Tables

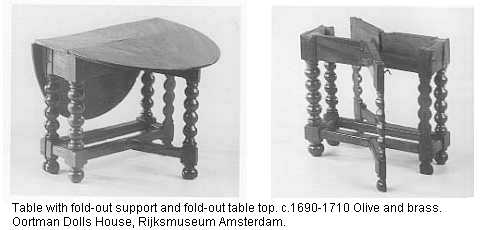

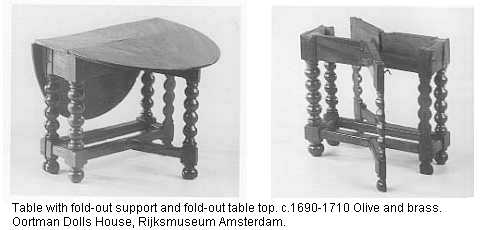

with a pull-out table top, 'uittrekkende tafel', found in the

Great Hall and in the upstairs front studio.

Tables

with a pull-out table top, 'uittrekkende tafel', found in the

Great Hall and in the upstairs front studio.

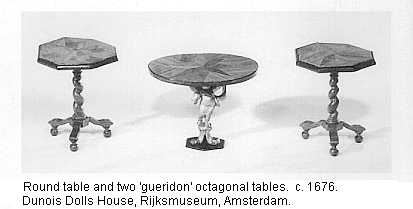

Table, 'tafel', found in the inner kitchen. In Vermeer paintings we often see thick tablecloths not lying flat but draped. See also trestle table.

Table manners. In his 1733 book author Jacob Graal gives extensive advice on how to behave at the dinner table, especially how one should cut meats.

At the table one waits standing up until one is seated; and when sitting one sits straight up and never puts the elbows on the table. One does not attack the food and wolf it down: "One should not be the first to take food off the dish by hand..." (p. 74) for the first pick is the prerogative of the elevated (p. 98). And one may not be picky: "one should accept everything with grace..." (p. 98).

Licking of fingers, knife or spoon is forbidden: "there is nothing more gross..' (p. 102); one should use the napkin in stead. Picking teeth is not done. (p. 108).

A glass of wine is not to be gulped in one but should be had in two or three times (p. 106).

Do not use uncouth language, wild or crazy talk (p. 108).

Do not propose to sing at the table oneself ; wait until one is invited repeatedly to do so and keep it short. (p. 116).

All this fits in wonderfully in the concept of the ongoing Civilisation Process (book by Norbert Elias); but a shocking dissection of an entire calf's head at the dinner table is accepted (page 90).

Household functions. Not all functions of daily life had been allocated their own specific space in the seventeenth century house. Rooms were used simultaneously for a variety of functions. One could eat and sleep in the kitchen and in the Great Hall, and when one comes across beds in inventories of a particular room this does not say much about daily use or specific use. Dining tables could be placed anywhere (Pijzel, Pronkpoppenhuis, 2000, p. 401, note 151). A pull-out table is also mentioned in Fock 2001, p. 24.

Note

: This object was part of the Vermeer-inventory as listed by the

clerk working for Delft notary public J. van Veen. He made this list

on February 29, 1676, in the Thins/Vermeer home located on Oude

Langendijk on the corner of Molenpoort. The painter Johannes Vermeer

had died there at the end of December 1675. His widow Catherina and

their eleven children still lived there with her mother Maria

Thins.

Note

: This object was part of the Vermeer-inventory as listed by the

clerk working for Delft notary public J. van Veen. He made this list

on February 29, 1676, in the Thins/Vermeer home located on Oude

Langendijk on the corner of Molenpoort. The painter Johannes Vermeer

had died there at the end of December 1675. His widow Catherina and

their eleven children still lived there with her mother Maria

Thins.

The transcription of the 1676 inventory, now in the Delft archives, is based upon its first full publication by A.J.J.M. van Peer, "Drie collecties..." in Oud Holland 1957, pp. 98-103. My additions and explanations are added within square brackets [__]. Dutch terms have been checked against the world's largest language dictionary, the Dictionary of the Dutch Language (Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal , or WNT), which was begun by De Vries en Te Winkel in 1882. In 2001 many textile terms have been kindly explained by art historian Marieke te Winkel.C. Willemijn Fock, Titus M. Eliëns, Eloy F. Koldeweij, Jet Pijzel Dommisse, Het Nederlandse interieur in beeld 1600 - 1900 Waanders, Zwolle 2001.

Illustration taken from the recently published handbook on Dutch Doll Houses by Jet Pijzel-Dommisse,Het Hollandse pronkpoppenhuis, Interieur en huishouden in de 17de en 18de eeuw, Waanders, Zwolle; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2000, ill.135, 552.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 2, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.s