalled the help of the very best art historian and dealers to gain advice and to hunt for and pry loose desirable objects. One name readily comes up: the 1936 inventory of Mannheimer’s holdings of all 3000 items was made with the expert help of art historian Otto von Falke (1862-1942) who likely stayed as a guest for many months in a room in Mannheimer’s villa. Some of the objects listed in the Rijksmuseum inventory (such as the gold Triptych reliquary) had already been catalogued by Von Falke in Berlin decades before that. He may thus have been Mannheimer’s key advisor and collaborator.

According to Heuß (2000 and 2001) who has studied the Nazi photo album books and lists of art objects now in the State archive in Koblenz, other Russian sources for Mannheimer paintings were these mentioned below. Some objects ended up in the Rijksmuseum, some elsewhere.

Russian provenance lists of Rijksmuseum objects stemming from:

1. Hermitage

2. Basilevski collection, Petersburg

3. Great Gatchina Palace

4. Kremlin fortress in Moscow.

5. Antoniev Monastery in Novgorod

6. Stieglitz museum, now Applied Art Museum, St Petersburg

1. Objects from the Hermitage

1. Objects from the Hermitage

The now most celebrated object stemming from the Hermitage is the life-size marble Falconet statue of a young boy, ‘Amour Menaçant’ bought in 1933 by Mannheimer for FF 1.250.000.

Probably also indirectly, Mannheimer purchased five paintings, among these: S. v. Ruisdael, Ferry on a River, 52 x 80 cm. 1930 first sold to Van Diemen, likely sent to the Amsterdam branch, then to Mannheimer in 1932. ; P. Wouwerman, Pulling a Cat Tied to a String (in German: ‘Katzenziehen’) 76 x 96 cm. Bought 1932 from an unknown dealer.

This purchase list shows that Mannheimer was a relatively late buyer for Hermitage paintings, but the list of five may not be exhaustive because Mannheimer is known to have bought and again sold art objects.

A list of applied art objects from the Hermitage can be gathered from various Mannheimer inventories. Alphabetically listed, the Rijksmuseum owns the following sets from the Hermitage: Crystal Water Jugs; Chalice; Bocal; Ink stand; Meissen Chocolate drinking Set of 25 parts, including painted cups with orange-red background. (BK- 17402-A to X) plus related Jugs, with assorted Tea Pots, Boxes; Meissen Cups and Bowls (BK-17402-H-1); Meissen Tea Set (BK-17017); five decorated Meissen Vases; two Notebook Covers; a Mirror; silver Sauce Jugs (BK-17021-A and B); three Snuff Boxes (incl. BK-17144); four small art Objects; six Pendants; a small Voltaire Statue by Houdon (BK-16932).

Also purchased by Mannheimer but lost in the 1940 London Blitz were these Hermitage items: a 16th C. jewel showing Acteon; a prayer book with scenes of birth and resurrection of Christ; a manuscript on vellum with 12 miniatures, belonging to Queen Anne of Brittany; five gold boxes including an exceptionally large one; Amor with torch; a ‘chasse’ box in Limoges enamel, champlevé with religious images; a large miniature, showing the Schowalow family, 1781. A bronze statue by Donatello survived the Blitz unscathed, came on the market and was bought by the Rijksmuseum in 1960.

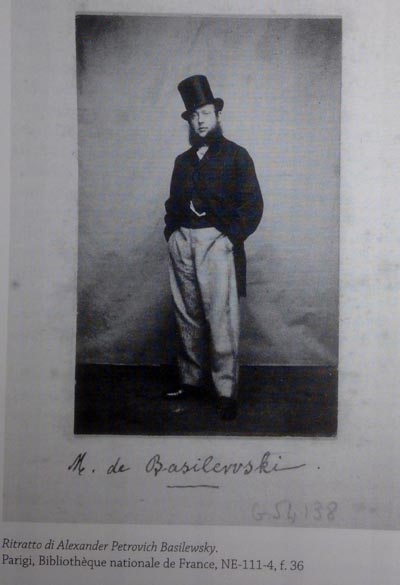

2. From the Basilewsky collection, Petersburg. Alexander Petrovich Basilewsky (also spelled Basilevsky, 1829-1899) resided in Vienna, Florence and finally Paris where he settled in 1860. From his art gallery in his Parisian home a watercolour was made (see Fig 1). His collection was about to be auctioned off in Paris when Tsar Alexander III bought the entire collection in 1885 for FF 6.000.000 to be placed in the Hermitage. Much later, around 1930 the Hermitage also served as a clearing and sorting institute for seized goods. Although parts have been sold off, much of the Basilewsky collection is still in the Hermitage.

