To

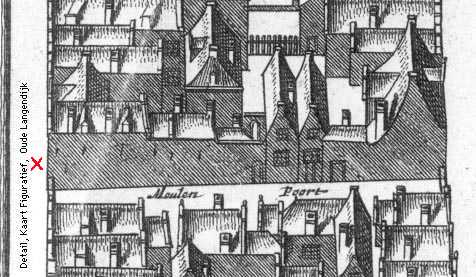

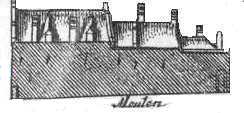

the left a detail of the Kaart Figuratief Map

(1675-78)

To

the left a detail of the Kaart Figuratief Map

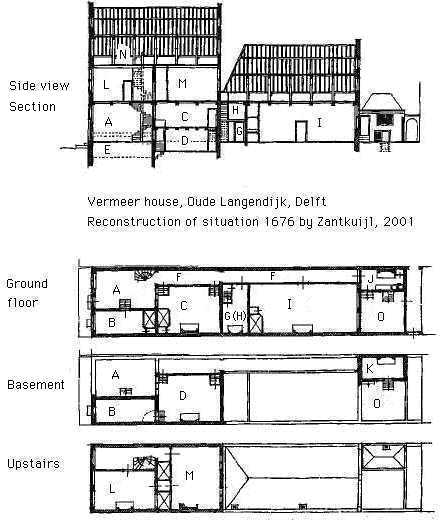

(1675-78)Expanation by restoration architect dr. ing. Henk J. Zantkuijl* of his drawings of the Vermeer house floor plans and elevations.

Read about the controversy voiced by Professor Philip Steadman on the difference between Zantkuijl drawings and Warffemius drawings.

A critique by Glaudemans

To

the left a detail of the Kaart Figuratief Map

(1675-78)

To

the left a detail of the Kaart Figuratief Map

(1675-78)

there are four points of departure for this reconstruction. These

are:

a. The Cadastral map of 1832 (see below).

b. The Figurative (Kaart Figuratief) map of 1675-78 (see

below).

c. The 1676 inventory (see the full presentation of this inventory

with many images).

d. Archival research yielding knowledge about the development of the

house.

In this examination we will also see whether the interiors shown in Vermeer paintings can be fitted within this reconstruction. If this is possible within bounds of reason we will note whether the details of the interior views on paintings add anything to this reconstruction.

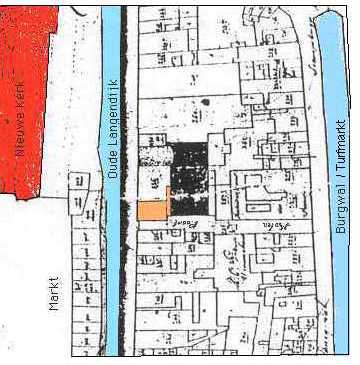

The

Cadastral Minute map of 1832 (detail to the left) shows a corner

house standing on Oude Langendijk and Molenpoort, having a length of

about 12 meters, with an alleyway stretching behind the neighbouring

house. This has been coloured orange.

Behind this is a cleared garden area belonging to another neighbor

(it was coloured black on the original 1832 map).

The

Cadastral Minute map of 1832 (detail to the left) shows a corner

house standing on Oude Langendijk and Molenpoort, having a length of

about 12 meters, with an alleyway stretching behind the neighbouring

house. This has been coloured orange.

Behind this is a cleared garden area belonging to another neighbor

(it was coloured black on the original 1832 map).

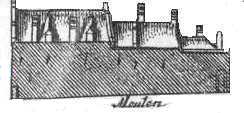

On the other hand the Figurative Map (1678, see below for a detail of this map) shows a long house which consists of a high part at the corner, a lower part towards the middle and finally a small shed towards the east side, and a small yard and a pathway which lead to the hidden church run by the Jesuits in one of the neighboring houses.

On the Cadastral Minute map of 1832 this pathway is still visible behind the blackened garden. The total length of this house is now clear to us. It measures 32 meters including shed, yard and pathway. The corner house measuring some 12 meters is practically the same size as the high section shown on the Figurative Map (1678).

Between 1676 and 1733 the middle and back part of this house were demolished.

