The

Delft St Luke Guild - how it was run

The

Delft St Luke Guild - how it was run

The

Delft St Luke Guild - how it was run

The

Delft St Luke Guild - how it was runThe Guild of St. Luke building on Voldersgracht number 21, formerly the Old Mens House, was remodeled and inaugurated in 1667. Mechelen's back side looked out upon its facade. All about the physical setting, click interior.

* A digital multimedia center experience about the work of Johannes Vermeer is in the making. If all goes well it will open in the spring of 2006 in the historic town of Delft.

www.vermeerdelft.com in English

www.vermeerdelft.nl in Dutch / Nederlands

When it comes to historical documents, the Delft guild of St Luke from Vermeer’s days has been lost in the mists of time. All of the registry papers once processed by this guild were discarded after the guilds were abolished in the days of Napoleon I. This is, except for one crucial document, a small booklet, now preserved in the Royal Library, The Hague containing the member list of newly enrolled masters. It even contains some of Vermeer’s actual handwriting as he was headman during four one-year periods and within that time in 1662, 1663, 1670 and 1671 he enrolled other members.

We can however piece together the inner workings of this Delft guild as rules and regulations were broadly comparable in all Dutch towns. We are for instance well informed about how the painters’ guild was run in nearby The Hague.

Entrance arrangements

New

masters about to be tested for admission were let in and out of the building

by the Dean of the Board who took 6 stuivers per day in fee. The candidates

were given a proper test assignment and with their apprentice tools, they had

to produce their masterpiece of professional craft within a given period of

time. Those who failed the test had to wait and try and train again for a period

of 58 weeks. Normally the prouveling, passed, like Vermeer did when successfully

enrolled on 29 December 1653. After passing the board, a new master had to pay

to the guild an entry fee of either 6 or 12 guilders, the latter amount for

a master born outside Delft. Obviously Vermeer paid 6 guilders but he was not

able to come up with the full amount right away.

New

masters about to be tested for admission were let in and out of the building

by the Dean of the Board who took 6 stuivers per day in fee. The candidates

were given a proper test assignment and with their apprentice tools, they had

to produce their masterpiece of professional craft within a given period of

time. Those who failed the test had to wait and try and train again for a period

of 58 weeks. Normally the prouveling, passed, like Vermeer did when successfully

enrolled on 29 December 1653. After passing the board, a new master had to pay

to the guild an entry fee of either 6 or 12 guilders, the latter amount for

a master born outside Delft. Obviously Vermeer paid 6 guilders but he was not

able to come up with the full amount right away.

The guild laws decreed the number of years an apprentice needed to study. For the art of painting this study period was exceptionally long at 6 years. Guilds were setting and protecting quality control standards and maintained craft quality and workshop practices. Membership was reserved for males only, with the exception of widows of deceased member-artisans who were free to continue their husbands’ workshop under their own name. Widows’ names were usually not entered in the guild books. In some cases a widow would opt to marry another man who was master in the same professional field, especially when trying to save a complicated delftware manufacture workshop from going down.

Vermeer had to option but to enroll in the guild, as no economic activity as

an artist was otherwise allowed, neither in selling his own works nor in selling

paintings by other masters. The guild thus fully managed and controlled that

branch of economic activity. Thus the guild system was basically about quality

control and about economic protection, barring influx of outside ready-made

articles.

One of the pressing problems facing the Delft Guild of St Luke and Vermeer as

one of its members was the lack of a daily saleroom facility in Delft for marketing

paintings. Lacking this outlet, some Delft painters opened up their private

fore-houses so that prospective buyers could look at the stock. During just

one week in the year Delft people were free to do art trade during the big annual

fair and market. During that time the sale of paintings was allowed for all,

without restrictions.

Comparing the Situation in The Hague

In nearby The Hague sales were organized about on a more regular and larger

scale. A daily art market existed in the grand Count’s Hall (Ridderzaal)

as well as in the White Gallery near Stadhouders gate. There, the stalls for

selling paintings were often managed by wives of the painters. Trade was especially

brisk around the time of the annual fair.

Once a year a widely advertised grand sale was held in which Hague painters

could enter their works. The 1647 sale for instance, boasted some 1300 paintings,

which netted 8000 guilders at auction, at a mean price of about 6 guilders.

This annual grand sale attracted major professional art traders, but also people

with money to spare and to invest such as mayors, doctors, lawyers, artists,

and political figures like Willem Boreel from Amsterdam, one-time neighbor of

Rembrandt.

Other, smaller-scale ‘vendue’ sales during the year had to be arranged

with the Hague guild and required a listing of all of the works sold, including

the attribution to masters. Because of the large crowds and liberal beer and

wine consumption, these sales were quite popular with innkeepers as well as

with masters of the militia halls.

Within the group of guild painters one should distinguish between on one hand

fine art painters or fijnschilders, the likes of Vermeer and de Hooch,

and on the other hand kladschilders, which could be seen as house painters,

although most were also able to produce fine ornamental designs on doors and

walls. Generally the fine-art painters formed a tightly knit group, taking care

of mutual assistance in buying and selling artists materials, in valuing art

works, in restoring paintings, tipping each other off in art trade, as well

as serving as witnesses in buying and selling paintings and real estate. We

know that some liked to spend leisure time together. In the archival documents

we see that Vermeer was not the proverbial enigmatic recluse, but indeed a full

and active member of a tightly knit community of Delft artists and patrons.

Most artists worked hard at their career, and some succeeded financially and

hit the highest status jackpot when working for the Hague court or foreign courts

and thus landed extravagant commissions and high prices. Most painters just

scraped by. Painters could make additional income by teaching pupils, although

we do not know whether Vermeer had one. In a certain sense Vermeer took a middle

position as he married into a wealthy family and as one single patron decided

to favor him during many decades, buying up half of his output.