2. From the Basilewsky collection, Petersburg. Alexander Petrovich Basilewsky (also spelled Basilevsky, 1829-1899) resided in Vienna, Florence and finally Paris where he settled in 1860. From his art gallery in his Parisian home a watercolour was made (see Fig 1). His collection was about to be auctioned off in Paris when Tsar Alexander III bought the entire collection in 1885 for FF 6.000.000 to be placed in the Hermitage. Much later, around 1930 the Hermitage also served as a clearing and sorting institute for seized goods. Although parts have been sold off, much of the Basilewsky collection is still in the Hermitage.

Mannheimer bought the following objects from the Basilewsky collection: The top part of a Bishop’s Staff (BK-17203); an Elk’s Antler dating from 1000-1100 (BK-16990) ; a group of Aquamaniles (BK-16911, BK-16912); a Pyx, or Eucharistic dove, a bird-shaped box for keeping the Holy Host (BK-17205). A silver Reliquary Bust of St. Thekla (BK-16997). A similar silver Bust of St. Ursula was bought in 1955 from the Rijksmuseum, by Basel to be placed in the Basel Historic Museum ;

====

Image above: Fig 1. V.P. Veretshchagin, Prince Alexander Petrovich Basilewsky among his collection, 1870. Watercolour, 57 x 77.5 cm. State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Inv. nr 45878. We see the Elk’s antler on the right, and a reliquary bust on the floor to the left. The palace was on the avenue formerly known as ‘Avenue Roy de Rome’ (? now called what?), by Rue Pauquet.

=== === ===

3. From the Great Gatchina Palace, which was the Czar’s favourite family residence: four bird-shaped Meissen figurines, including two Seagulls (BK-17499-A+B) and two Eurasian Bitterns (Botaurus stellaris), (BK-17498-A+B). Lost in the 1940 London Blitz were these additional items: a pair of ‘early Dresden’ (= Meissen) Parrots on trees plus another Meissen pair of Bitterns.

4. From the Kremlin fortress in Moscow. For Mannheimer it was the source of nine objects, mostly 16th Century, some of them silver. The Rijksmuseum has these objects: an extravagant Nautilus (BK-1958-44); a Beer Jug in silver, partly gilt (BK-17003); Glass Beaker, framed in silver (BK-17134); a Festive Dish (in German: Prunkschale) in crystal, on a foot (BK-17132); furthermore a Goblet with Lid (BK-17128); a Flagon in crystal on a low foot (BK-17120).

Lost in the 1940 London Blitz, was a large golden Tankard by Jamnitzer; a Serving Dish (‘Deckelpokal’) with a tree trunk and a nude young boy, made by Ludwig Krug in Nurnberg. See Mannheimer art collection, nearly entirely perished in the London Blitz

The Rijksmuseum does however own the most famous object by Jamnitzer, bought from Rothschild in Frankfurt.

5. Antoniev Monastery / St Anthony Convent in Novgorod.

For Mannheimer it was the source of a Gospel Book front cover, Christ crucified, between Mary and John (BK-17204). The Nazi inventory however lists two books and a fancy Pyx in the shape of a dove (a pyx is used by the Roman Catholic Church, usually a simple small round container to carry the Holy Host communion wafer). This one is not identical to the before-mentioned one (BK-17205).

6. Stieglitz museum, now Applied Art Museum, St Petersburg was the source of three Tobacco Rubbing Graters in boxwood, used for grating snuff tobacco. (BK-16993; BK-16994; BK-16995).

=== === ===

Annex 1: Art traders active in buying soviet art objects

Mentioned above were the art firms Van Diemen, Matthiesen and Colnaghi.

Another art trader active in Russia was Stepan M. Mussuri who obtained the right in 1929 to buy objects (with the exception of museum quality treasures) from private clients, whom he paid well and on the spot.

On behalf of the Nazis, the main buyers in Russia were the French trader Etienne Nicolas and the chief buyer for the planned Linz Führermuseum project, Karl Haberstock. It is clear that Mannheimer, being anti-Nazi, kept his distance.

