[A

large clickable version of this map is now available - choose Delft

Artists & Patrons in the yellow bar]

[A

large clickable version of this map is now available - choose Delft

Artists & Patrons in the yellow bar]This article was published in the magazine Visual Resources, Vol. XVIII, number 3, September, 2002 (actually appearing in print December, 2002).

Drs. Kees Kaldenbach

[A

large clickable version of this map is now available - choose Delft

Artists & Patrons in the yellow bar]

[A

large clickable version of this map is now available - choose Delft

Artists & Patrons in the yellow bar]

Delft, located just 10 miles southeast of The Hague, is the small and well preserved Dutch town in which the painter Johannes Vermeer (1632 1675) lived and worked. It is now known that about half of Vermeer's paintings, including many major ones, were bought by a single Delft patron, Pieter Claesz van Ruijven (1624-1674) and his wife Maria de Knuijt (who died in 1681).1 Their Vermeer paintings remained in the possession of their relatives until 1696 when 21 Vermeer paintings were auctioned off in Amsterdam. This may explain why Vermeer's best works were unknown to a wider audience during the seventeenth century and his fame was limited during his lifetime. However, some of the diary entries of 17th century travellers indicate that in certain circles outside Delft his works were known and appreciated. Vermeer's documented body of work consists of some 40 to 45 paintings, a surprisingly large percentage of which has survived. Collectors in the 18th and 19th century thought they were the works of other 17th century painters such as Metsu or De Hooch. The survival of Vermeer's paintings is indeed a credit to the discerning eye of many generations of art collectors.

Vermeer's majestic townscape The View of Delft was the first painting to be purchased by the Dutch state in 1822. It was immediately put on exhibition in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the royal cabinet of paintings, which was open to the general public. It was there that it later attracted the attention of the art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger. Initially, he was repulsed by the rough daubs of paint in some areas of the painting. However upon revisiting the gallery he soon became enthusiastic and Thoré-Bürger later went to great lengths to find information on Vermeer's life and works. He was responsible for having the first photograph ever taken of the painting - which was a difficult undertaking: "j'ai fait des folies" he wrote. In 1866 Thoré-Bürger published his first article in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and Vermeer was restored to well deserved fame.2 That article was followed by the publication of a true avalanche of articles, books and reproductions by hundreds of authors.

Vermeer has become the favorite of both the public at large and of art historians, collectors, painters and other specialists in the fine arts . He is indeed often praised as being the ultimate "painter's painter". In 1913 the painter Philip L. Hale stated: "By and large, Vermeer has more great painting qualities and fewer defects than any other painter of any time or place".3 An accomplished American painter from the east coast, Hale had developed a perceptive eye and wrote about Vermeer's paintings as crafted objects. In his 1913 book (revised and re-published posthumously in 1937) Hale also presented a compilation of archival documents about Vermeer's life and work. In 1975 the first edition appeared of Dutch art historian Albert Blankert's book on Vermeer.4 He presented all of the painter's works and their provenance (the list of former owners) as well as the text of all known archival documents relating to the life and work of the painter. Blankert's volume made an enormous impression on me and has lead to Vermeer becoming the focus of my work as an art historian.