The rooms mentioned in the 1676 inventory can be easily fitted into this building with its three parts ranging from high to low. The drawings which are published below contain the letters signifying the rooms mentioned in the 1676 inventory..

|

NEDERLANDS - DUTCH, 1676 |

ENGLISH EQUIVALENT |

FLOOR PLAN, 2001 |

|

Int Voorhuys |

Forehouse |

Zantkuijl A |

|

Inde groote zael |

Great hall |

Zantkuijl I |

|

Int Camertie aende voorz. groote zaal |

Small room adjoining the Great Hall |

Zantkuijl G |

|

Inde binnenkeucken |

Inner kitchen |

Zantkuijl C |

|

Int agter keukentgen |

Back kitchen |

Zantkuijl J |

|

Inde koockeucken |

Cooking kitchen |

Zantkuijl D |

|

Int waskeukentgen |

Washing kitchen |

Zantkuijl K |

|

Inde gang |

In the hallway |

Zantkuijl F |

|

Op de keldercamer |

Room above the cellar |

Zantkuijl B |

|

Op de plaets |

In the yard |

Zantkuijl O |

|

Opt hangkamertgen |

In the small hanging room |

Zantkuijl H |

|

Boven op de agtercamer |

Upstairs back room |

Zantkuijl M |

|

Opde voorkamer |

Upstairs front room (VERMEER STUDIO) |

Zantkuijl L |

|

Boven op de solder |

In the attic |

Zantkuijl N |

|

[Niet op lijst: Kelder] |

[Not listed: Cellar] |

Zantkuijl E |

|

[Niet op de lijst: Wenteltrap] |

[Not listed: Spiral staircase] |

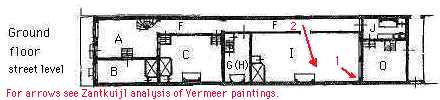

A. forehouse

B. room above cellar

C. inner kitchen

D. cooking kitchen

E. cellar

F. hallway

G. small room adjoining the great hall

H. little hanging room

I. great hall

J. back kitchen

K. washing kitchen

L. upstairs front room (studio)

M. upstairs back room

N. attic

O. the yard

The Figurative Map shows a side wall without windows with an entrance gate. The windows of the houses next to it have however been fully drawn. This is why we have chosen - in our initial floor plan - to show a side wall without windows, in which cramp irons (wall-ties) have been fitted. Nothing is known to us of the architecture proper. In constructing this construction we have used our knowledge of similar houses, given the era and the form.

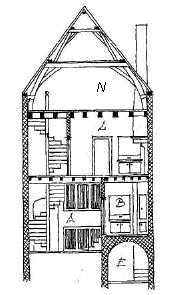

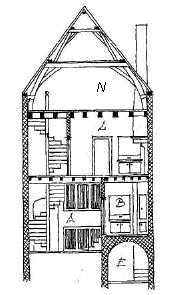

The beam construction shown in this section drawing has been defined in order to separate the rooms from each other and to give an idea of the possible dominating influence of the beams on these rooms. The construction shows us that this house was possibly built in two phases. The corner house is a well known town house, consisting of a forehouse (in this case with a basement), a hallway and an inner hearth with split level. The lower part of this split level contained the kitchen (mentioned in the inventory als cooking kitchen) with above it the high room in which the family lived (the inner kitchen in the inventory). On the upstairs floor there were a front room and a back room. To this type of house one could add a Great Hall later on.

N. attic

L. upstairs studio

A. forehouse with interior windows lighting the inner kitchen and the

cooking kitchen.

B. room above the cellar

E. cellar

Twenty

five paintings by Vermeer show interiors which may be used for our

purpouse. The characteristic details especially of the

cross-bar frame show that these

paintings have been made after examples from real life. Now the

central question is whether these details can be entered within this

reconstruction. This becomes the more interesting as the construction

stems from the above mentioned four points of departure, independent

of the painted interiors. However, the interiors provide so many

architectural details that an attemt shall be made here to fit the

interiors within our reconstruction. In choosing the paintings we

will mention the page showing the picture in the exhibition catalogue

Johannes Vermeer in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

and the Mauritshuis, The Hague / 1995-1996.