From 1928 on huge sales were organized in the west, bypassing the main foreign intermediaries listed above. Flooding of western markets with Russian treasure caused a dramatic drop in prices and the volume was therefore cranked up. In 1928 the Hermitage yielded 859 works of art and the next year 17.335 works of art. Part of these may have come from outside sources and were processed by Hermitage staff. In a sly way the Hermitage staff selected second-rate and third-rate objects originally from the Hermitage, leaving their excellent works of art untouched. The hasty selection process often took just 20-30 seconds per item shown. In a backlash, buyers in the West protested at the low quality of the works of art offered. They wanted masterworks. Those museum staff members in Russia failing to cooperate were arrested and punished.

=========================

The first wealthy buyer to arrive as was the pro-communist U.S. citizen Armand Hammer who from 1921 was active in Russia, starting as an importer of grain and exporter of industrial raw materials. He from the started art purchases in 1928.

For a number of years the preferred wholesale art buyer in Russia was oil tycoon Calouste Gulbankian, then residing in Paris. Between 1928 and 1930 he made four different agreements with the Antikvariat. In the last one a vast number of objects were sold to him; this fine art and applied art ended up in his museum in Lisbon.

In 1931 the most painful and grievous loss took place in the Hermitage, where 21 of the very best of the paintings were secretly exported, bought by the U.S. Secretary of finance Andrew Mellon for a total price of $ 6,654,000. Everything was arranged quietly, out of publicity. In 1937 all of these masterworks were donated to a brand new institution founded by Mellon, the National Gallery in Washington DC. Initially, Mellon’s shopping task was made easy by reading the 1923 Hermitage catalogue published in Munich, which included inventory numbers. On behalf of Mellon, the final quality selection in the Hermitage was carried out by Charles Henschel of the Knoedler firm.

Key Hermitage works also went to museums in Melbourne and Philadelphia and a painting by Jan van Eyck went to the Metropolitan Museum of art; the New York Times published this astounding sale on 4 November 1933.

After the Soviet sales were completely halted in 1933, one could continue. U.S. Ambassador Joseph Davies and his wife Marjorie Merriweather Post were still allowed to buy and export objects. They made liberal use of their privilege. Their vast Russian collection is now in Washington, in the Hillwood Estate, Museum & gardens, northwest Washington, D.C.

Albert C. Barnes, collector from Philadelphia also bought Impressionist paintings from Russia, many pried loose by state offices from private collectors.

Semyonova and Iljine, pp. 260-265; Solomacha, p. 52. See also http://www.colnaghi.co.uk/sites/default/files/cataloguehistory.pdf, p. 37.

====================================================

LITERATURE (apart from those in the notes)

Prodannye sokrovishcha Rossii [Selling Russia’s Treasures; the original book in Russian that was published in English last year]. Nicolas Ilʹin and Natalya Semyonova. Moscow, 2000.

Treasures into tractors : the selling of Russia's cultural heritage, 1918-1938. Anne Odom and Wendy R. Salmond, editors. Washington, DC, and Seattle, 2009.

Selling Russia's treasures: the Soviet trade in nationalized art, 1917-1938. Edited by N. Semyonova and N.V. Iljine, Paris and New York, 2013.

R.C. Williams, Russian Art and American Money, 1900-40, Harvard University Press, 1980

K. Kaldenbach, ‘Mannheimer: an important art collector reappraised. History of ownership from 1920-1952: From Mannheimer to Hitler; recuperation and dispersion in Dutch museums, based on archival documents.’. (published online 2014) Full Mannheimer article 9200 words, without notes, or a separate PDF included with 130 notes.

N. Semyonova and N.V. Iljine, ed. Selling Russia's treasures: the Soviet trade in nationalized art, 1917-1938. New York, 2013. A team of scholars from the Hermitage and other experts wrote this definitive study of 362 pages; it is an expanded and reworked version of the original Russian-language book published in Moscow, 2000.

W. Bayer (ed.) Verkaufte Kultur: die sowjetischen Kunst- und Antiquitätenexporte, 1919-1938 Frankfurt am Main, 2001, p. 14.

Semyonova and Iljine, op. cit. For this study it is a telling fact that in this book the name Mannheimer is never mentioned. This implies that intermediaries have been active on Mannheimer’s behalf.

