Working towards a reconstruction of Johannes Vermeer's home at

the Oude Langendijk, Delft

3D-reconstructions made by industrial designer ing. Allan

Kuiper based upon reconstruction drawings by dr.ing. Henk J.

Zantkuijl in this project

developed by art historian drs. Kees

Kaldenbach,

Johannes

Vermeer and his family lived in a spacious house at Oude Langendijk

on the corner of the Molenport/Jozefstraat alleyway, from 1660

onwards, or perhaps even earlier. Some fifteen years later at the

time of his death in December 1675, Vermeer left a relatively modest

estate. In the beginning of 1676, within the legally proscribed term

of three months, the inventory was listed by a clerk working for

Notary public. Due to an

outstanding debt which was unpaid, Vermeer's trade stock of paintings

by other masters was left out of this inventory.

Johannes

Vermeer and his family lived in a spacious house at Oude Langendijk

on the corner of the Molenport/Jozefstraat alleyway, from 1660

onwards, or perhaps even earlier. Some fifteen years later at the

time of his death in December 1675, Vermeer left a relatively modest

estate. In the beginning of 1676, within the legally proscribed term

of three months, the inventory was listed by a clerk working for

Notary public. Due to an

outstanding debt which was unpaid, Vermeer's trade stock of paintings

by other masters was left out of this inventory.

In 1957 Van Peer, a Delft inhabitant who had undertaken extensive

research on Delft city history in archives, published this Vermeer

inventory in full in the art history magazine Oud Holland. In

this inventary are not only a wonderful list of objects which are

described, but also the names of the various rooms which contained

these items as well. This allows us to take a mental walk around the

house, from the forehouse to the Great Hall and the various kitchens,

to end in the studio which was located at the front of the building

on the upstairs floor. Details on how these rooms were positioned

were not avilable, and so until 2001 no serious reconstruction

drawing had been attempted (see note 4).

Lost 17th century

interiors

Lost 17th century

interiors

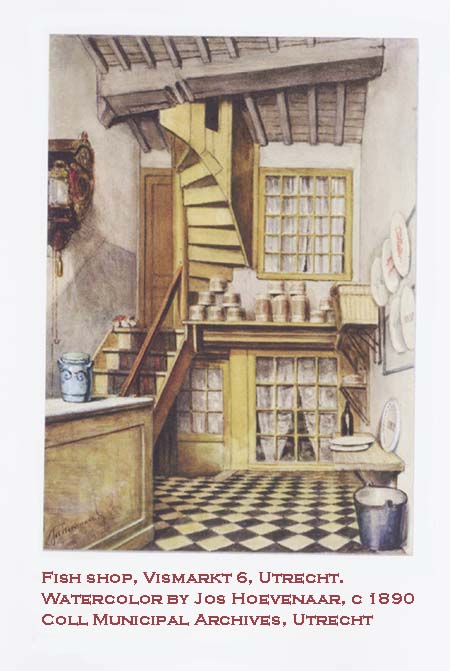

Although in The Netherlands a remarkable number of seventeenth

century facades have been handed down to us, the state of

conservation of the interiors and architectural woodwork behind the

facades is often less wonderful. No single 17th century interior of a

family home has been conserved in prime condition as far as woodwork,

separation walls, stairs, chimneys, kitchens and bedsteads are

concerned. However, during the last decades expertise in the field of

17th century homes has increased dramatically.

This knowledge is now displayed in two historical heritage sites

in Amsterdam. The living quarters of the hidden Roman Catholic church

'Onze Lieve heer op Solder' (Our Beloved Lord in the Attic) has

have remained close to their original state, and the current

historically correct furniture and objects evoke the spirit of that

era. Due to the increased expertise, not only in the field of

architectural restoration but also in several other scientific

disciplines, the Rembrandt House has recently been restored

back to an image of its 17th century state. This museum is now richly

filled with the type of objects which were once collected by

Rembrandt; objects listed for the auction of his belongings

necessitated by his bankruptcy. Within Rembrandt's studio one can now

also admire a painter's easel and painter's supplies. There is a

fragrance of painter's canvas and linseed oil.

Thanks to this increased knowledge, it is now possible to present

an architectural presentation of Vermeer's home at Oude Langendijk in

Delft. For this internet presentation a set of drawings was prepared

by the engineer dr. Henk J. Zantkuijl, formerly Associate Professor

of building engineering at Delft Technical University. This set of

drawings is presented here for the first time, along with his

technical account of his

method.