Twenty

five paintings by Vermeer show interiors which may be used for our

purpouse. The characteristic details especially of the

cross-bar frame show that these

paintings have been made after examples from real life. Now the

central question is whether these details can be entered within this

reconstruction. This becomes the more interesting as the construction

stems from the above mentioned four points of departure, independent

of the painted interiors. However, the interiors provide so many

architectural details that an attemt shall be made here to fit the

interiors within our reconstruction. In choosing the paintings we

will mention the page showing the picture in the exhibition catalogue

Johannes Vermeer in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

and the Mauritshuis, The Hague / 1995-1996.

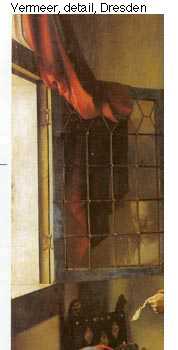

A detail which may be important for dating this house is the cross-bar frame with an added window (in Dutch: voorzetraam), which has been depicted in the following Vermeer paintings:

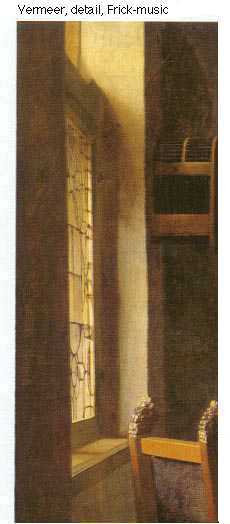

Interrupted Music 1660-61, Frick, page 24.

The Lute Player c.1664, Metrop., page 26.

The Music Lesson 1662-64, Buckingham, pag.129.

Woman with Pearls c.1664, Berlin, page 153.

Writing Woman with Maid c.1670, Dublin, page 187.

Standing Virginal Player ca.1672-73, NG London, page 197.

Seating Virginal Player before 1670, NG London, page 201.

Two varieties of the cross-bar frame can be distinguished, being four cross-bar windows with a beveled side in the upper section by the leaded glass (page 26, 129, 153 en 187) and one with a straight profile (pag.197). On pages 24 and 201 the shape of the upper part is not visible.

We can learn more from the added interior window. Its historical development went like this:

The stone cross-bar frame can be seen as the oldest type of window frame. Afterwards the wooden cross-bar frame followed. Both types had four sections. Normally the light entered through two leaded glass window which were both attached to the upper two sections of the cross bar frame. In the lower part the shutters closed off the lower two sections. They were either hinged on the inside, turning in, or hinged at the outside, turning out.

The shutter in the lower section was eventually found mostly on the outside. If one stood inside the house and wanted to look outside, one had to open one of the shutters - which was not convenient during rain or chilly weather. In order to solve this problem two added interior windows were attached on the inside, in which panes with leaded glass were attached. This transition period is hard to date as early wooden cross-bar windows are scarcely known.

However, a documented example is the description of a Master Carpenter's trial proof for house carpenters in Amsterdam dating 1524. In this job a beam with given measures had to be tooled into a cross-bar frame with double grooves or rabbets (Dutch: 'dubbele sponden'). It is understood that this entailed a cross-bar frame with added interior windows. The fact that this was extraordinary can be seen in a builders' specification from the middle of the 16th century in which frames for leaded glass are required.

In the late 16th century and he entire 17th century a lower interior window has become the norm.

A

clear documentary example of this type of cross-bar frame with lower

interior window is depicted by Vermeer in the painting 'Girl Reading

a Letter' Dresden (page 73). It should be noted that this frame has

been placed in a wall which has the thickness of the cross-bar frame

, thus circa 20 cm., with a nude measure [being the beveled edge

in which the window could be closed] of about 25 cm. This shows

that this frame has been placed in a wall or sidewall or in a fairly

thin seventeenth century facade gable.

A

clear documentary example of this type of cross-bar frame with lower

interior window is depicted by Vermeer in the painting 'Girl Reading

a Letter' Dresden (page 73). It should be noted that this frame has

been placed in a wall which has the thickness of the cross-bar frame

, thus circa 20 cm., with a nude measure [being the beveled edge

in which the window could be closed] of about 25 cm. This shows

that this frame has been placed in a wall or sidewall or in a fairly

thin seventeenth century facade gable.

The cross-bar frame with added interior window mentioned above is quite special within the development of the cross-bar frame. It was not easy to consruct an interior small lower window frame, hacking these into an existing large frame.