Dutch art was specifically sold by Antikvariat to the art trader Van Diemen. This art dealership had outlets in various countries and some of it ended up in the Amsterdam store, bought by Mannheimer, see Bayer 2001, op cit, p. 15.

http://www.herkomstgezocht.nl/eng/index.html consulted 15 February, 2014. In this official Dutch web site ‘Searching for provenance’ 4700 objects are listed with lost Jewish WW2 roots. An online search for Mannheimer objects showed 246 items, each with an NK number = Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit, or Netherlands Art Property Foundation. This one is listed as oil, 52 x 80 cm. inv. NK3047

E. Solomacha, see her chapter on sales from the Hermitage in Verkaufte Kultur, edited by Bayer 2001, p. 44.

Semyonova and Iljine, p. 272. See also J. Walker. Self-Portrait with Donors: Confessions of an Art Collector. Boston and Toronto, 1969, p. 243. In this account, Franz Zatzenstein-Matthiesen visiting Gulbenkian’s saw paintings from the Hermitage which he just had put on his list made for the authorities, of the one hundred paintings in Russian collections, which should never be sold. Email from the Matthiesen firm, 28 February 2014.

Semyonova and Iljine, for Gulbenkian, paying low prices, pp. 260-265; see pp. 270-275 about Mellon buying for a total of $ 6,654,000.

J. Lopez, The Man Who Made Vermeers, Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han van Meegeren, Harcourtbooks, 2008, 115.

G. Van der Ham, 200 jaar Rijksmuseum. Geschiedenis van een nationaal symbool, Waanders, Zwolle, n.d. (2000), p. 265. The Rembrandt Society also provided funds.

Walker, op. cit, p. 116 mentions a letter dated 14 January 1931, from Matthiesen to Henschel,: “…tremendous dumping…”

Six separate inventories of Mannheimer objects were produced, the first in 1934 (the Artistic list); then the 1935/36 by Otto von Falke (for opening up his villa for tax reasons); the 1939-40 was made just after Mannheimers death, produced by the Rijksmuseum staff for the legal expert, E.J. Korthals Altes was appointed as trustee administrator to deal with the tangled ownership of the treasures and real estate. Subsequently in 1942 the Nazi inventory was made in cellars where all art was stored; then in 1942-1945 the Linz Führermuseum inventory exists, and finally the 1948/49 Rijksmuseum inventory exists (now in the Nationaal Archief) with descriptions of all 3000 individual objects of fine art, applied art, furniture and books. In the end 1400 items, the cream of the crop and the lion share, remained in the Rijksmuseum.

A. L. den Blaauwen, Meissen Porcelain in the Rijksmuseum / Catalogus van de verzameling kunstnijverheid van het Rijksmuseum te Amsterdam, vol. 4, Zwolle / Amsterdam, 2000, pp. 8-9. Expert dealers in Berlin were Saemy Rosenberg, Arthur Wittekind and Hermann Ball.

A. Gerigk, ‘Zwischen den Fronten, Berichte aus dem neutralen Ausland’ in Signal, 1 April 1940, available online at this authors web site.

The first inventory of the whole Mannheimer collection was made by Otto von Falke, working in Amsterdam from November 1935 to March 1936, pp. 1-400 with an index. One full copy is in the Rijksmuseum library. Another copy is in the Nationaal Archief, SNK 2.08.42, 964.

A. Heuß 2000, Kunst- und Kulturgutraub: ein vergleichende Studie zur Besatzungspolitik der Nationalsozialisten in Frankreich und der Sowjetunion, Heidelberg 2000,p. 61.

A. Heuß 2001, ‘Russisches Kulturgut in (westeuropäischen) jüdischen Sammlungen: Von den Berliner “Russenauktionen” bis zur “Arisierung” ’ in: Verkaufte Kultur: die sowjetischen Kunst- und Antiquitätenexporte, 1919-1938, Ed. W. Bayer. Frankfurt, 2001, pp. 205-206.

F. Scholten and J. de Hond, ‘The elk antler from the funerary chapel of Louis the Pious in Metz', in Burlington Magazine, vol. CLV, no. 1323, June 2013, pp. 372-380. See note 7.

See art dealer Van Diemen in http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/guides_bibliographies/provenance/dealer_archives.html Consulted 27 February, 2014.

Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, B. 323/86, Anhang zum Inventar des Führermuseums Linz as cited in A. Heuß 2000, p. 205. Katzenziehen was a popular but nasty lower class game in which the cat was hung from a string tied to the hind legs. The rider passed by and had to yank him off, and got scratched. Details in C. Hofstede de Groot, Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten holländischen Maler des XVII. Jahrhunderts, Vol 2, Esslingen 1908, p. 591. A comparable painting is ‘Pulling eel’ shown in F. Duparc and Q. Buvelot, Philips Wouwerman 1619-1668, Zwolle, 2009, cat.nr. 13.

