In the light of Geert Grote:

In the light of Geert Grote:Andachtsbilder and images of spirituality in the sacred and the profane world

In the light of Geert Grote:

In the light of Geert Grote:

Andachtsbilder and images of spirituality in the sacred and the profane world

An article by Drs Kees Kaldenbach, Amsterdam

kalden@xs4all.nl

The Christian Church and the mediaeval culture of prayer

The Christian Church and the mediaeval culture of prayer

In the late mediaeval Western Europe, surviving day-to-day life in reasonably good bodily health was a walk close to the edge for most people. Death was a frequent visitor, from the moment of birth to adulthood, as fatal diseases might come flying in and strike anytime. Temporal life was seen as short and unsure and just a valley-of-tears gateway to eternal life. Redemption and salvation were taken very seriously and faith in the eternal afterlife became the core element of spiritual life. This suffused laymen and church people alike with the hope of ascending to heaven in order to enjoy the sublime company of the saints and the divine presence. In this yearning for spiritual ascent, the church was the only mediator, and the central pivot as it held all of the keys to temporal and eternal salvation. Christians sought assistance in their shaky situating by communicating through the Holy Mother Church with Saints and with God, especially Christ. The culture of prayer, even personal prayer, was supported and enforced by the official Mother church, which exerted a tight control on doctrine. Scared of being found heretical, the faithful followed the religious rulings of the Mother church, by necessity toeing the line. Official church lines of policy and faith were published in the learned writings of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1275) and Johannes Bonaventure (1221-1274).

Generally, the use of images had long been advocated and controlled by the Church in order to properly instruct and teach the official church stance of faith to the illiterate masses. This didactic function of showing historia (meaning a series of images in a coherent set) in church buildings was supported at the beginning of the Middle Ages by Pope Gregory the Great (ca. 520-604) and this church policy would remain in force during the Middle Ages.

Thus in Western Europe a set of preferred, more or less standardized images was used. These included series of scenes revealing the Salvation, including the conception, birth, life, death and resurrection of Christ or alternatively, series of scenes from the lives of various Saints.

Embellishment and adornment of sacral spaces, including that of church buildings with visual objects for church activities was considered by many Church leaders to be a didactic necessity and therefore a worthwhile investment. These beautifying adornments included items such as liturgical vestments, vessels, but also sculpture, sometimes extended into a retabulum with many sculptures, and painted murals or movable paintings adorning the walls. All this imagery was designed to instruct but also to yield to the visiting masses a sense of elevation from the common life to the spiritual, and thus to facilitate their prayer.

According to the second Nicene council three increasing and mutually exclusive levels were admissible in prayer: 1) memoria, 2) veneration, 3) adoriation.

Memoria was the lowest level, the act of remembering of good persons and saints, and this field was least subject of confusion among laymen and thus of little worry to clerics.

A secondary, more elevated group consisted of objects worthy of veneration, meaning “the act of honoring someone, and through them honoring God who made them and in whose image they are made”. Veneration was most often expressed in prayer but could also extended in a pilgrimage, to travel and visit bodily remains of saints, or holy objects.

The third and highest level existed in adoration, which exclusively referred to “worship given to God alone”. Direct prayer to God was always considered an act of adoration, and the second Council of Nicene established a new limit on related objects: while praying before a crucifix, this physical scale model of the cross was considered just an object, not to be adored but to be properly venerated, just like an image of saints and of the Virgin Mary.

An increasingly problematic field in theology and ornament was that of a work of art showing an imago of Christ or a saint. Back in the days of Roman emperors, the image of the current emperor was widely distributed throughout the empire. As the emperor was considered a divine figure, his representation in a painting, in a bust or a statue, was considered representing his presence in effigy. Through the image he was actually represented as being there.

Later on, Christian cult images took on that same immediacy of presence and representation. Veneration of these sacred Christian cultic images became a widely popular practice, resulting in a sometimes unfortunate mixing the image and the reality behind it in the minds of the unschooled group of the faithful. This confusion of image and the reality behind it was considered unacceptable and thus became subject of concern and debate within Church.

The Church decreed that images of the Christ were to be venerated (thus not adored) as they were only physical objects. The Vera icon of Christ was however an exceptional case, as it was considered the most miraculous image of Christ. According to legend, it was received by Veronica when she wiped His face with a cloth during the Passion, when Christ was carrying his heavy cross through Jerusalem.

Images of Mary were also to be venerated and they were highly sought after, as Mary was considered as an easily approachable, embracing, caring and loving saint and therefore a pathway towards Christ.

The Mother Church, in its official writings, was concerned with the beautification of church buildings and other sacred spaces, but busied itself hardly at all with developing sacral items for use in private homes.

The Mother Church, in its official writings, was concerned with the beautification of church buildings and other sacred spaces, but busied itself hardly at all with developing sacral items for use in private homes.