In order to solve this problem such as shown in Vermeer paitings, the carpenter constructed a framed wall [Dutch: 'stijl en regelwerk'] at the inside of the two lower rectangles, allowing the window to hinge.

Here we are dealing with an old large window frame, presumably from the sixteenth century.

Another remarkable fact is that these cross-bar frames have been placed in a thick facade wall. This can be precisely observed as the remaining inside portion of the wall [in Dutch 'dagkanten'] on Vermeer paintings certainly is no less than 20 to 25 cm. This remaining part of the wall can be best seen in 'The Musical Lesson' (pag.129). The window frame is part of the street facade side of the house and is some 20 cm. thick, which yields a total wall thickness of 40 to 45 cm. This points at a massive facade constructed of natural stone or bricks, which in itself points at the 16th century. The question where exactly this cross-bar frame with added interior window was placed the connection with the side wall is of importance. The side wall is and the side of the window frame are flush ; there is no wall pier [in Dutch: 'muurdam'].

The side wall of the house (as we are looking at it being the back wall) normally has a thickness of one brick, varing from 20 to 25 cm. The width of the entire Vermeer/Thins house facade is known to us (from the Kadastrale minuut Map) as being 6.70 m. With this width there will have been three window bays holding three cross-bar frames. The size of one cross-bar frame was fixed at 1,56 m. which yields wall piers of circa 50 cm. If and when this wall were a side wall - then a wall pier of at least 25 cm. should be visible - see the connection between side wall and facade gable in the 'Girl reading letter' page 73. This is not the case. Therefore the wall next to the cross-bar frame with added interior window is not a side wall but an inner division wall which structurally yields to the construction of the wall frame in the facade. In the Vermeer/Thins house his situation can be found upstairs at the front, in Vermeer's workshop, see room L. Another way of locating the space within the Vermeer/Thins house is observing the height of the 'parapet' which is the wall between the lowest section of the window frame and the floor. In the seventeenth century and before the height of his parapet on the ground floor is at least 1 meter and usually 1,20 meters. On the upstairs floor which offers no chance of looking in from the street and in which the ceiling height is lower, we find parapets of 90 cm. or even lower. All of the cross-bar frames with added interior window have a low parapet, which allows for a placement upstairs in the front of the Vermeer/Thins house. There are several other paintings with low parapets, which are:

Drinking

Lady and Gentleman, 1660, Berlin, page 36

Drinking

Lady and Gentleman, 1660, Berlin, page 36

The Art of Painting 1666-67, Vienna, page 68 (the height of the

parapet canntot be seen here but the flow of light shows a low

parapet)

Lady with two Gentlemen, 1659-60, Braunschweig, pag.115

Woman with Water Pitcher 1664-65, Metropolitan, New York City page

146. In this latter painting and in the 'Drinking Lady' (page 36) we

canot discern an added interior window but we do see an interior

dividing wall, which is comparable to that window with a added

interior window .

The painting 'Interruption of Music' (page 24), showing a low parapet does have a wall dam pier in the corner, which indicates a space somewhere on the upstairs floor.

The thick wall in which the window frame is placed could be the back gable of the main house; this allows us to pinpoint the place in the Vermeer/Thins house as the right hand corner of the back room.

A remarkable point in these paintings which I place in the upstairs front room, which is the Atelier or Studio, is the leaded glass in the window rames which turn inward. There are two types, one without and one with coloured glass, both having the same general shape.

Vermeer paintings without coloured glass are:

Interruption of Music, Frick, (page 24)

The Lute Player, Metropolitan, (page 26)

The Music Lesson, Buckingham Palace, (page 129)

Woman with Water Pitcher, Metropolitan, (page 147)

Woman with Pearl String, Berlin, (page 153)

Vermeer paintings with coloured glass are:

Drinking Lady and Gentleman, Berlin, (page 36)

Lady with Two Gentlemen, Braunschweig, (page 115)

Writing Lady with Maid, Dublin, (page 187)

There is one painting whose scene could be placed in the studio for the details mentioned above, but it is lacking leaded glass in the added interior window , the 'Standing Virginal Player , NG London (page 197). This window is remarkable as the upper parts of the cross-bar frame do have a more refined profile. Has this been a painterly liberty?