Nationaal Archief, 2.08.42, 430, letter dated 8 August 1939 from Chenue/Rosenbaum, London to Ms Mannheimer.

Nationaal archief, SNK 2.08.42, 549, Artistic list 16, p 131. Heuß 2001, op. cit. p. 206. (spelling varies, also as: Basilevsky / Basilewski / Basilewsky. However, in the large A. Darcel and A. Basilewsky, Catalogue Raisonnee published in Paris 1874, he himself chose the spelling Basilewsky. (Rijksmuseum libray, 105 C 63). Book title: Collection Basilewsky : catalogue raisonné précédé d'un essai sur les arts industriels du Ier au XVIe siècle.

See also the exhibition catalogue l’Ermitage de Basilewski, Milan, 2013. (873 F 27).

F. Scholten and J. de Hond, ‘The elk antler from the funerary chapel of Louis the Pious in Metz', in Burlington Magazine, vol. CLV, no. 1323, June 2013, pp. 372-380.

H. Reinhardt, ‘Het borstbeeld van de Heilige Thekla’, in Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, Vol. 6 nr 1 (1958) pp.10-16.

Heuß 2000, p. 206 writes; "… A total of nine objects, mostly from the 16th Century, came in his possession. Among them a Nautilus shell///bowl in the form of an ostrich made of gilded silver, manufactured in 1600 by the Breslauer artist J. Hiller, as well as a gold-plated silver ‘berger’ of the Nuremberg goldsmith Martin Rehlein dating from the second half of the 16th Century." In German:: “..insgesamt neun Objekte, meist aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, in seinen Besitz über. Darunter befanden sich eine Nautilusschale in form eines Straußes aus vergoldetem Silber, die der Breslauer Künstler J. Hiller um 1600 verfertigt hatte, ebenso ein vergoldeter Silberberger des Nürnberger Goldschmieds Martin Rehlein aus der zweiten hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts.” Source in note 18: Bundesarchiv Koblenz, B. 323/41-42.

When googling V&A + Rehlein for the ‘South Kensington’ cup, this is considered to be Rehlein’s masterpiece.

Third party testimonials about Drs Kaldenbach

How to find Drs Kaldenbach for a home lecture:

Map of Haarlemmermeerstraat, Amsterdam. Please note this tricky situation: there is another street in town that sounds almost the same: Haarlemmerstraat. You need however to find my street, Haarlemmermeerstraat. Take tram 2 to Hoofddorpplein square or tram 1 to Suriname plein square.

Reaction, questions?

Drs. Kees Kaldenbach, art historian, kalden@xs4all.nl Haarlemmermeerstraat 83hs, 1058 JS Amsterdam (near Surinameplein, ring road exit s106, streetcar tram 1 and 17).

Telephone 020 669 8119; cell phone 06 - 2868 9775.

Open seven days a week.

Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce (Kamer van Koophandel) number of Johannesvermeer.info / Lichaam & Ziel [ Body & Soul] is 3419 6612.

E mail esponses and bookings to art historian Drs. Kees Kaldenbach.

This page forms part of the 2000+ item Vermeer web site at www.xs4all.nl/~kalden

Launched November 12, 2014. Updated 7 March, 2018.ß

Adriaen Coorte, by Quentin Buvelot, book & exhibition catalogue.

De Grote Rembrandt, door Gary Schwartz, boek.

Geschiedenis van Alkmaar, boek.

Carel Fabritius, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

Frans van Mieris, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Grove Art catalogue, book.

Vermeer Studies, Congresbundel.

C. Willemijn Fock: Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld, boek.

Het Huwelijksgeschenk (1934), boek over de egoïstische vrouw, die haar luiheid botviert.

Zandvliet, 250 De Rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw , boek + nieuwe stippenplattegrond!

Ik doe wat ik doe, teksten van Lennaert Nijgh , boek + cd

Het Rotterdam Boek, boek.

Bouwen in Nederland 600 - 2000, boek.

Hollandse Stadsgezichten/ Dutch Cityscape, exhib. cat.

Zee van Land / over Hollandse Polders (NL) boek

Sea of Land / about Dutch Polders (English) book

A full article on the large portrait of the marvellous preacher Uytenboogaard.

Artikel over Uytenboogaerd, Nederlandse versie.

Geert Grote en het religieuze Andachtsbild TEFAF 2008 art fair