Yet under the influence of teachings of the Franciscans (founded 1209) and Dominicans (founded 1215), many lay people started to feel a hunger for a personal experience of faith within the privacy of their own homes. One literary source commonly accepted by late mediaeval scholars as an official support for the use of images, and for works of art for private spaces was the letter to the hermit Secundinus purportedly written by Preudo-Gregory: If we think of The Lords Resurrection, our heart is filled with joy; if we meditate on His Passion, our heart melts with tenderness.

There are indications that a growing interest developed in obtaining these images for use in monasteries, specifically for use in the private cells of the friars, in order to facilitate their mystical uplifting of the friars towards God.

Cistercian monasteries (the first one founded in 1098) stressed the value of individual prayer and meditation, and their strictly unadorned buildings often were located in secluded places, tucked well away from the worldly sphere.

By contrast, the begging orders, especially the Franciscans and the Dominicans strove to be of service to fellow human beings in cities and thus worked in urban settings, directing their efforts to pastoral care for the town inhabitants. Their offshoots, the so called Third Orders (Tertiaries), lived according to Franciscan of Dominican rules, without being made full friar, thus satisfying a layman’s quest for ascetic life. They were often in close contact with the city population, teaching them forms of individual prayer. This education may have also stimulated an increase in public interest for images, for works of spiritual art to be used in private homes.

In this way Franciscans and Dominicans, and their Third Orders, helped to spread the deeper and more personal art of prayer. In order to focus better attention during prayer and meditation they advocated using works of visual art. This drive to self-sanctification established a growing market and as a result, religious objects were readily produced by artists’ workshops in great numbers. This production will be discussed later on.

One of the tenets stressed in the secluded Cistercian monasteries was the human nature and goodness of Christ. Around the period 1275 - 1300 the author currently known as Pseudo-Bonaventura wrote Meditationes Vitae Christi, a collection of meditations in which the reader was invited to seek Christian perfection. This method used is a constant renewal of the powers of imagination, reliving step by step the experiences of Christ and the saints by immersion and re-sensing their presence and stories. In that sense this side of Christian religion was framed in terms of a highly corporeal existence. Storytelling around religious texts flourished, and by re-framing and retelling gospel texts and the lives of Saints in new and different ways, a much more intense, emotional and colourful experience of prayer was opened up.

This way of thus ushering the soul along in its ascent to God was considered a great step forward, compared to the former basic requirements in the middle ages, when laypeople were only required to be able to recite the ‘Our Father’ by heart and also the ‘Twelve articles of Faith’, the Nicene Creed. Many church leaders applauded this drive for broadening and deepening the foundation for religious life of the laity

Andachtsbilder

One particular subset of these objects for private devotion are Andachtsbilder. The term Andachtsbild combines the German words Andacht and Bild. The latter denotes a painting, drawing or sculpture. Generally, Andacht refers to the particular function of focusing and devoting ones total attention on a subject. Andacht in a particular religious sense of the word denotes the action of focusing on a holy person or subject by the one who prays, perhaps striving for mystical union. In a specifically Christian-religious context Andacht specifically refers to devotion of the Holy Trinity, with or without the use of a concrete object aiding this form of devotion. An Andachtsbild is such a concrete object, which serves to project an inward image and may contain two subjects: the life of the Virgin Mary and the Passion of Christ, either separately or combined in one image.

In the framework of this thesis I will try to establish a tentative link between the psychological and spiritual effects on the beholders of these Andachtsbilder, aiding a link between the beholder and God, and later on I will attempt to compare the psychological and spiritual effects experienced by some viewers in the works of Vermeer.

One of the seminal texts on Andachtsbilder dates from 1927, and was written by Erwin Panofsky, who later became the ‘father’ of Iconography, with his theory of hidden symbols in works of art. In his 1927 paper he distinguishes on one hand normal history painting and representational painting, which he compares to epic texts. At the other hand he notes Andachtsbilder, which are more lyrical and dramatic by nature,

“…durch die Tendenz, dem betrachtenden Einzelbewusstsein die Möglichkeit zu einer kontemplativen Versenkung in den betrachteten Inhalt zu geben, d. h. das Subjekt mit dem Objekt seelisch gleichsam verschmelzen zu lassen.“

In translation:

“…by the tendency to allow the possibility to the observing single consciousness to a contemplative meditation within the focus of attention and give its contents a meaning, in other words to really allow a melting in terms of soul of the subject with the object.”

Andachtsbilder are thus well-defined works of art, with a given subject matter, serving a specific spiritual function and they were produced by artists working along the lines of religious and philosophical tradition of the Mother Church and great mediaeval mystical thinkers. In discussing this background of mystical and religious philosophy and practices of prayer I will present a brief outline of the prayer practice and philosophy put forward by Geert Grote and also briefly touch upon some related authors as Jan van Ruusbroec, and Thomas a Kempis. For the faithful, their methods of concentration and prayer could open up gateways for transportation of the mind, probing deeper and more intimate than usual into the layers of religious and emotional self. Moreover their ideas and writings, indirectly or directly, may have led to the emergence of Andachtsbilder.