There is another detail requiring attention. In two paintings a beamed ceiling has been depicted, in 'The Art of Painting', Vienna (page 68) and the 'Music Lesson', Buckingham Palace (page 129). In my reconstruction drawing of the ground floor I presented a beam structure with crossbeams and joists. This was done because of the supposed building period (in the 16th or 17th centuries) and the wall anckors which can be seen in the Kaart Figuratief. This beam system covers the width of this house from structural side wall to structural side wall, which is the most logical construction indeed. On the upstairs floor another type of beam system has been drawn, going back from the street facade to the dividing wall and again from this dividing wall to the back gable. The span is equal to that of the ground floor, circa 6 meters.

It

may seem that we do present this beam system here because of

the Vermeer paintings. However, we chose this type of beam

construction based on the series of rational points of departure

mentioned before, and this is firmly based on the present-day body of

knowledge about the way houses were constructed. A 90-degree rotation

in the direction of beams was often applied in the 16th century. This

is caused by the heavy facades which could bear the load of beams.

This allows the pressure on the foundation to be equally divided

between facade, side walls and back gable. In the 17th century the

facades became thinner and the foundation of walls was improved. Two

types of beam systems were frequent in the 16th century and the first

half of the 17th century, employing the best decorated beams above

the ground floor, such as the crossbeams and joists in this case.

It

may seem that we do present this beam system here because of

the Vermeer paintings. However, we chose this type of beam

construction based on the series of rational points of departure

mentioned before, and this is firmly based on the present-day body of

knowledge about the way houses were constructed. A 90-degree rotation

in the direction of beams was often applied in the 16th century. This

is caused by the heavy facades which could bear the load of beams.

This allows the pressure on the foundation to be equally divided

between facade, side walls and back gable. In the 17th century the

facades became thinner and the foundation of walls was improved. Two

types of beam systems were frequent in the 16th century and the first

half of the 17th century, employing the best decorated beams above

the ground floor, such as the crossbeams and joists in this case.

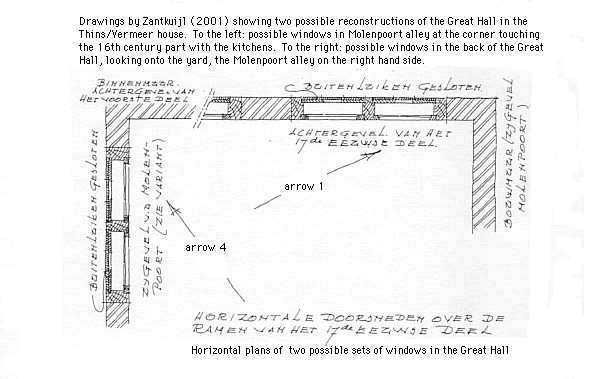

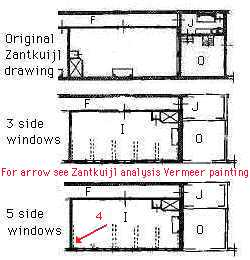

As indicated above we heve chosen a blind wall in the Molenpoort alley. The light entering the Great Hall came from two cross-bar frames in the back alley. Thus the chimney has been positioned in the middle of the Great Hall, against the side wall.

If we go for an alternative view - and suppose a series of windows in the side wall, then a construction drawing with a series of windows might be possible, as indicated in figure 6. I have drawn two alternative setups, one with three and one with five windows. Because of the ceiling structure a setup with five windows is preferable. In that situation the chimney must be placed in the back gable against the yard. It should be noted that a chimney has been drawn just there on the Figurative Map (Kaart Figuratief).

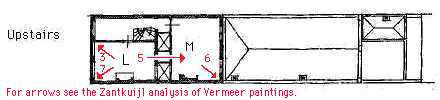

In summary we may place Vermeers interoir paintings as series of arrows within our reconstruction.

Arrow-1, Great Hall, corner

of back gable and side wall

'Soldier and laughing Girl', Frick, page 35

'Girl Reading Letter', Dresden, page 73

'Astronomer', Louvre, page 52

'Geographer', Frankfurt, page 171

For arrow 1 see also a the variant possibillity within the Great

Hall.

Arrow-2, through the door

in the hallway, seeing into the Great Hall with a part of the

chimney

'Love Letter', Rijksmuseum, page 181

Arrow-3, upstairs floor, studio, corner of facade and either side wall or interior division wall.