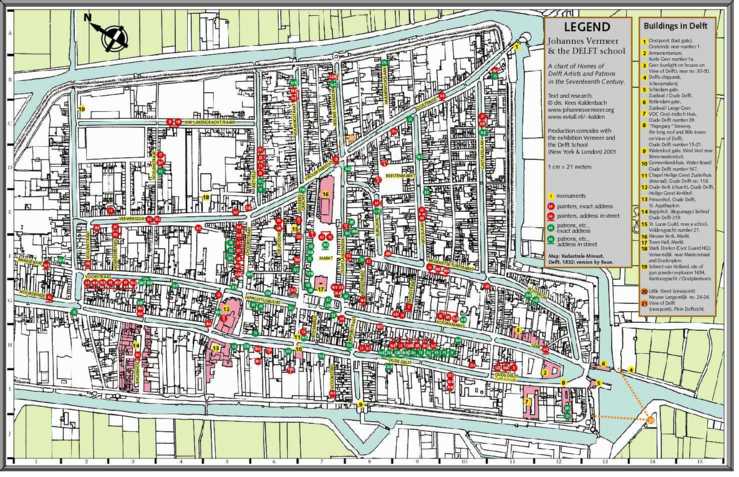

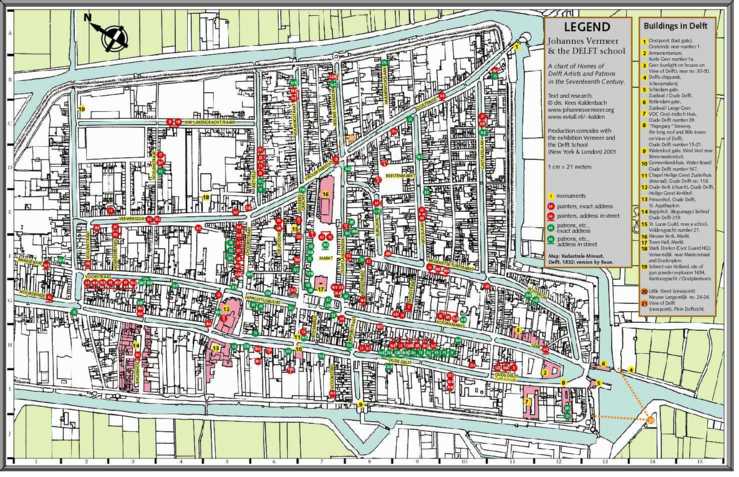

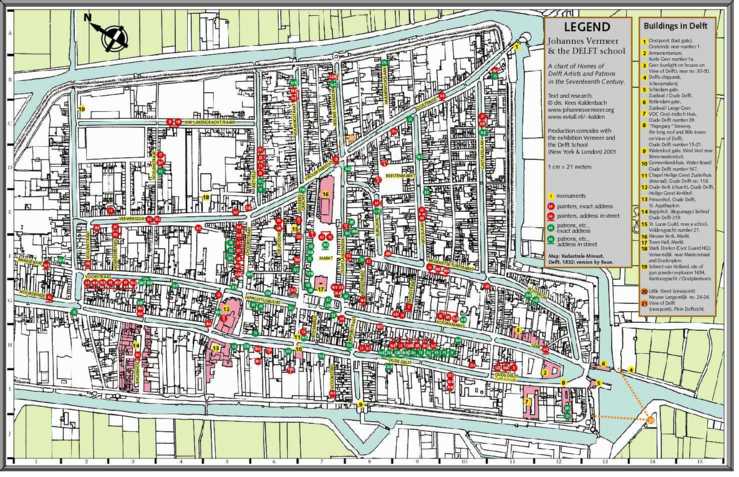

Having already published on the subject of Vermeer and 17th century Delft, the Metropolitan Museum of Art invited me to contribute material for the exhibition 'Vermeer and the Delft School'. As well as presenting a good selection of Vermeer's work, it is the first exhibition to examine his paintings in connection to artistic life in his home town, Delft. The show opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in March 2001 and then moved to the National Gallery, London in June 2001. My contribution to the exhibition catalogue consisted of an annotated map of Delft, showing the whereabouts of artists, patrons and buildings.5 This article describes how this map project began and developed into a separate wall chart published as 'Johannes Vermeer & the Delft School. A chart of Homes of Delft Artists and Patrons in the Seventeenth Century'.6

Upon its publishing, the archival research and the condensing of all of the information in one chart was rewarded by many positive reactions. The librarian of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (the Dutch state art museum) wrote that it is "a great success that this map could be published - this lavishly designed map with its extremely useful annotation". The Johannes Vermeer Foundation declared that the realization of the map "with its many layers of information of a topographical, biographical and art historical nature" was "an outstanding achievement". This foundation also agreed to underwrite the costs of printing and mailing a number of these maps.

However, this remarkable map began as a research query on a relatively limited scale. Walter Liedtke, curator at the Metropolitan and author and editor of the Vermeer catalogue, requested me to find the location in Delft of a list of some 15 individual artists and patrons. It soon became clear that very little had been published on the subject. Even that which had been published was not always trustworthy. Some printed information proved to be incorrect - such as production errors on maps in an important book on Vermeer by Blankert, Montias and Aillaud.7 This meant that archival work was necessary and the municipal archives In Delft proved to be the best source for the original documents. These Delft archives consist of a large series of separate collections, each carefully indexed. Delft also has an internet database of all baptismal, marriage and death entries, available in both Dutch and English. Their web site - www.archief.delft.nl - provides one of the most advanced online archival full search facilities in the world at no cost to the user.