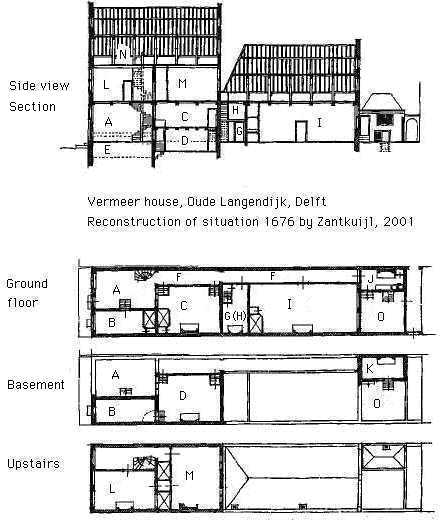

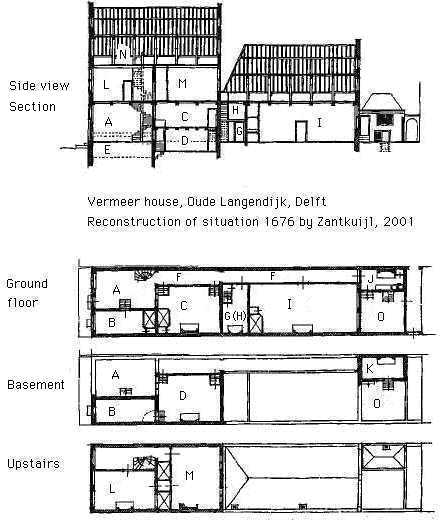

In Zantkuijl's drawings all rooms mentioned in the Vermeer

inventory have been indicated with letters.; for example,"L" marks

Vermeer's relatively small painter's studio on the upstairs floor,

overlooking the road and water of Oude Langendijk canal. Based upon

those detailed floor plans, industrial designer Allan Kuiper then

crafted a 3D model from which here a number of stills and an

Internet movie are shown.

Illusionism

Vermeer's paintings of interiors show a level of 'illusionism'

which is unparallelled given the high artistic levels in his days.

The question of whether his paintings depict existing spaces -

perhaps even rooms in Vermeer's own

house , occurs to the viewer repeatedly. In expertly applying his

incredible sense of perspective and colour, Vermeer places each human

figure in a clearly defined space created in which daylight nearly

always streams in from the left side. By closely observing and

analyzing these details, one can come to particular assumptions and

conclusions concerning the rooms and objects.

However, in the paintings we do not see images from Vermeer's

"photo album". The garments of the figures and their actions are not

of the everyday kind. With a few notable exceptions, Vermeer presents

extremely well dressed upper class, 'juffers en jonkers'

(young ladies and gentlemen) who are portrayed in a moment of silent

introspection; reading, writing, weighing, surrounded by refined and

costly objects. Vermeer lived, not in a world of high society and

nobility, but in circles of well-trained Guild craftsmen. Thus when

he depicts juffers en jonkers' in his refined interiors, then

he shows us artistic constructions, another, remote reality.

Family

life

Family

life

After his marriage in 1653 to Catharina Bolnes (ca. 1631-1688)

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) may have lived for a while in the large

parental mansion 'Mechelen' on market square, but finally the married

couple came to stay in the Thins/Vermeer home, at the north-eastern

corner of Oude Langendijk canal and Molenpoort gate. We do not know

for certain from which moment the newlyweds Catherina and Johannes

came to join Maria Thins/Bolnes (Catherina's mother, who lived from

ca. 1593-1680). The first document pinpointing the married couple as

living at that address is 27 December 1660.

Many years before, Vermeer's mother in law had separated from

Reynier Bolnes (d. 1673) after a particularly bad marriage.

At the separation she successfully claimed her fair share of the

property. Especially the land holdings made her a well-off woman. She

left Gouda and moved to Delft into the house which had been bought

one year earlier by her brother Jan Thins.

In

1653 her daughter Catharine Bolnes married Johannes Vermeer. Due to

this marriage the painter, himself son of a silk-satin

(caffa)-weaver, inn keeper and tradesman in painting has risen

very fast from a class of lower artisans to the social and financial

middle strata of Delft urban society. Vermeer researcher and author

John Michael Montias has made an estimate of the combined annual

income in the Thins/Vermeer family, which squarely puts this family

in the urban middle class.

In

1653 her daughter Catharine Bolnes married Johannes Vermeer. Due to

this marriage the painter, himself son of a silk-satin

(caffa)-weaver, inn keeper and tradesman in painting has risen

very fast from a class of lower artisans to the social and financial

middle strata of Delft urban society. Vermeer researcher and author

John Michael Montias has made an estimate of the combined annual

income in the Thins/Vermeer family, which squarely puts this family

in the urban middle class.

Vermeer paintings show little of the bustling of the busy family

life of his large nuclear family. On a day-to-day basis Catherina

Bolnes must have been very busy with her practical and domestic

affairs. Assisted by a maid, she took care of the children, ans she

must have knit, sewed, washed and mended clothes, also every day she

cooked and kept the household in good order. She became pregnant a

great number of times. In 1676, when Catherina Bolnes just turned

widow, she had eleven living children. Given the number of

burial entries we know that since her wedding day in 1653 she had

given birth to a total of fifteen

children, four of which died young. This total number of births

and this number of children surviving was exceptionally high within

the Republic of the United Provinces. Here, in circles of artisans

and the urban middle class a family with two or three children was

considered normal. (See my chapter on midwives and childbirth

in the seventeenth century). Despite the more than reasonable income

in the Thins-Vermeer home, actually feeding so many mouths and

clothing all of these growing children must have been a formidable

task.

Scenes of refined young women and men in meditative poses were thus not part

of daily life. The lower female servants are known from a few details of paintings

only. Regarding the Milkmaid one may however think of the maid Tanneke Everpoel

who lived in the Thins/Vermeer house for a number of years.

Vermeer's total oeuvre of about 35 paintings may be well

taken in totally and by the sheer visual force it invites close

looking and comparing. In the course of time one recognizes recurring

items such as chairs, garments, tapesties,

paintings-shown-within-paintings, pearls and some other objects can

be recognized in a number of sizes and varieties. A number of authors

of books and articles about Vermeer wished to recognize Vermeer's own

house at Oude Langendijk in Delft, mentally reconstructing it. This

very house which was purchased by Jan Thins, brother of Maria Thins,

will be referred to on this web site as the Thins/Vermeer house.