Geert Grote

Geert Grote

Geert Grote (also known as Geert Groote as often spelled in 19th century studies) was a Dutch theologian, author and ‘preacher of penitence’. Born in the town of Deventer in the eastern part of the Netherlands in 1340, he died there in 1384. At the Sorbonne in Paris, Geert Grote studied medicine, theology and canonical law and subsequently he became canon in Aachen in Germany and subsequently made the full ascent to the religious centre of The Netherlands. There, in Utrecht he became an ambitious and wealthy scholar, living in luxury.

As a result of gradually shifting toward a more inward looking philosophy of life, in 1372 he had embraced an ascetic life, a deep felt choice also yielding from the transforming inner processes of going through a serious illness. Later on Geert Grote wrote that he was steeped in worldly interests during those Utrecht years, but his oft-cited expression of ultimate shame, taken at face value by some authors, may be taken as just an rhetoric instrument: “under every green tree and on every high hill I have been playing the harlot”, he wrote, in a variation on Jeremiah 2:20.

In developing this inner change towards the ascetic, Geert Grote was heavily influenced by the writings of the curate (assistant priest) Jan van Ruusbroec who lived in Brussels and wrote of his mystical experiences in texts infused with a deep inner feeling of the world of the human soul. In his writings, Van Ruusbroec used a visionary style, and advocated an increased awareness of morality.

In mystical writings there is a poetic relationship between those elements tentatively uttered in human words and those elements left unsaid, because language only goes to a certain extant and cannot fully embrace deeply hidden spiritual concepts.

In Deventer, Geert Grote founded the core of a particular spiritual community. He divided his own private home in Begijn street, moving into a small room for himself and offering the major part of his house to welcome a group of adult women with a spiritual focus. Their practical day-to-day work was out in society and was specifically geared to supporting school-going youths and to improve the way common people were housed. These women subscribed to house rules according to his tenets, and became known as the Sisters of Common Life. Theirs was a life of poverty, strongly contrasting with the life of luxury found in some established monasteries and church circles.

In Deventer, Geert Grote founded the core of a particular spiritual community. He divided his own private home in Begijn street, moving into a small room for himself and offering the major part of his house to welcome a group of adult women with a spiritual focus. Their practical day-to-day work was out in society and was specifically geared to supporting school-going youths and to improve the way common people were housed. These women subscribed to house rules according to his tenets, and became known as the Sisters of Common Life. Theirs was a life of poverty, strongly contrasting with the life of luxury found in some established monasteries and church circles.

Later on, perhaps in 1381, Geert Grote’s student and companion Floris Radewijnsz (1350-1400) founded a male religious group, the Brothers of Common Life (‘Broeders des Gemenen Levens’) along the same tenets.

Thus separated in two buildings in Deventer, these members shared property and daily food without actually taking the step to enter into strict monastery vows. Their concern was pastoral, taking care of religious life of the laity.

The framework of prayer practice of the Sisters of Common Life has later been labelled Modern Devotion, Devotio Moderna, in Dutch: Moderne Devotie, denoting that particular spiritual reformation movement within the 14th c. church. This movement stressed the sanctity of daily life and expressed practical wisdom of how to deal with the problems that daily life presents.

Geert Grote preached widely in towns as far apart as Amersfoort and Delft and generally did not mince words when he fulminated against renegade clerics and heretics. Alarmed with his divergence from official church tenets, the bishop of Utrecht protested against the far-reaching contents of his preaching and issued a preaching ban. Notwithstanding these obstructions from higher up, some of his prayer texts became widely known and popular with laypersons, so that they were selected and entered into many a copy of a personal Book of Hours. Visualisation and imagination were two important tools of focus in this type of prayer and meditation. Generally a window was sought for the faithful to be closer to God and to construct a way for daily life to aid that closer proximity.

Geert Grote preached widely in towns as far apart as Amersfoort and Delft and generally did not mince words when he fulminated against renegade clerics and heretics. Alarmed with his divergence from official church tenets, the bishop of Utrecht protested against the far-reaching contents of his preaching and issued a preaching ban. Notwithstanding these obstructions from higher up, some of his prayer texts became widely known and popular with laypersons, so that they were selected and entered into many a copy of a personal Book of Hours. Visualisation and imagination were two important tools of focus in this type of prayer and meditation. Generally a window was sought for the faithful to be closer to God and to construct a way for daily life to aid that closer proximity.

What may strikes us as incongruous from a modern point of view is the combination of the loving character and sweetness in much of Geert Grote‘s philosophies and on the other hand his morbid focus in his extensive writing on death and dying. A similar curious contrast also exists in his role as a fighter of heretics.