[Bottom photo: The Delft Alderman for Cultural Affairs and the Director of the Delft Archive receive their copies of the map during the presentation ceremony in the Town Hall.]

The Delft archives also provided access to books written by the 17th century Delft historian Van Bleyswijck. A book with the same title and similar information was later published in Delft by Boitet.8 Recent articles and monographs on Vermeer and on the life of artists and artisans in Delft were also available there.9 The most important single author proved to be John Michael Montias, an economic historian who has devoted a great deal of time to archival research and writing on Delft painters.10

Other source material included major art history handbooks published by Thieme-Becker and Saur.11 Further archival material published by Obreen and Hofstede de Groot also proved indispensable.12 All spatial information was checked against a very large 20th century map of Delft, hanging on the wall of the Delft archives, showing all present day street names and house numbers. More and more information became available and the final addresses were incorporated on both the text manuscript and on a large manuscript map. As the project grew in scope Walter Liedtke agreed to have a large map printed as a fold-out map within the Vermeer exhibition catalogue.

Research procedure

It may be interesting to describe the ups and downs of the research procedure which led to such a remarkable body of new information. In the Delft archives, information is accessed via microfiches of hundreds of thousands of original hand-written index cards dating from the 19th and 20th century. These index cards refer to specific pages within documents. In order to protect these original documents from wear and tear ensuing searches are preferably made via microfiche files of archival documents. The most important file in this particular case proved to be the Huizenprotocol (House protocol). This file contains many thousands of handwritten pages from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century listing the various owners of real estate property. All names in the Huizenprotocol have been indexed on small cards which may be searched via microfiche. Thus my search yielded some 200 names and addresses of artists and patrons. In February 2000 John Michael Montias graciously provided an additional list of names from his personal files.

A pre-WW II treasure trove in the Delft municipal archives was the Miss P. Beydals collection. Over the years this Delft archivist had compiled an indexed filing card system. It consists of handwritten notes on any artists whose names she came across in various documents during her archival work.

Other rich sources in the archives were the Koopbrieven Huizeneigenaren (Homeowners' purchasing acts) and the Namen van Huizen (Names of Houses). The latter file system contains tens of thousands of references to individual houses. These houses were known not by number but by name only until circa 1800. An example is the case of Vermeer's patron Van Ruijven, whose house De Gouden Aecker (The Golden Acorn) on Voorstraat is now known as number 39. Sometimes the archives did not yield all the desired information. Other houses owned by Van Ruijven could be identified within a given street but not as an exact address.

Finally, unpublished manuscripts by the Dutch art historian Bredius in the State Bureau of Art History Documentation (RKD, www.rkd.nl) in The Hague also proved to be a rich source of archival notes.

When this massive amount of information on artists and patrons had been compiled, cross checked and completed, it became clear that the total amount of words in the text and notes far exceeded the amount of material which could be accommodated within the covers of the Vermeer exhibition catalogue.

Cartography

Choosing the right historical map on which to mark each house was essential. Up until this project, all books on artists in Delft have been illustrated with birds' eye view maps of Delft made by Blaeu (1649) and his later followers such as Janssonius. These are beautiful to behold and these maps do suffice for getting a general impression of Delft. The most prestigious birds' eye view of Delft was the Kaart Figuratief or Figurative Map (c. 1675). Although this map was large in size and lavish care was given to its preparation and execution it still had one drawback. It depicts a smaller number of buildings on any given block than there actually were. For our purposes of marking each house a higher accuracy was required. Pinpointing exact addresses required a large map showing every single house in Delft. The earliest historic map of this type is the 1832 Kadastrale Minuut map. From the Napoleonic era onwards maps were produced by scientific methods. This Kadastrale Minuut map was used as a tool in registering real estate ownership, and was therefore to be preferred to the more obvious bird's eye view maps. As little had changed in Delft's layout between about 1600 and 1832, this map proved to be quite suitable. In the 17th century the one area which did change radically was the northeastern corner, devastated by a tremendous gunpowder explosion on October 12 ,1654.

The lines in the original 1832 Kadastrale Minuut map are fairly thin, and would not show well in a reduced size reproduction. This is why we chose a manually drawn line copy made by Raue for his 1982 book on the early history of Delft.13 He agreed to the use of his drawing but unfortunately the original line drawing artwork had been lost. We had to revert to a painstaking process of reworking an enlarged image from his book, and then deleting the many street names with which this map image had been filled.