Reconstruction 1950

The author P.T.A. Swillens has reproduced a number of his

reconstruction drawings in his book 1950 book on Vermeer. Starting

from a number of paintings he drew floor plans and elevations of a

number of interiors, all hypothetically pointing to existing rooms.

He distinguishes five separate rooms, which he refers to as rooms A

to E, while stating that room A is shown in no less than eleven

separate paintings. Noticing how the light falls he also describes

how parts of the windows on the left side were blocked off by

shutters or sets of heavy curtains. Sizes were estimated by Swillens

by the assessed height of chairs and from that figure he calculated

the size of the floor with its pattern of light and dark marble or

earthenware floor tiles. Thus he came to present a series of

calculations and schematic representations of Vermeer's interiors.

However, Swillens lacked historical knowledge of domestic

architecture. He did not systematically take in to account the

position of ceiling beams and the visible thickness of the wall.

Neither did he understand the consequence of a visible or invisible

supporting wall next to the window. This last matter is of crucial

importance in assessing whether the window has been placed near the

corner of a facade wall or in an inner separation wall. The height of

the parapet (thus the wall from the floor to the window sill) is also

important. Swillens also failed to analyze the varied construction

types of windows.

Modern authors of recent exhibition catalogues and books on

Vermeer, including recent art history congress papers, have become

much more reticent in presenting drawings and elevations. This is

because experts now have a clearer sense of divergence between a

painting of a interior and the actual interiors. Sketching a possible

setup of a house is one thing but the margin of incertainty increases

when one tries to depict details within a reconstruction. Vermeer did

depict many variations in elements (such as maps and

paintings-within-paintings) of his seemingly photo-realist paintings.

From the 1960's onwards specialists became more convinced that

Vermeer paintings are not 'photographs' but painted reconstructions.

John Michael Montias reports this in 1989:

"If we assume, as I think we must, that Vermeer

represented more or less accurately the rooms and household

objects in his environment, we cannot but be struck by the way he

manipulated individual components of this reality to achieve his

ends." Montias, Vermeer and his

Milieu, p. 195.

Recently Philip Steadman published his book Vermeer's

Camera, Uncovering the truth behind the masterpieces (2001). In

it, he presents far-fetched hypotheses on Vermeer interiors, assuming

that Vermeer paintings are indeed almost like photographs. Steadman

supposes that Vermeer, within a studio seven meters wide at the front

of the Thins/Vermeer house, entered a separate dark room, a Camera

Obscura which he had built. There Vermeer would have done the

preparatory work for his paintings. At the end of this reconstruction

presentation it will become clear whether or not Steadman's

hypothesis are tenable.

A lack of expert knowledge concerning building engineering and

knowledge of historical architecture caused errors of assessment by

Swillens, Montias and Steadman. Montias, being the most productive

Vermeer researcher and is a prolific author of cutting edge

knowledge, assumed incorrectly that there were no less than 7 rooms

on the ground floor, among which the 'Great Hall'. Upstairs he

assumed - again incorrectly - one or more private rooms for Maria

Thins, the owner of the house. Montias rightly points out that her

personal objects including Vermeer's chief work 'The Art of Painting'

and her personal jewelry were missing:

they were not included in the 1676 inventory. How the separation of

goods - which stayed outside the inventory was done, either legally

or illegally, will probably never be known. As stated Vermeer's

commercial stock of paintings by other masters was kept out of this

inventory as well because of an outstanding debt.

This series of archival documents form the basis of the 2001

reconstruction by Zantkuijl of the Thins/Vermeer house.

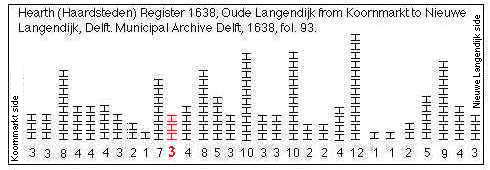

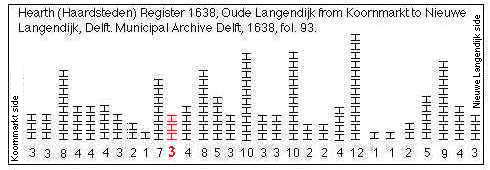

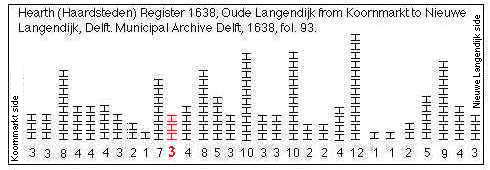

1638. The Delft Municipal Archives keeps the Hearth Tax

Register ('Register van het Haardstedengeld'), which is a tax

levied by the States of Holland on the number of hearths in each

home. From the list of houses on Oude Langendijk we learn that the

number of hearths per house varied from 1 to 12 as shown in this

graph (note 1):

By combining various elements of evidence the Thins/Vermeer house

and those of his neighbours may be pinpointed as the

red one.

According to the tax register the Thins-Vermeer home had only

three hearths in 1638. Given the list of rooms in the 1676 inventory

a large annex or addition must have taken place after the year 1638:

the Great Hall was built and a set of back kitchens. The subsequent

building history is as follows:

1641. The house and yard of what we will call the

Thins/Vermeer home was purchased in 1641 by Jan Willemszoon Thins.