After Geert Grotes’ death in 1384, a true monastery under Augustin rule was founded at Windesheim, a place near Deventer, embracing spiritual contents based upon Geert Grote’s philosophy. This specific Brothers of Common Life monastery movement reached its apex in 1511 when about 100 satellite monasteries were functioning, all acknowledging Windesheim as their core institution of authority.

At the age of 13, Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380-1472) entered the ‘Brothers of Common Life’ school in Deventer, an institution, which included a scriptorium, their major source of revenue. The famous volume which he either wrote and/or edited , De imitatione Christi, contains four treatises (books), and was first published anonymously in 1418. Numerous reprints of De imitatione Christi followed in many languages. Reprinted during the ages in huge numbers across the world, it became the international ‘bible’ of Modern Devotion and is now said to be one of the widest distributed religious texts in the world.

De imitatione Christi is a devotion manual. It has been written in the form of short maxims (sayings, proverbs, aphorisms) to assist the reader’s mind to focus in its striving for personal holiness and communion with God. The book was primarily conceived for ascetics and monastics, in order to make them better able to adhere to the virtues of poverty and celibacy (these two basic qualities had been lacking in church circles and monastic circles).

De imitatione Christi has in the end become a widely loved and widely read text by Christians of all walks of life.

The following text by Eugène Honée in “The art of Devotion”, the catalogue to the beautiful 1994 Rijksmuseum exhibition, will give a general idea of the contents in terms of physicality and determined focus. He states:

“Thomas à Kempis also wrote many prayers, one of which is addressed to Christ’s limbs. Graphic prayers are said first to the feet, then to the legs, whence the eyes and soul are raised to the loins, the side and the Lord’s back. By way of the hands, neck, mouth, face, ears and eyes one finally ascends to the head. All parts of the body are kissed on one’s thoughts, and applied to one’s own life. At the feet, for instance, the believer asks fro forgiveness of “my misdeeds, by commission or omission”. The individual supplications close with a Hail Mary.”

Although geographically at some distance from economically and politically more important coastal towns in Flanders and Holland, the Hanseatic town of Deventer developed into a centre of learning. A Latin school was founded in there in 1483 by the humanist Alexander Hegius after returning from his travels in Italy. It was one of the first in the Netherlands. Latin schools had already cropped up in Alkmaar around 1400 , and in Gouda where an early Latin school may have existed in 1366, certainly in 1573. The one in Delft was founded afterwards and other stations are known in a number of other Dutch towns.

In Delft the Latin school was founded by a number of brethren working along the lines of the Brothers of Common Life, the movement started by Geert Grote. Typically boys in Latin schools entered at the age of 8, and the first knowledge they had to master was how to read and write.

Discussions of some representative works of art inspired by Modern devotion

In the section above on Andachtsbilder their function was defined as restricted as scenes of the life of the Virgin Mary and of the Passion of Christ, either shown separately or combined in one image.

We find early examples of these images in cloister manuscripts, and in personal prayer books, which could take the form of a Books of Hours. Mass produced images, in the form of paintings or prints also found they way into numerous private homes and into the cells of friars. Artists reinvented scenes by upgrading them to a contemporary setting, thus honing their narrative skills. One could say that not only a new technique of focusing the mind was sought in order to intensify prayer, but perhaps also triggering the emotion of being witness in a personal encounter experience. At the utmost, the faithful could even strive for mystical identification.

Panofsky (1927) shows a list of examples and discusses questions of early sources, derivation and recombination of elements from early sources such as Byzantium, Italy and Russia. Examples are illustrated by Ringbom as well (first published 1965, reprinted 1983).

Earlier on, narratives were the usual shape, showing multiple scenes of the story involved, for instance carved in ivory objects. For private prayer purposes, single, isolated elements were extracted which could stimulate prayer by bringing closeness to the one who used the image in prayer.

In order to show an overall idea of their typical qualities, some examples are discussed here.