At the exhibition catalogue production department in New York City it was decided that the cost of mapmaking and printing of a full size fold-out copy would be prohibitive. Since there was to be no fold-out map the designer team of the catalogue production department felt it necessary to radically simplify the cartographic presentation. A new map surface was designed on which grey fields indicated larger blocks of many hundreds of houses. The designers also decided that each dot for either an artists or patrons should contain a number instead of the person's initials. At one point in the catalogue preparation, the total amount of text of the other articles had grown beyond reasonable bounds and the entire idea of a chapter on Delft topography was in jeopardy. It was doubted whether such a chapter would be worthwhile given the high map design and production costs. However, in the end the project was saved by the catalogue's author and editor, curator Walter Liedtke who secured additional funding and made a decisive case for its inclusion.

Separate map editions

Thus the production of a full scale map of Delft based on the high quality Raue version of the Kadastrale Minuut map was no longer possible, and the situation looked bleak. The costs of creating a large map from scratch, electronically entering dots for 120 artists and 120 patrons and the ensuing full color printing seemed prohibitive. Contact was then renewed with Willem van der Kooij, Editor-in- chief of the Delft newspaper the Delftsche Courant. Would his newspaper be interested in printing a double spread color map of Delft? His immediate response was positive and he set the necessary wheels in motion. After budget calculations by the newspaper's management and deciding on a publicity plan devised by the publisher's public relations department it was decided that the map project was on. This extraordinary production would be presented as special service to the newspaper's readers. At the same time the map would also be printed in a separate print run on high quality paper. This edition of the map was to be available at the newspaper office at a low price.

Rob Hofland, a graphic designer from the Delft newspapers' lay-out department, was also involved from the very start of the planning and production phase. His expertise contributed to ingenious solutions in combining the various layers of topographical, biographical and art historical elements into a single yet coherent visual resource. The Raue version of the Kadastrale Minuut map (see above) was reduced in size and scanned into a computer. The various dots with initials and numbers were then electronically superimposed on the map. They show the locations of artists (red dots) and patrons (green dots) living in Delft during the seventeenth century. Some 20 buildings (yellow dots) were indicated. Two of Vermeer's townscapes were pinpointed as stand-points and fields of vision (orange dots and lines). Whereas buildings were simply numbered in their yellow circles, persons (both the artists in red and patrons in green) were indicated with their initials for quick referral to the extensive list printed on the reverse side of the map.

The Dutch edition of the map was thus secured, but the sizeable body of new archival research still merited an English edition. The Delftsche Courant 's publisher had no commercial interest in an English edition. Its loyalty was towards its own Dutch readers and not to an international public. However, dr. Albert Blankert of the Johannes Vermeer foundation understood this obstacle and offered welcome financial support which made the English edition possible after all.

Thus the map was designed and printed, not only as a newspaper supplement in the Delftsche Courant but also as separate high quality editions in Dutch and English. On March 30 2001 these maps were presented to a number of dignitaries during a short ceremony in the Mayor's office at the Delft City Hall. Dating from 1620, this City Hall was a fitting historical setting for this project - for some three hundred and thirty years ago a group of Delft mayors, probably meeting in this very room, had decided to produce the large, costly and impressive Kaart Figuratief map.

On March 31, 2001 the double-sided map with its two full pages of listings of artists and patrons on the reverse side were printed as a supplement in the Delft newspaper and distributed to all its subscribers.

Due to its importance in teaching local history to school children two laminated copies of the Dutch edition were donated by the Johannes Vermeer foundation to fifty-five schools in Delft. Two complimentary copies of the map in the English edition were later distributed worldwide to eighty major art history libraries and art museums.

Useful tool

As indicated by the response of the Rijksmuseum librarian, this map has indeed become a useful tool. It contains three precise addresses for Vermeer and two for De Hooch. The map presents the first exact addresses for the Delft painter Leonaert Bramer as well as those for many dozens of other less famous painters. It also pinpoints 20 important buildings and identifies the location for two Vermeer townscape paintings.

The exact spot of the building shown in his famous townscape The Little Street is marked, having been pinpointed with accuracy in my recent article.14 Understanding Vermeer's largest townscape, The View of Delft, is also improved by information in this map. A long horizontal roof is visible on the left-hand side of this painting. It has now become clear that this building with its slender tower, known as 'The Parrot' was the home of fleet Admiral Cornelis Tromp and his mother - and possibly also of his father, the famous fleet Admiral Maarten Harpertsz Tromp. Finally the map presents the cream of the Delft patrons as well.