This was not Maria Thins's brother Jan but their cousin Jan Thins the

Elder. The purchase sum of 2400 Carolus guilders points at a house of

an appreciable size and quality, for a modest house could be bought

in Delft at that time for 600 to 800 guilders. The Thins/Vermeer

house was situated at the north eastern corner of Oude Langendijk and

an alley called Molenpoort (the present day Jozefstraat /

Jozefsteeg). This real estate was elongated and ended at a cross

alley at the intersection of the back yards of the Thins/Vermeer

house and the back yards of the houses facing Burgwal/Turfmarkt. It

is possible that in stead of a cross alley there were initially one

or more small houses within the Molenpoort. At the Oude Langendijk

end of this alley was a wooden gate which served to stop cattle which

had escaped from the Beestenmarkt. After Jan Thins' death this

Thins/Vermeer house was inherited by his two younger sisters Maria

and Cornelia Thins. (Note 2)

1649.

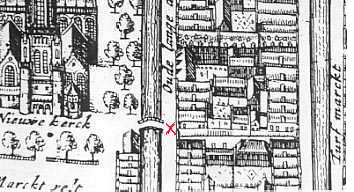

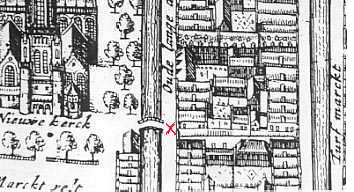

Plan of Delft, birds eye view by Blaeu. This map yields little

information on the Thins-Vermeer home, but we can get a rough idea of

the situation of this house. The preparatory drawing which served as

an image for the engraver could have been prepared prior to 1649.

1649.

Plan of Delft, birds eye view by Blaeu. This map yields little

information on the Thins-Vermeer home, but we can get a rough idea of

the situation of this house. The preparatory drawing which served as

an image for the engraver could have been prepared prior to 1649.

1676.

Inventory of household goods. This drawing by Zantkuijl, 2001,

follows the text of the Inventory of household goods and movable

goods, "huysraet ende meubile goederen" noted by an assistant

of notary public. In the Thins-Vermeer house this clerk noted the

following rooms. Letters refer to the reconstruction by

Zantkuijl.

1676.

Inventory of household goods. This drawing by Zantkuijl, 2001,

follows the text of the Inventory of household goods and movable

goods, "huysraet ende meubile goederen" noted by an assistant

of notary public. In the Thins-Vermeer house this clerk noted the

following rooms. Letters refer to the reconstruction by

Zantkuijl.

A. In the forehouse

B. on top of cellar room

C. inner kitchen

D. cooking kitchen

E. cellar

F. hallway

G. small room adjoining the great hall

H. little hanging room

I. great hall

J. back kitchen

K. washing kitchen

L. upstairs front room (studio)

M. upstairs back room

N. attic

O. the yard

To Zantkuijl's historical knowledge, bed steads, indicated on

these floor plans with an X are regularly positioned close to a

hearth and they are firmly attached to the timber and brick structure

of the house. They are not very long as those who use them sleep

sitting halfway up. Under the bedsteads, which are designed for two

adult persons, are a set of large drawers or "rolling coaches"

(Dutch: "rolkoetsen") in which children

could be stored away for the night. (see note 6) These spent the

night in somewhat claustrophobic spaces according to modern views.

The only bedstead without a hearth close by, according to Zantkuijl,

is that of the small room above the basement.

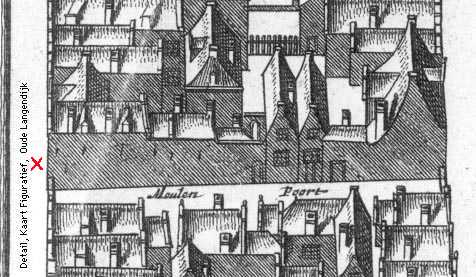

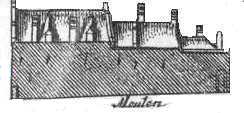

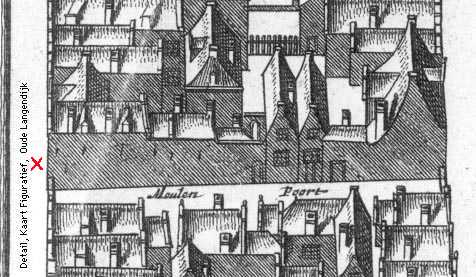

1678.

Fugurative Map (Dutch: "Kaart Figuratief"). A birds eye view of a

very large size, and of an exquisite quality, with fine detail. But

this map - just like that by Blaeu - has some limitations. It shows a

simplified impression. Within a given block between two side streets

a lesser number of houses has been depicted than the reality. But

given our present knowledge of archival material the architecture of

this Thins/Vermeer house has been carefully depicted.

1678.

Fugurative Map (Dutch: "Kaart Figuratief"). A birds eye view of a

very large size, and of an exquisite quality, with fine detail. But

this map - just like that by Blaeu - has some limitations. It shows a

simplified impression. Within a given block between two side streets

a lesser number of houses has been depicted than the reality. But

given our present knowledge of archival material the architecture of

this Thins/Vermeer house has been carefully depicted.

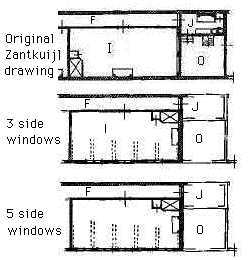

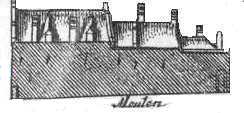

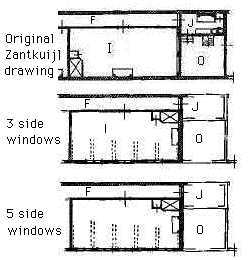

At

the Molenpoort alley we see a blind wall (a wall without windows)

with a number of wall anchors. From left to right, thus from north to

south, we see a succession of high to low building elements. At first

there is the original house, which has been dated by Zantkuijl as

sixteenth century, and next to it the annex containing the great

hall, built in the seventeenth century. Finally there are the lower

scullery buildings by the yard on the southern side. These buildings

elements have all been shown in the Zantkuijl reconstruction. The

lack or apparent lack of of windows on the alley side is remarkable.