'Lute Player', Frick, page 26

'Drinkig Lady', Berlin, page 36

'Art of Painting', Vienna, page 68

'Music Lesson', Buckingham Palace, page 129

'Woman with Scales', Washington, page 141

'Woman with Water Pitcher', Metropolitan, page 147

'Woman with Pearl Necklace', Berlin, page 153

'Writing Woman with Maid', Dublin, page 187

'Allegory of Faith', Metropolitan, page 191

'Standing Virginal Player', NG London, page 197

'Sitting Virginal Player', NG London, page 201

Arrow-5, first floor, hallway between front room and back room.

'Girl Asleep', Metropolitan, page 20

Arrow-6, first floor, back room, corner of back gable and side wall.

'Interruption of Music', Frick, page 24

Arrow-7, first floor, front room, Studio, curner of facade and side wall.

'Guitar Player', Iveagh-London, page 32

To the left: the Great Hall, my initial drawing on top and two variant drawings below. Arrow-4, In this variant of the Great Hall, showing five windows, all paintings mentioned under Arrow-1 could be placed.

Entirely

separate from Vermeer interiors paintings, thus focusing on the four

points of departure for our plan and elevation, we may accept that we

are dealing with an older (15 or 16 century) town house at the corner

of the Molenpoort alley and a later (seventeenth century) annex

addition in the back, alongside the alley. After this addition the

grand total forms an exceptionally large house.

Entirely

separate from Vermeer interiors paintings, thus focusing on the four

points of departure for our plan and elevation, we may accept that we

are dealing with an older (15 or 16 century) town house at the corner

of the Molenpoort alley and a later (seventeenth century) annex

addition in the back, alongside the alley. After this addition the

grand total forms an exceptionally large house.

If we do take details of Vermeer's painted interiors into consideration and accept these as true views of his own house, and if we place these in our reconstruction drawings then we can actually date these architectural parts.

From details of cross-bar frames with added interior window (Vermeer catalog 1996, pages 26, 36, 128, 141, 147, 153, 187, 197 and 201) and of its location in the Studio we can conclude that the larger part of the house at the corner dated from the 16th century.

In the cross-bar frame on pages 35, 73, 52 and 171, which have been located in the Great Hall annex, we can conclude that this anex dates from the 17th century. This lower part of the house must have been demolished between 1676 and 1733.

Written 18 Juli 2001; Published online December 2002.

H.J.Zantkuijl.

Translation by Kees Kaldenbach, who provided some [text additions] in square brackets.

Postscript by Kaldenbach

In the eleventh year book of the Delft Historical Society (Elfde Jaarboek 2001 van Delfia Batavorum), p. 60-78 you will find the article by Ab Warffemius 'Jan Vermeers huis. Een poging tot reconstructie'. On page 61 of this book which appeared in 2002 he writes: "...until this day nobody has dared to make a reconstruction of the entire house." Indeed at that point Zantkuijls drawings for this web site were finished but had not yet been published online.

A comparison between Zantkuijl drawings and those by Warffemius show that they are very different: Warffemius drew the house much narrower and his annex contains rooms which according to Zantkuijl belong in the original structure. It is up to the reader to weigh the merits of both sets of plans and elevations. His information on the 1733 demolition is nevertheless quite informative.

Tiled floor patterns have not been discussed at all here. Modern literature (Fock) shows that marble floors were exceedingly rare in real architecture. Within paintings of interiors by painters such as Vermeer and De Hooch they were for free and added a stylish look.

Vermeer must have visited his patron (or mecaenas) Pieter Claeszoon van Ruijven and also visited Jannetge Jacobsdr. Vogel (?-1624) who lived at the east side of Oude Delft. According to Montias the latter house contained the stained glass window shown in two Vermeer paintings, in Brunswick / Braunschweig and Berlijn). More info under the yellow heading Artists & Patrons.

Kees Kaldenbach, September 9, 2002

*Engineer Dr.ing. Henk J. Zantkuijl was emiritus associate professor in architecture at the TU Delft. He taught architecture and restoration in Delft between 1970 to 1990.

His plans and elevations shown here and this text were produced in 2001 at the request of Kees Kaldenbach. Copyright for this text and the reconstruction drawings is by Henk J. Zantkuijl. Copyright for all other illustrations in this section belongs to the Delft municipal archives and the museums holding the paintings.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.