Its use as a tool has also been secured by proper design decisions. The outer edges of the map provide a strong visual boundary, similar to those found in a 1950s style of atlas map. The mapmaker's legend is found on the right hand top side. Rob Hofland designed this legend in a grey field and he also moved the text of the list of 20 buildings, originally planned for the reverse side, to the front on a grey field next to the legend. On the map itself he created a visual shorthand for two types of initialed address dots. Each plain dot indicates an exact address and each underscored dot represents an address on a given street. All initials within both red and green dots are echoed on the reverse of the map where circa 250 individual captions are listed, stating the addresses of artists and patrons along with biographical details. At a glance one can see the area of the devastating gunpowder explosion of 1654.

Although the map is both visually attractive and an important art historical source, it does not really read like a novel or a handbook. The sheer volume of unknown names of artists and patrons would soon confuse the general reader. This map and its long caption list works best when used alongside a book on Delft artists. Being able to pinpoint these artists - whose names are often unfamiliar - would help the reader in memorizing characters and their location within 17th century Delft.

With its spatial grouping of artists and patron, this map also reveals the surprising social structure of the living conditions of artists and patrons. Patrons preferred living in houses built along the major canal Oude Delft and another canal which also runs parallel like a double spine from north to south. This district was the wealthy quarter of Delft. Other parts of town, especially the northern, eastern and south-eastern quarter contained the lower income houses.

Painters chose houses with a studio which has northern exposure. They prefer it because that light changes the least in what is now called "color temperature" from sunrise via high noon to dusk. This means that the hues and values of their oil paint can be recognized by the same color of light all day long. Most houses in Dutch towns are built closely together. They are aligned in such a way that light only enters the house from either the street side or from the garden side. That is why the painter's studio would be located at either end of the house. In any street which runs from east to west, northern light can be found on either the garden side of the northern block of houses - or at the street side of the southern block of houses. This is obvious on such streets as the Choorstraat in Delft on which a remarkable number of artists lived. Please note that on this map the north is not on top but on the upper left hand corner.

Most of Vermeer's works were created in his studio at the Oude Langendijk address. He lived there from 1660 or before, until his death in 1675- see the dot marked JV4. The Kaart Figuratief shows this building as long and narrow, running from east to west. But the Kadastrale Minuut shows a wide building which does not extend very far to the back. There was an alley on the west side; the Molenpoort, now called Jozefstraat. Sadly, this block of buildings has been demolished. It would be interesting to visually re-create the floor plans of the Vermeer house.15 This would be feasible because of the full documentation of the Vermeer inventory, recorded room by room.

Web site

A full size image of the maps in English and Dutch and the full text of all captions of this Delft map are now available for free on Internet. As an added bonus a complete list of all painters in the St Luke Guild, organized both chronologically and alphabetically can also be found there - with cross indexes and copious research notes on the homes of individual painters. These notes were too voluminous for inclusion in either the newspaper or the high quality printed maps.

The contents of this part of the web site is extremely rich and varied in images and text information. However, the web site technology involved is still quite basic. It is driven by HTML code with its fast blue hyperlinks. Information on all artists and patrons can be addressed within seconds by use of the dropdown boxes. More advanced technology may be worthwhile in future, but constraints on time and funds has prevented the creation of an interactive system. The current web site also doesn't yet permit clicking on the map in order to open up moving texts and images. Flash technology would probably be the proper technology for this next step forward. The author invites proposals and help from readers for developing these next phases.

The author's involvement with Johannes Vermeer and the city of Delft has been going on for some 25 years. From 1982 on results of this research on the topography of Delft and Vermeer have been published in various scholarly journals. For the general public multi-lingual presentations (in English, German, Dutch and French) of these texts are now available on Internet. For instance one may tour The View of Delft or read a discussion on an exact dating of this painting based on an analysis of the ships and other items. A detailed archeological account supported by some 15 reasons proposes an exact location for Little Street . Other projects on the web site include a series of stills from a 3D flight over Delft. The latest addition presents QuickTime movies showing a unique project in the field of art history, done in cooperation with Delft Polytechnic University. These QuickTime movies show various 3D walks through historical drawings and prints of the area around The View of Delft. Readers are cordially invited to visit this on the www.johannesvermeer.info web site.