There are a number of chimneys. If these are positioned accuretely by

the draughtsman and the engraver the very last chimney on the south

side would indicate that day light does not enter the great hall from

the southern wall but from a number of windows in the alley which

have erroneously been left out of this image. In order to allow this

alternative train of thinking to develop, Zantkuijl has also drawn

variant floor plans at my request: one variant with three windows and

a variant with five windows. The one with three windows does not work

well - given the spacing of the ceiling beams. However, Zantkuijl

feels that the initial lay out with a blind wall without windows is

the correct one. This would mean that the Great Hall was fairly

dark.

At

the Molenpoort alley we see a blind wall (a wall without windows)

with a number of wall anchors. From left to right, thus from north to

south, we see a succession of high to low building elements. At first

there is the original house, which has been dated by Zantkuijl as

sixteenth century, and next to it the annex containing the great

hall, built in the seventeenth century. Finally there are the lower

scullery buildings by the yard on the southern side. These buildings

elements have all been shown in the Zantkuijl reconstruction. The

lack or apparent lack of of windows on the alley side is remarkable.

There are a number of chimneys. If these are positioned accuretely by

the draughtsman and the engraver the very last chimney on the south

side would indicate that day light does not enter the great hall from

the southern wall but from a number of windows in the alley which

have erroneously been left out of this image. In order to allow this

alternative train of thinking to develop, Zantkuijl has also drawn

variant floor plans at my request: one variant with three windows and

a variant with five windows. The one with three windows does not work

well - given the spacing of the ceiling beams. However, Zantkuijl

feels that the initial lay out with a blind wall without windows is

the correct one. This would mean that the Great Hall was fairly

dark.

In 1676 this piece of real estate had a width of 6,70 meters and a

length of 32 meters (see the 1832 data). Given the total amount of

land between Oude Langendijk and Burgwal/Turfmarkt (see those canals

on the mas above and below) it is it hard to imagine that the two

transversal houses positioned within the alleyway at the word "Poort"

were really there. There is space for one on the 1832 map. Has the

other one been used to fill image space?

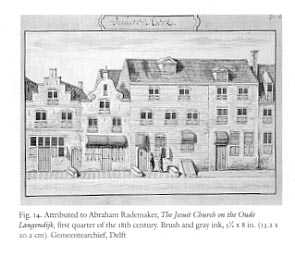

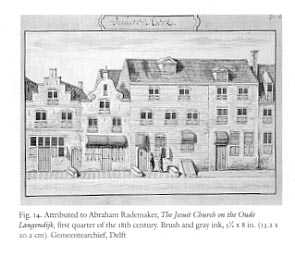

Circa

1700 ? Alas a drawing of the actual Thins/Vermeer house has not

come down to our time. In several recent publications a drawing by

Abraham Rademaker (1676/77-1735) showing the caption Jesuit church

("Jezuieten kerk") is interpreted as the Jesuit church on Oude

Langendijk canal. The exact spot on Oude Langendijk is not known to

us. The Thins/Vermeer home may be the one on the extreme right, but

may also be one or two houses over to the right, just outside the

scope of this drawing. What we can deduce from this drawing is a

series of modest houses, each one having a ground floor, an upstairs

floor, some with an extra floor, and an attic. The oddly shaped

curves above doors and windows cannot be explained here. Drawing in

Municipal Archives, Delft. Next to the Thins/Vermeer house was a

wooden gate closing off the alley. This gate kept cattle from

escaping the Burgwal/Turfmarkt catle market. Note 3.

Circa

1700 ? Alas a drawing of the actual Thins/Vermeer house has not

come down to our time. In several recent publications a drawing by

Abraham Rademaker (1676/77-1735) showing the caption Jesuit church

("Jezuieten kerk") is interpreted as the Jesuit church on Oude

Langendijk canal. The exact spot on Oude Langendijk is not known to

us. The Thins/Vermeer home may be the one on the extreme right, but

may also be one or two houses over to the right, just outside the

scope of this drawing. What we can deduce from this drawing is a

series of modest houses, each one having a ground floor, an upstairs

floor, some with an extra floor, and an attic. The oddly shaped

curves above doors and windows cannot be explained here. Drawing in

Municipal Archives, Delft. Next to the Thins/Vermeer house was a

wooden gate closing off the alley. This gate kept cattle from

escaping the Burgwal/Turfmarkt catle market. Note 3.

1733 or before. Demolition of the annex part (the Great

Hall and the scullery buildings at the back yard) of the

Vermeer/Thins house in order to make space for the new Roman Catholic

hidden church in the Molenpoort alley. See note

4.

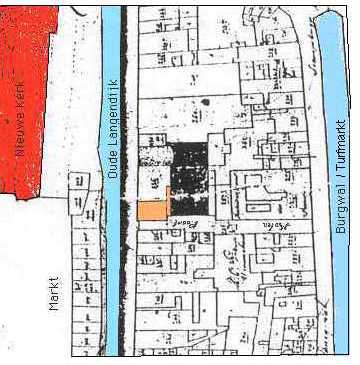

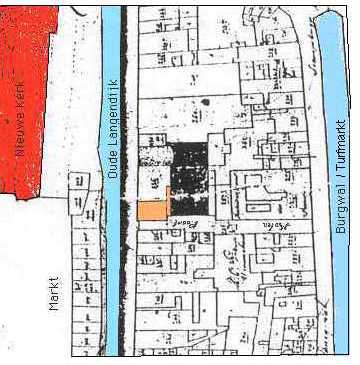

1832.

