Town

dwellers do produce wonderful city culture - but also mountains trash and excrement.

It was crucial for Dutch health and welfare of the town to work on sanitation and get rid

of these nasty matters.

Town

dwellers do produce wonderful city culture - but also mountains trash and excrement.

It was crucial for Dutch health and welfare of the town to work on sanitation and get rid

of these nasty matters.

Town

dwellers do produce wonderful city culture - but also mountains trash and excrement.

It was crucial for Dutch health and welfare of the town to work on sanitation and get rid

of these nasty matters.

Town

dwellers do produce wonderful city culture - but also mountains trash and excrement.

It was crucial for Dutch health and welfare of the town to work on sanitation and get rid

of these nasty matters.

To the left a funny cartoon by Sweerts.

In the Delft municipal archive there are no ancient ordnances on organising trash pickup, defecation, excrement collection and transportation. Thus we cannot study the actual Delft situation for dealing with these matters. A comparison with another Dutch town is however possible, especially from the excellent book by Cor Smit on 'Smelly Leyden through the ages' Leiden met een luchtje, Straten, water, groen en afval in een Hollandse stad, 1200-2000.

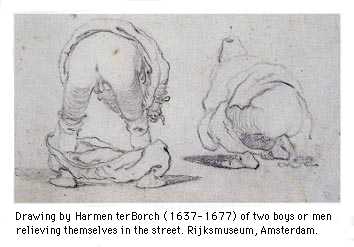

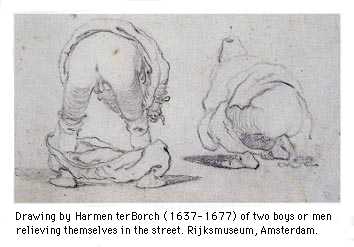

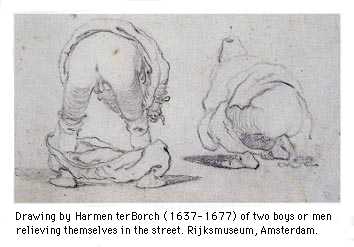

Up until 1455 the town of Leyden (and neither Delft as well I gather) was hardly paved with stone of brick and the streets were full of filth and excrement from numerous roaming cows, horses, pigs, small cattle, and poultry, but also of human beings who freely relieved themselves on the street. This necessitated wooden platform shoes (trippen)* which were bound under ones shoes. The town smelled badly, and in summer even enormously, especially when the mud was raked.

For the city dwellers learning more hygienic mores and behaviour was a matter of very slow advance through the ages. In Leyden the amount of excrement on the streets was decreased by banning cattle off the streets from the year 1455 onwards. At the side of the Vermeer house there as a little gate which served to stop roaming cattle which had escaped from the Beast Market via Burgwal. Cadavers left behind in the town formed a source of desease and filth. Slowly in a process taking centuries the streets were paved so that filth could be washed away.

In Leyden there was a dual trash retrieval system: there were city officials who cleaned the town and there were private enterprises who were hired by the town as well (Smit, p. 11, 30). The town took care of certain facilities and discussed water quality with the Provincial Water Board (Hoogheemraadschap). The trash could be composted as there was no wasteful society like we know now. Material goods were used up until entirely worn out. Household trash mainly consisted of vegetable, fruit and garden leftovers. In Delft the municipal trash and mud pits were installed just outside the East gate, in the fields. (See the yellow Delft Artists and Patrons section for the map). There may have been other private trash pits as well, which would be emptied on a regular basis.

Towns

also built outhouses above the canals (Smit, p.

37, 45, 71).

Towns

also built outhouses above the canals (Smit, p.

37, 45, 71).

In sixteenth century Delft 'cribben' of 'crebben' were installed. These are trash pits, covered over by an iron grill (one had to pay rent for these pits). Normally there was one pit for two houses but large ones were built by the city walls (De Bont, p. 101).

In most Dutch towns one could relieve oneself by the house in an open sewer which ended in a town canal. These canals had to be dredged as the filth piled up there. In Delft however there was in important beer brewing industry within the town walls which was in need of lots of clean water. Thus in Delft one did not find outhouses above canals. .

If one had a septic tank by ones own house then it would slowly fill up and it had to be emptied in a barge or a "belly-wheelbarrow"

But most of the time one would just collect one's private piss pots with excrement in the court yard - until the waste straw barge or belly-wheelbarrow would come by, loudly announced by a rattle, turned in the air by a man up front (Smit, p. 73).

Up to around 1900 animal and human excrement was sold to farmers who used it as fertilizer. The collection was well regulated by private enterprises at it was a profitable economic commodity. House dwellers were supposed to empty their chamber pots and excrement buckets in straw lined barges which passed through the canals at given times. Or into belly-wheelbarrows. But man is a creature of comfort and it will have often have happened that people did their private thing in the streets and alleys, and emptied their chamber pots into the streets or canals. A walk along the houses could be dangerous!

Ashes from the many hearths were collected separately as it formed a costly raw material for potash (Smit, p. 74).

Those who violated the rules and who dumped trash in the streets could be grassed on by other civilians, who would earn a nice informers' fee (Smit, p. 32).

The Dutch mania for scrubbing houses, sidewalks (stoops) and streets may have been a result of the Dutch tradition of keeping the cheese production rooms and objects extremely clean.

Go to the full Menu of art history tours.

*We notice a pair of 'trippen' clogs on the so called 'Arnolfini' portrait, by Van Eyck, in the National Gallery, London.

Literature:

Chris de Bont, Delfts Water, Tweeduidend jaar bewoning door waterbeheer in het Delftse. IHE, Delft / Walburg Pers Zutphen, 2000.

Cor Smit, Leiden met een luchtje, Straten, water, groen en afval in een Hollandse stad, 1200-2000, Primavera Pers, Leiden 2001.

750 jaar Delft, Delftenaren, Waanders publishers 1996, p. 203.

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.