Petrus Christus

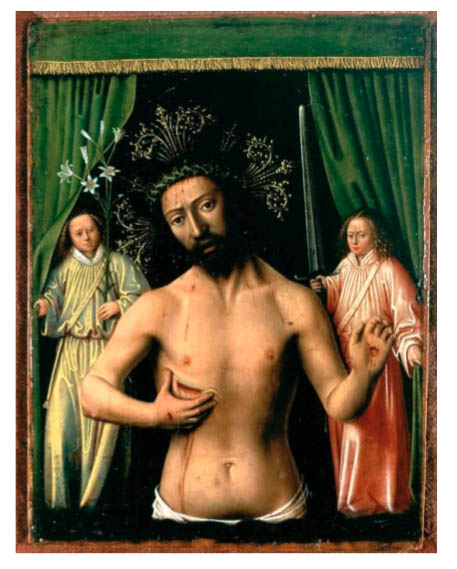

Petrus Christus

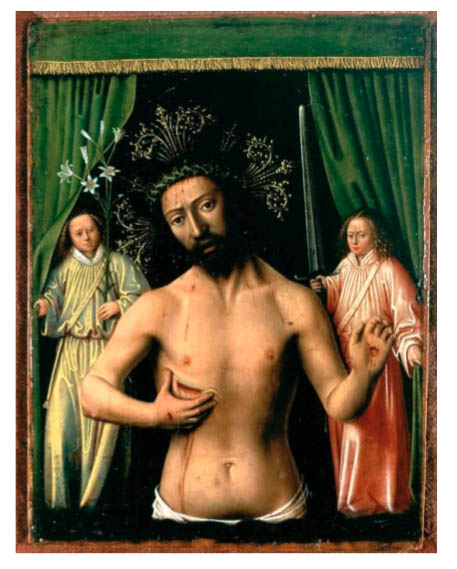

Petrus Christus, who settled in Bruges in 1444, is regarded as an important follower of Jan van Eyck, although not his direct workshop student. Petrus Christus’ works have a stylized, highly polished and finished character and also incorporate a particular, haunting quality of emotional intensity. Both of these traits are clearly present in the beautiful and arresting Andachtsbild discussed here.

Christ as the man of Sorrows by Petrus Christus (ca. 1410-1472/73) dated c. 1450, is now in the collection of The Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. It is painted on a wooden panel and thus easily portable at the size of 11,2 x 8,5 cm.

This image fuses two main sources:

a) Christ as Man of Sorrows, a half figure only wearing a white loincloth, naked from the waist up and wounded, an image known from Byzantine tradition;

b) Christ as Judge on the Day of Resurrection.

The representation of the features of His face follows the contents of a letter (purportedly) written by Publius Lentulus to the Roman Senate, in which Christ’s face was described. This letter was cited in Vita Christi by Ludolphus of Saxony (ca. 1295-1377). A similar description is contained in Meditationes Vitae Christi. In order to focus prayer, portraits of Christ were widely used. Perhaps also enticing “Gottesliebe als Selbstverlust”.

In this case, the angel standing on His right hand side (our left) is dressed in yellow and raises a lily with the left hand, whereas the other one on His left side is dressed in red and carries a raised sword of judgement with the right hand. Left-handedness and right-handedness were of crucial importance in higher social and court procedures, especially to indicate absolute and relative ranking, and this dexterity rule was also by transfer applied to the religious field.

By positioning Christ all the way forward, almost jutting out of the frame and into our earthly realm, Petrus Christus is manipulating the use of space and light within the portrait and thus assists the inner experience of the viewer, who may witness more participation, feeling closer to the Divine. If during viewing the daylight would stream in from an actual window to the left, the viewers’ space and painted light could even be attuned into one.

Petrus Christus succeeds in heightening the experience of identification of the user with the Divine by various visual means:

The background of the painting consists of a theatre-like framing, with a bright green valance on top and curtains made of the same light green fabric to the right and left side. These curtains are held wide open by the two angels without wings who are both looking at Christ, their heads tilted in different ways, dressed down to their feet in luxurious changeant fabrics.

The overall effect is that of imitating a theatrical setup or even that of a protective cover of fabric used in real life to shield actual paintings from dust and light. If the latter case is valid, one may even consider this image as an early form of trompe l’oeil.

In front of the angels stands the looming figure of Christ, who is taking centre stage both in position and relative size. The light streams into the interior room from his right side (our left hand side). With his right hand he indicates and even physically stretches and widens the wound in his chest, inflicted during crucifixion by the Roman soldier who was in later texts indicated as Longinus. This soldier was attempting to ascertain whether Christ was alive on the cross. Christ’s left hand is raised, the fingers lightly curled. From His head, still carrying the bloodstained crown of thorns, emanates an otherwise seldom seen setup of curved rays fanning out, one on top and one on each of the two sides, resembling the shape of an oversize tiara or crown, and also echoing the cross shape. The function of this ornament is perhaps to show an exalted meta reality, an abundant blossoming radiation of His divine spiritual energies.

The owner of this panel may have used this tiny panel in a private study, as a means of focusing attention during private prayer and meditation. No pertinent information is known in literature on the initial patron who ordered it and the other early owners and users.

The gaze of Christ is not immediately directed at the viewer but is veering off a bit, looking somewhat vacant to the lower left hand side of the viewer (thus to the right of Christ), as if to avoid too much direct contact. The body of Christ is shown as only lightly bloodied from the crucifixion in the hands, the head with the crown of thorns and the chest, with the spear wound. Compared to the Germanic tradition of painting extremely gruesome and bloodied bodies of Christ, this image is fashioned in a reticent way.