The first geographically sound map of Delft, called "Kadastrale

minuut" was published in 1832, in order to organize real estate

taxation in a professional way. (Note 5)

1832.

The first geographically sound map of Delft, called "Kadastrale

minuut" was published in 1832, in order to organize real estate

taxation in a professional way. (Note 5)

The Thins/Vermeer is indicated as a fairly short and wide house on

a piece of land of 6,70 meter wide and 12 to 13 meters long

(indicated here in orange). In 1832 the

Thins/vermeer house was owned by Nicolaas Scholtens. It then had a

registered surface of 0,0094 decimal acres ("hectare"). Clearly this

house was much shorter than the one of Vermeer's days (which was 6,70

meter by 32 meters), for the back section with the great hall has

been demolished. The piece of land which became available was sold to

one of the neighbours, who acquired a wide, probably walled garden

stretching along three houses. This broad garden is indicated in

black on this 1832 map.

In the back of each house along Oude Langendijk a piece of about 2

meters wide was retained in order to allow day light into the houses.

The real estate of the corner house seems to have a small extension

towards the back of the neighboring house.

In Vermeer's days the owner of the three houses towards the east

was Georgius van der Velde, who was the heir of Hendrick van de

Velde.

Conclusions and Propositions by Kaldenbach

1)

In 2001 the Thins/Vermeer has been

reconstructed for the first time in a

sound manner by Zantkuijl, who based himself on a set of archival

information and professional knowledge of the building history of

domestic buildings in the sixteenth and seventeenth century Dutch

Republic. (see note 4)

1)

In 2001 the Thins/Vermeer has been

reconstructed for the first time in a

sound manner by Zantkuijl, who based himself on a set of archival

information and professional knowledge of the building history of

domestic buildings in the sixteenth and seventeenth century Dutch

Republic. (see note 4)

2) Vermeer painted his oil paintings in a relatively small studio

on the upstairs floor at the front of his house. Given the available

space there could not have been a large camera

obscura of the type in which Vermeer would have sat -

according to Steadman (2001). The alternatieve space for this

instrument would have been the great hall. This room does not fit

Steadman's bill because of the apparent lack of large windows.

3) Zantkuijl has noted a number of remarkable constructive

elements in Vermeer paintings, especially concerning the kinds of

windows, walls next to windows, and walls and parapets in general. If

Vermeer did paint existing rooms in his house, then

constructive conclusions can be reached.

Zantkuijl in his separate text has tried to link the reconstructed

interior of the Vermeer house and paintings by Vermeer. See Zantkuijl's

full explanatory text.

4) The 1676 inventory is both extensive and detailed. By

constructing a model of the Thins/Vermeer house with reproductions of

similar objects, it has now become possible, after many centuries, to

visit his house and studio of the great

painter. This digital historic house can be visited by clicking on

lists and by seeing internet

movies. These are made with a zero budget in money and time and

are thus not of Hollywood standard.

5) The reconstruction presented here presents a unique chance to

imagine the shape of a lost Vermeer

painting. The Hoet sale catalogue in Amsterdam, on 16 May 1696

mentions this painting as number 5: "In which a master washes his

hands, in a perspective room, with several human beings, artful and

rare, by Vermeer" - sold for 95 guilders.

("Daer een Seigneur zijn handen wast, in

een doorsiende kamer, met beelden, konstig en raer, van dito

[=Vermeer], f 95-0.") The word "beelden" refers to human

figures not statues according to dr. Albert Blankert (in a private

message, 2000). If this lost painting showed a room within the

Thins/Vermeer home, then we can make assumptions about a possible

perspective view from one room into the next. There are some

possibillities: a view from the great hall towards the little room

(or vice versa) or from the forehouse towards a kitchen (or vice

versa). I trust Vermeer has used his 'photoshop' mode unleashed his

great powers of visual imagination.

Go to the full Menu of art history tours.

Notes

Note 1. Delft municipal archive, Hearth tax register

("Haardstedengeld"), 1638, Oude Langendijk, fol. nr 93.

Walking east from the buildings alongside Oude Langendijk from

Koornmarkt to Nieuwe Langendijk, including an odd house in an

alleyway, the list is as follows. In this chart I present note the

number of hearths, followed by a list of the owners:

Koornmarkt side

3 Arent Jacob Stopper

3 Children of Jacob Knoopman

8 Jean la Coorde

4 Cornelis Boom, timmerman

4 Widow of Dominicus Hofboom

4 Claes Claes van Swieten

3 Cornelis Pieterszoon Prins

2 Thyman/Sijmon van Slingelant

1 Thyman/Sijmon van Slingelant

7 Thyman/Sijmon van Slingelant

3 Widow of van Hendrick Claesz [here

identified as Thins-Vermeer house]

4 Hendrick van den Velde

8 Hendrick van den Velde

5 Hendrick van den Velde

3 Jonker Lambracht Boenderhorst (erroneously

transcribed by Montias)

10 Jonker Lambracht Boenderhorst

3 Pieter Gijzenburch

3 Anthony der Heyde

10 Anthony der Heyde

2 Anthony der Heyde

2 Arent Jansz. Stopper

4 Notary Public Van der Ceel

12 Willem Kittensteijn, br

(=brewer?)