Varying from town to town the various types of craftsmen were grouped within

guilds in different ways. The St Luke’s guild in Delft contained artists

and artisans in the following very wide circle, made up of what we may term

‘creative’ workers: there were fine art painters, painting dealers,

Delftware faience manufacturers, printers, engravers, sculptors in wood - also

sculptors in stone or other fine substances such as ivory. Furthermore we find

included within this guild: architects, tapestry weavers, embroiderers, glass

makers, glass painters, glass sellers, engineers, surveyors, mapmakers, map

coloring specialists, calligraphers, typeface makers, printers, book binders,

and as the proverbial odd ones out, chair painters, and a furniture joiner.

In Delft they goldsmiths were grouped in a separate guild.

St. Luke’s Guild at Voldersgracht thus formed a HQ of a formidable economic

business and a hub of professional activity. At the Delft St Luke guild a master

in one type of trade could meet masters other branches such as those of the

rapidly expanding Delftware industry, forming a large and extremely successful

expanding group. The total number of inhabitants in Delft in 1650’s varied

between 45.000 and 50.000. Vermeer met masters from the Delftware trade and

it may be possible that he became inspired by the use of blue colors on tiles

and by the simplified outlines and strong design shapes.

Membership of the guild brought along benefits, obligations and rules. A member

was for instance not allowed to take over another member’s job except

for in cases of force majeure such as illness or drunkenness. A simple sick

benefit system existed, providing income and medical aid in case a member got

seriously ill. Members were expected to attend at funerals of other members.

Fees and fines for trespassing these rules were collected by a footman.

Having had this well-oiled guild system going since the Medieval era, town magistrates

felt comfortable in actually handing over day-to-day management to a board of

knowledgeable and able men called ‘syndics’ or ‘headmen’

of the guild. They were first elected from within the guild ranks and their

appointments were ratified by the town magistrates. Vermeer made it to this

elevated board position a number of times, starting out at a relatively young

age in 1662, 1663 and again serving in 1670 and 1671. Gathering annually in

Delft on October 18, the day of their patron saint St Luke, all members convened

and elected their future officers.

In the guild book we see that annually four headmen and from the 1640’s

on six headmen were installed, often including two or more painters. Subsequently

the Burgomasters and Aldermen OK’ed the suggested shortlist of officers

just before the end of the year. In order to settle important decisions, board

members met for official business every 4 weeks on Monday at 5 o’clock.

Not turning up when one should have done so cost each a fine of 24 stuivers.

On the Internet one may find the full clickable list of names and you can read

about their backgrounds and relationships. Please go to www.google.com and type

“Obreen + Kaldenbach”.

Artists materials

Guilds were a proud institution in city life. In mediaeval guilds held colorful

festive religious processions on Market Square several times a year. After the

protestant takeover in the 1580’s this tradition was first allowed to

continue, but it was repressed some years later on, as it harked back too much

at Saint-oriented popish religious sentiments.Fine art painters or fijnschilders

needed artist materials. Because of the very large amounts of color pigments

used in workshops in the Delftware industry, there was volume of trade and a

high level of expertise regarding these materials, both in raw form and in cleared

and refined, powdered form.

Painters could make a choice. They could invest their own time, buying raw materials

and grind these, mixing in oils and drying agents, storing these hand made paints

in pig bladders. They could also invest time and stretch and mount their own

canvases, priming them with layer upon layer of gesso, thus forming a smooth

and stable white background for canvas paintings. Because of modern techniques

such as x-ray we have come to learn a lot about the supports Vermeer used. Most

were of a standard commercial size.

Alternatively, in order to save time and to benefit from the professional expertise of others, many artists may have preferred to use the more expensive ready-made artists materials. Ground-up pigments, ready-made paints tied-up pig bladders, liquids and various sizes of canvases could be had off the shelf from specialized art dealers. These were the specialized art supply grocer nicknamed the colorman. In Delft one such colorman was Leendert Volmarijn . Alternatively a painter could shop around for raw or refined materials at the local apothecaries, who would in turn have obtained materials from wholesale colorman dealers in Amsterdam, Haarlem or Rotterdam. In 1664 Just one Delft apothecary bill crops up in Vermeer documents known to us, that of Dirck de Cocq, involving artist materials delivered to Vermeer, such as lead tin yellow and some other items.

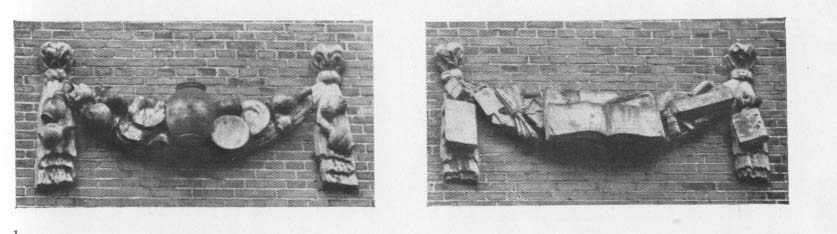

The actual building was demolished in 1876 when a town school was built on that spot - see aerial photo 1923. Another elementary school was built at that site since.

Architectural festoon ornaments salvaged from the ancient bulding are now in a wall in the south garden of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, just above the large brass letters "RIJKSMUSEUM".

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched 16 February 2005; Last update March 1, 2017. More info in the RKD site.

Top: Anonymous drawing, Washington, National Gallery of Art.

Mechelen inn was demolished and is now a vacant lot - see aerial photo 1923.