One may also look at this painting in terms of a visionary image. Visionaries stand at a threshold of distinct worlds and communicate between the inside and the outside, according to Hildegard Elizabeth Keller.

Next we will study the effects of a picture, which combines the portraits of Christ and Mary.

Robert Campin

Robert Campin

Robert Campin, also known as the Master of Flémalle (ca. 1378-1444) was active in Tournai (Doornik) from 1405-1406. The painter’s fame has disappeared for ages, unknown for many centuries for lack of signed paintings. His oeuvre was subsequently recognized and analyzed by art historians, based on stylistic arguments.

The Andachtsbild discussed here is Christ and the Virgin from c. 1430-35. This painting in oil, with an abstract background of gold on panel, is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Its present size is 28,6 x 45,6 cm, but upon delivery it once stood taller as the top was cut down.

It is a historicized double portrait. We see Christ who is facing us straight on, His eyes again veering off to a point at our right (His left). To His left is a three-quarter portrait of His mother Mary, her head turning towards Him. As no true historical portrait has come down the ages of either figure, painters have chosen to follow age-old tradition, starting in the Early Christian and Byzantine era.

His rosy coloured skin is offset here with a somewhat scruffy beard and His long dark hair. He is dressed in red, with a precious stone hanging on a gold necklace in the middle on His chest. His right hand is positioned in a blessing sign, two fingers raised and His other fingers are resting on a high ledge, which is part of the painted image. Oddly His body position seems ill-fitting within the frame, hardly tall enough to reach up to that ledge level. The oddity is increased in His face by the fact that His eyes are not positioned in a regular correct position midway between chin and the top of the skull. Moreover the eyes seem to be set too much towards each other. This combination of deformities may or may not be intentional or may or may not be devised to enhance expressive value.

Mary is positioned to the right, thus to His left hand side, and is also dressed in red, but with a billowing loose blue headscarf, and blond well-kempt hair and she has a fair skinned, almost a pale complexion. She is intently looking towards Christ, immersed in devotion, her hands raised together in a prayer position, fingers pointed upwards. Many Christians felt naturally close to Mary, and had little hesitation seeking her help in prayer.

The background of the panel is covered in gold with a partly raised surface of precious stones arranged in a fanning-out cross-shape and circles.

Combining the heads of the adult Christ with that of Mary was something of an innovation. Earlier tradition included the two figures presented entirely separate, or showing Jesus as a baby or toddler on Mary’s lap, or Christ as corpse stretched out across Mary’s lap, in a harrowing Pietà.

What makes this painting impressive for the modern day viewer and certainly for the late mediaeval user is its rather large size. The user could filling the entire visual space when it was set up in front, on a table, during private prayer. The gold background and tonal qualities helped to elevate the scene from earthly to heavenly spheres. The wooden ledge painted at the bottom forms a trait d’union: it ties the world of the onlooker and the two figures into one. It is as if the viewer could also wish to seek to extend a hand to that same ledge and enter into tactile contact, a hesitant physical union across space, time and universe.

Christianity generally advocated closeness of the believers to bodily remains of deceased saints, and commended travel to their burial places in a pilgrimage. It was understood that physical remains of holy persons radiated holiness and could help the faithful on the path to salvation. The bodily remains of a Saint were sanctified and thus already fully freed of the desires of the flesh. By renouncing the ways of the flesh and the ways of the world, Christians strove for purity in their pathway to God. For the human body was a vessel of sin and corruption.

It should however also be noted that by contrast some mystical visionaries went against that very grain, and penetrated into the realm of corporeal intimacy. An uncontested scene in Christian art shows the baby Christ suckling Mary’s breast (Panaghia Galaktotrofoussa, or the Virgin Lactans), but some mystics like Bernard of Clairvaux went steps further in seeking closer communion and described their visions such as drinking the Virgin breast milk in the rapture of prayer. This topos underlines the exceptional corporeal nature of some medieval religious visions, so unrestrained, and so exhilarating that they still amaze us today.

Mary was the human vessel flesh in which the supreme Deity chose to implant the earthly existence of Christ, and therefore her body was regarded as ultimately pure, unblemished by original sin.