1 Thomas Pick

1 Jonker Ernest Tzum (spelling ?)

2 Jonker Ernest Tzum (spelling ?)

5 Jonker Sanderling

9 De heer Van Doorne

4 De heer Van Doorne

3 Jan T. van Heere (spelling ?)

Nieuwe Langendijk zijde

In the eighteenth century the Thins/Vermeer house is owned by

Pieter Tjerk, a man who owned a great deal of real estate.

Note 2. GAD Protocollen notaris C.P. Bleyswijck, no 1914, fol 120,

20 april 1641. See also Van Peer 1968, p. 223.

Ownership by Jan Thins in GAD Huizenprotocol 326. From a now lost

foliobook the following data on taxation: Jan Thins te Gouda, reg. 3

R fol. 116 vo, is belast met 15 stuivers, 12 penningen 's jaars."

Sale of the house to Maria Thins has not been found in the

archives.

Note 3. For Rademaker see Kees Kaldenbach in the Author section.

"Abraham Rademaker (1676/77-1735); nieuwe biografische gegevens en

een verkenning van zijn getekende werk" Leids Kunsthistorisch

Jaarboek 1987. This article is also available online at my Author

section.

Note 4. In the eleventh year book of the Delft Historical Society

(Elfde Jaarboek 2001 van Delfia Batavorum), p. 60-78 is the

article by Ab Warffemius 'Jan Vermeers huis. Een poging tot

reconstructie'. On page 61 of this book which appeared in 2002 he

writes: "...until this day nobody has dared to make a reconstruction

of the entire house." Indeed at that point Zantkuijls drawings for

this web site were finished but had not yet been published.

A comparison between Zantkuijl drawings and those by Warffemius

show that they are very different: Warffemius drew the house much

narrower and his annex contains rooms which according to Zantkuijl

belong in the main structure. It is up to the reader to weigh the

merits of both sets of plans and elevations. The Warffemius text on

the 1733 renovations is nevertheless quite informative.

Note 5. I took exact measurements of the Thins/Vermeer home Oude

Langendijk from the modern atlas re-publication of the Kadastrale

Minuut. Editors: M. Claessens en R.F. Wybrands Marcussen,

Kadastrale Atlas Zuid Holland: DELFT, uitgeverij/publisher

Matrijs, Schoonhoven/Utrecht 1998. According to the publisher, the

map in question was reproduced in a scale of 1:3000. By comparison

with the best large scape map available in the Delft Archive reading

room (1:1000) I calibrated the scale of the Kadastrale Minuut Atlas

map at 1: 3076. As the reproduction of the houses reproduced on the

Kadastrale minuut is tiny there is a margin or error of a few %.

To my best estimate the width of the house appears as = 2,2 mm =

6,76 meters. Length of the house and tiny yard appeared as = 3,85 mm

= 11.55 meters. Both Montias 1989 and Van Peer (Oud Holland 1968, p

220-224) confirm that in the 17th Century the house extended much

further back, leading to a back-on back with another house on

Burgwal. In between those two was a small alleyway going east-west

leading to the back entrance of the Jezuieten schuilkerk (Jesuit

hidden church). Reckoning from the Kadastrale minuut and allowing for

the small alleyway I figure the lenght of the real estate (surface

only) on 10,4 cm x scale 3.076 = 31,99 meters, say 32 meters. This is

the maximum total length.

Note 6. Oral comunication by Zantkuijl, 2001: 'Rolkoetsen' in

which children slept under a bedstead, these are documented in the weaver's

houses which were built by Vinckboons in Amsterdam.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A

full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.

Thanks to industrial engineer and web-wizard ir. Allan Kuiper for his

wonderful navigator and 3D movies.

Johannes

Vermeer and his family lived in a spacious house at Oude Langendijk

on the corner of the Molenport/Jozefstraat alleyway, from 1660

onwards, or perhaps even earlier. Some fifteen years later at the

time of his death in December 1675, Vermeer left a relatively modest

estate. In the beginning of 1676, within the legally proscribed term

of three months, the inventory was listed by a clerk working for

Notary public. Due to an

outstanding debt which was unpaid, Vermeer's trade stock of paintings

by other masters was left out of this inventory.

Johannes

Vermeer and his family lived in a spacious house at Oude Langendijk

on the corner of the Molenport/Jozefstraat alleyway, from 1660

onwards, or perhaps even earlier. Some fifteen years later at the

time of his death in December 1675, Vermeer left a relatively modest

estate. In the beginning of 1676, within the legally proscribed term

of three months, the inventory was listed by a clerk working for

Notary public. Due to an

outstanding debt which was unpaid, Vermeer's trade stock of paintings

by other masters was left out of this inventory. Lost 17th century

interiors

Lost 17th century

interiors Family

life

Family

life

1649.

Plan of Delft, birds eye view by Blaeu. This map yields little

information on the Thins-Vermeer home, but we can get a rough idea of

the situation of this house. The preparatory drawing which served as

an image for the engraver could have been prepared prior to 1649.

1649.

Plan of Delft, birds eye view by Blaeu. This map yields little

information on the Thins-Vermeer home, but we can get a rough idea of

the situation of this house. The preparatory drawing which served as

an image for the engraver could have been prepared prior to 1649. 1676.

Inventory of household goods. This drawing by Zantkuijl, 2001,

follows the text of the Inventory of household goods and movable

goods, "huysraet ende meubile goederen" noted by an assistant

of notary public. In the Thins-Vermeer house this clerk noted the

following rooms. Letters refer to the reconstruction by

Zantkuijl.

1676.

Inventory of household goods. This drawing by Zantkuijl, 2001,

follows the text of the Inventory of household goods and movable

goods, "huysraet ende meubile goederen" noted by an assistant

of notary public. In the Thins-Vermeer house this clerk noted the

following rooms. Letters refer to the reconstruction by

Zantkuijl. 1678.

Fugurative Map (Dutch: "Kaart Figuratief"). A birds eye view of a

very large size, and of an exquisite quality, with fine detail. But

this map - just like that by Blaeu - has some limitations. It shows a

simplified impression. Within a given block between two side streets

a lesser number of houses has been depicted than the reality. But

given our present knowledge of archival material the architecture of

this Thins/Vermeer house has been carefully depicted.

1678.

Fugurative Map (Dutch: "Kaart Figuratief"). A birds eye view of a

very large size, and of an exquisite quality, with fine detail. But

this map - just like that by Blaeu - has some limitations. It shows a

simplified impression. Within a given block between two side streets

a lesser number of houses has been depicted than the reality. But

given our present knowledge of archival material the architecture of

this Thins/Vermeer house has been carefully depicted. At

the Molenpoort alley we see a blind wall (a wall without windows)

with a number of wall anchors. From left to right, thus from north to

south, we see a succession of high to low building elements. At first

there is the original house, which has been dated by Zantkuijl as

sixteenth century, and next to it the annex containing the great

hall, built in the seventeenth century. Finally there are the lower

scullery buildings by the yard on the southern side. These buildings

elements have all been shown in the Zantkuijl reconstruction. The

lack or apparent lack of of windows on the alley side is remarkable.

There are a number of chimneys. If these are positioned accuretely by

the draughtsman and the engraver the very last chimney on the south

side would indicate that day light does not enter the great hall from

the southern wall but from a number of windows in the alley which

have erroneously been left out of this image. In order to allow this

alternative train of thinking to develop, Zantkuijl has also drawn

variant floor plans at my request: one variant with three windows and

a variant with five windows. The one with three windows does not work

well - given the spacing of the ceiling beams. However, Zantkuijl

feels that the initial lay out with a blind wall without windows is

the correct one. This would mean that the Great Hall was fairly

dark.

At

the Molenpoort alley we see a blind wall (a wall without windows)

with a number of wall anchors. From left to right, thus from north to

south, we see a succession of high to low building elements. At first

there is the original house, which has been dated by Zantkuijl as

sixteenth century, and next to it the annex containing the great

hall, built in the seventeenth century. Finally there are the lower

scullery buildings by the yard on the southern side. These buildings

elements have all been shown in the Zantkuijl reconstruction. The

lack or apparent lack of of windows on the alley side is remarkable.

There are a number of chimneys. If these are positioned accuretely by

the draughtsman and the engraver the very last chimney on the south

side would indicate that day light does not enter the great hall from

the southern wall but from a number of windows in the alley which

have erroneously been left out of this image. In order to allow this

alternative train of thinking to develop, Zantkuijl has also drawn

variant floor plans at my request: one variant with three windows and

a variant with five windows. The one with three windows does not work

well - given the spacing of the ceiling beams. However, Zantkuijl

feels that the initial lay out with a blind wall without windows is

the correct one. This would mean that the Great Hall was fairly

dark. Circa

1700 ? Alas a drawing of the actual Thins/Vermeer house has not

come down to our time. In several recent publications a drawing by

Abraham Rademaker (1676/77-1735) showing the caption Jesuit church

("Jezuieten kerk") is interpreted as the Jesuit church on Oude

Langendijk canal. The exact spot on Oude Langendijk is not known to

us. The Thins/Vermeer home may be the one on the extreme right, but

may also be one or two houses over to the right, just outside the

scope of this drawing. What we can deduce from this drawing is a

series of modest houses, each one having a ground floor, an upstairs

floor, some with an extra floor, and an attic. The oddly shaped

curves above doors and windows cannot be explained here. Drawing in

Municipal Archives, Delft. Next to the Thins/Vermeer house was a

wooden gate closing off the alley. This gate kept cattle from

escaping the Burgwal/Turfmarkt catle market. Note 3.

Circa

1700 ? Alas a drawing of the actual Thins/Vermeer house has not

come down to our time. In several recent publications a drawing by

Abraham Rademaker (1676/77-1735) showing the caption Jesuit church

("Jezuieten kerk") is interpreted as the Jesuit church on Oude

Langendijk canal. The exact spot on Oude Langendijk is not known to

us. The Thins/Vermeer home may be the one on the extreme right, but

may also be one or two houses over to the right, just outside the

scope of this drawing. What we can deduce from this drawing is a

series of modest houses, each one having a ground floor, an upstairs

floor, some with an extra floor, and an attic. The oddly shaped

curves above doors and windows cannot be explained here. Drawing in

Municipal Archives, Delft. Next to the Thins/Vermeer house was a

wooden gate closing off the alley. This gate kept cattle from

escaping the Burgwal/Turfmarkt catle market. Note 3. 1832.

The first geographically sound map of Delft, called "Kadastrale

minuut" was published in 1832, in order to organize real estate

taxation in a professional way. (Note 5)

1832.

The first geographically sound map of Delft, called "Kadastrale

minuut" was published in 1832, in order to organize real estate

taxation in a professional way. (Note 5)