Antonello da Messina

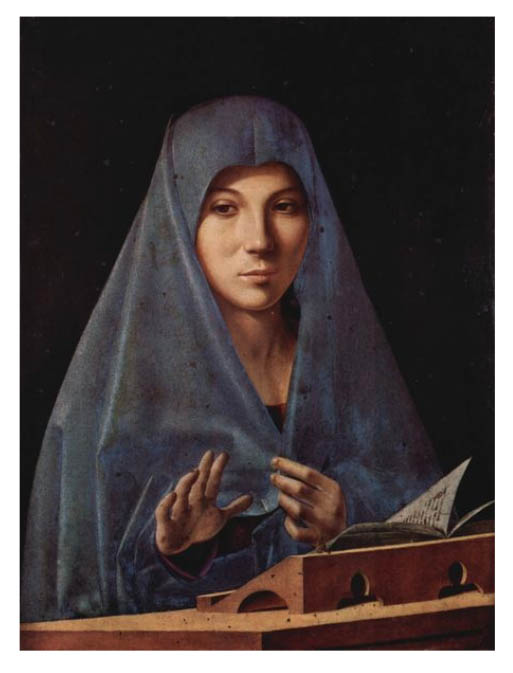

Antonello da Messina

Antonello da Messina (1444-1493) is the Italian Renaissance artist most deeply influenced by Flemish painting. His initial training was in Sicily and during his travels, which brought him to Naples, he was struck seeing a painting by Jan van Eyck in the collection of King Alphonso of Aragon. Subsequently he travelled to Bruges in order to study the outstanding painting technique there. He finally returned to Italy in 1465, first to his hometown of Messina and seven years later to Venice.

Antonello da Messina painted at least two versions of the Virgin Annunciate or l’Annunziata indicating the story of the angel of the annunciation suddenly interrupting Mary. The latter one shown here, currently in Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, dating from c. 1476, is the most famous one because of the compression of space and devices as the successfully foreshortened outstretched hand. An earlier version, dated 1473, with her hands crossed in a protective position across the heart, is in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

In both pictures, the person at prayer in front of this image, perhaps using a book of prayer, may feel an additional connection with Mary, who is using a book as well.

In this Palermo picture, in oil on wood, 45 x 34,5 cm., the viewer is caught in the middle between two entities: the Virgin who is suddenly observing the angel, and the Archangel Gabriel who has just entered her room.

The author Robert A. Gahl, jr states that four time frames in the story given by the gospel author Luke in Luke 1, 26-38, have been successfully compressed into this one image of almost cinematographic quality:

Accepting this particular and intricate reading of the four frames compressed into this one work, the incarnation of Christ, an event of cosmic importance to Christians, is represented here in a truly extraordinary way. If aware of the unfolding of the four steps in time of the story, the viewer may also be aware of being positioned in a central line between Mary and the Angel, thus becoming a witness to the incarnation, the Divine will in progress. Taking away the angel from the annunciation image is an early example of “Herauslösung”, a technique much used later on by Rembrandt to simplify and intensify the storytelling in his history paintings.

Antonello da Messina has successfully incorporated the Flemish obsessions in stark realism. Thus in the strong physicality of the body is Flemish in nature, but he has intellectually raised the contents of the image by compressing the four time frames. The total image nevertheless remains visually coherent.

We have no information whether the artist sought or received advice as to the particular contents, for instance by a knowledgeable church official. Generally, evidence exists of such advice in contracts between artist and patron that an advisory role was a regular practice.

Conclusion

Conclusion

In this chapter I have first sketched the nature of the Andachtsbild.

From the selected examples it is clear that these artists, in producing devotional paintings, were keenly aware of the function, particularly on the mental effects of the user. In prayer, the Andachtsbild was employed to intensify communication on a spiritual level.

Physically it was just a simple panel, treasured and well protected, wrapped up in fine cloth or leather, stored in a proper dry place, to be opened at will by the user. In case it was a hinged, foldable object (diptych, triptych, polyptych), the moment of opening up in the privacy of the study room would perhaps become a recurring cherished ritual.

The Andachtsbild helped to channel and focus attention and may have established a heightened experience of close prayer contact between the faithful person and the Divine or Saintly power. This prayer-viewer-image relationship was gradually fine-tuned as generations of artists progressed in knowledge of prayer practice, knowledge of the human psyche and knowledge on how to finely craft these objects. Patrons progressed as well, and became more focused / intelligent especially those laypersons well educated in the fine arts and in the art of private, personal prayer.

Copyright Kees Kaldenbach, Amsterdam

kalden@xs4all.nl

www.johannesvermeer.info

Last edited July 15, 2011.

Unpublished manuscript. Put online June 15, 2012.

===

Literature. A book discovered later on: Moderne Devotie. terug naar de bron met Geert Groote en Thomas a Kempis. De Moderne Devotie in Deventer en Zwolle. Pubisher: W books + Stedelijk Museum Zwolle, Historisch centrum Overijssel, 2011.

====

Eugène Honée, ‘Image and Imagination in the medieval culture of prayer: a historical perspective’ in: Henk van Os, 1994, p. 157.

http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/definition/veneration seen January 19, 2008.

Opinions vary as to the authorship; was it Thomas a Kempis by himself or Thomas a Kempis reworking earlier writings by Geert Grote?

http://cf.hum.uva.nl/bookmaster/librije/nota/mark.htm viewed January 15, 2008.

http://www.bmagic.org.uk/objects/1935P306 online January 15, 2008.

Hugo van der Velden, ‘Diptych Altarpieces and the Principle of Dextrality’, in: Essays in Context. Unfolding the Netherlandish Diptych, 2006, pp. 124-155.

The winged figure (of a genius) was a tradition in Roman sculpture and was seen on countless sarcophagi and also in other sculptured items from antiquity. See also Van Os, 1994, p. 18.

Pseudepigraphical sources: See the appendix to the Acts of Pilate and see theGospel of Nicodemus, 8:4.

Hildegard Elizabeth Keller, ‚Absonderungen. Mystische Texte als literarische Inszenierung von Geheimnis’ in: Deutsche Mystik, 2000, p. 206: “Damit komme ich zu den Schwellenhütern im primären Sinn. Die Visionärinnen und Visionäre selbst stehen auf der Schwelle und vermitteln zwischen Innen und Außen.“

Perhaps the pre-Christian traditions of seeking contact with the female deity Mother Earth was hidden underneath that human experience of easy access.

http://www.edscuola.it/archivio/interlinea/annunziata.htm, text written April 28, 2003, downloaded January 17, 2008,

Adriaen Coorte, by Quentin Buvelot, book & exhibition catalogue.

De Grote Rembrandt, door Gary Schwartz, boek.

Geschiedenis van Alkmaar, boek.

Carel Fabritius, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

Frans van Mieris, Tentoonstellingscatalogus.

From Rembrandt to Vermeer, Grove Art catalogue, book.

Vermeer Studies, Congresbundel.

C. Willemijn Fock: Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld, boek.

Het Huwelijksgeschenk (1934), boek over de egoïstische vrouw, die haar luiheid botviert.

Zandvliet, 250 De Rijksten van de Gouden Eeuw , boek + nieuwe stippenplattegrond!

Ik doe wat ik doe, teksten van Lennaert Nijgh , boek + cd

Het Rotterdam Boek, boek.

Bouwen in Nederland 600 - 2000, boek.

Hollandse Stadsgezichten/ Dutch Cityscape, exhib. cat.

Zee van Land / over Hollandse Polders (NL) boek

Sea of Land / about Dutch Polders (English) book

A full article on the large portrait of the marvellous preacher Uytenboogaard.

Artikel over Uytenboogaerd, Nederlandse versie.

Geert Grote en het religieuze Andachtsbild

TEFAF 2008 art fair

About Art Historian Drs. Kees Kaldenbach: Read a biography.

How to find Drs Kaldenbach:

Map of Haarlemmermeerstraat, Amsterdam. Please note this tricky situation: there is another street in town that sounds almost the same: Haarlemmerstraat. You need however to find my street, Haarlemmermeerstraat. Take tram 2 to Hoofddorpplein square or tram 1 to Suriname plein square.

Contact information:

Drs. Kees Kaldenbach , kalden@xs4all.nl

Haarlemmermeerstraat 83 hs

1058 JS Amsterdam

The Netherlands

telephone 020 - 669 8119

(from abroad NL +20 - 669 8119)

cell phone 06 - 2868 9775

(from abroad NL +6 - 2868 9775)

How to get there (after your booking confirmation!):

- by car: ring road exit S 106 towards the centre, then 1st to the right (paid parking)

- by trams 1 and 17; exit at Surinameplein

- by tram 2; exit Hoofddorpplein.

From the museum square it takes about a 10-minute tram ride.

Read client testimonials. Read a biography.

Photo by Dick Martin.

Reaction, questions? Read client testimonials.

Drs. Kees Kaldenbach, art historian, kalden@xs4all.nl Haarlemmermeerstraat 83hs, 1058 JS Amsterdam (near Surinameplein, ring road exit s106, streetcar tram 1 and 17).

Telephone 020 669 8119; cell phone 06 - 2868 9775.

Open seven days a week.

Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce (Kamer van Koophandel) number of Johannesvermeer.info / Lichaam & Ziel [ Body & Soul] is 3419 6612.

E mail esponses and bookings to art historian Drs. Kees Kaldenbach.

This page forms part of the 2000+ item Vermeer web site at www.xs4all.nl/~kalden

Launched 17 june 2012. Updated 27 October 2016.

Column 2006 - 1 Farmacie & het imago-probleem

Column 2006 - 2 Echt ziek zijn en alternatief beter worden

Column 2006 - 3 Blues in de dokterskamer, met een Marokkaans kind als tolk-vertaler

Column 2006 - 4 Innovatie als tweezijdige vikingbijl

Column 2007 - 1 Patient versus client van de troon en de vuist

Column 2007 - 2 De hellevaart van de Brent Spar

Column 2007 - 3 Perspectief: laat anderen eens goed naar je kijken

Column 2007 - 4 Hermes, Alchemie en de Quintessence

Column 2008 - 1 Lees het dan! Het staat hier toch duidelijk!

Column 2008 - 2 Transparante retorica. Een democratisch goed