1) John Michael Montias, Vermeer and his Milieu, A Web of Social History, Princeton, 1989.

2) Théophile Thoré-Bürger, Gazette des beaux-arts 21 (Oct.-Dec. 1866) pp. 297-330, 458-470, 542-575.

3) Philip L. Hale, Vermeer. London, 1937, p. 3. "There were giants, of course, such as Vélasquez, Rubens and Rembrandt, who did very wonderful things, but none of these ever conceived of arriving a tone by an exquisitely just relation of colour values - the essence of contemporary painting that is really good. (...) We of today particularly admire Vermeer because he has attacked what seem to us significant problems or motives, and has solved them, on the whole, as we like to see them solved. (...) By and large, Vermeer has more great painting qualities and fewer defects than any other painter of any time or place." (Text from the 1937 edition completed by F.W. Coburn & R.T. Hale; original publication 1913).

4) Albert Blankert, Johannes Vermeer, Het Spectrum, Utrecht/Antwerp 1975. Subsequently other editions of this Dutch book were printed such as Vermeer of Delft, complete edition of the paintings, Phaidon, Oxford, 1978.

5) Kees Kaldenbach, 'Plans of Seventeenth-Century Delft with Locations of Major Monuments and Addresses of Artists and Patrons' in Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School, exhibition catalogue, New York/ New Haven, 2001, pp. 557-565.

6) Kees Kaldenbach, Johannes Vermeer & the Delft School. A chart of Homes of Delft Artists and Patrons in the Seventeenth Century, Amsterdam 2001. Published by the author.

7) Albert Blankert, John Michael Montias, Gilles Aillaud, Vermeer, Editions Hazan, Paris 1986 / Rizzoli, New York 1987, 22-23. On page 22 the site of the powder magazine is marked incorrectly. On page 23 the "Three Hammers" and the home of Maria Thins are erroneously indicated. For correct information see the author's internet site.

8) Dirck Evertsz. van Bleyswijck, Beschryvinge der stadt Delft (2 vols.) Delft, 1667 (-1680). Updated by Reinier Boitet, Beschryving der Stadt Delft, Delft 1729.

9) For a recent bibliography see Walter Liedtke, Vermeer and the Delft School, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/ New Haven, 2001.

10) For another recent bibliography see John Michael Montias, Vermeer and his Milieu, A Web of Social History, Princeton 1989. Its Dutch edition Vermeer en zijn Milieu (Baarn, 1993) is the updated version.

11) U. Thieme, and F. Becker, Allgemeine Lexicon der Bildenden Künstler (...). Leipzig, 1911-1950 and K.G. Saur, Allgemeine Künstler Lexicon, Saur, München-Leipzig 1992-( ).

12) D.O. Obreen (ed.), Archief voor Nederlandsche kunstgeschiedenis, 7 vols, Rotterdam, 1877-1890. Hofstede de Groot, Quellenstudien, 1897. Abraham Bredius, Unpublished manuscripts, Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie (RKD), The Hague.

13) Raue, J.J. De Stad Delft, vorming en ruimtelijke ontwikkeling in de late middeleeuwen, interpretatie van 25 jaar binnenstadsonderzoek, Delftse Universitaire Pers, Delft,1982.

14) 'Het Straatje van Johannes Vermeer: Nieuwe Langendijk 24-26? Een kunsthistorische visie op een archeologisch en bouwhistorisch onderzoek' in Bulletin KNOB (Koninklijk Nederlandse Oudheidkundige Bond), Vol. 99 nr. 5-6, november-december 2000, p. 239-249. A translation is available on Internet.

15) I am presently working on this new visualisation project.

[This part of the web site opens on January 17, 2003].

-------end of notes-------

*Availability of this wall chart

This outstanding cultural heritage chart of Delft is now available for free on internet as a large printable color jpg image at the www.johannesvermeer.info or www.xs4all.nl/~kalden web sites.

It is also available as a handsome 75 cm wide print on high grade luxury paper, in both Dutch and English editions. Some 120 painters in the Delft Guild of St Luke and 120 of their clients are pinpointed, along with 20 buildings such as the site of the 1654 gunpowder explosion. This map is also the first to show the exact address of Vermeer's 'Little Street', erroneously omitted from the map within the Vermeer exhibition catalogue. For further information please contact Kees Kaldenbach at kalden@xs4all.nl by e-mail.

This page launched 2002. Update 22 feb. 2013

Research and copyright by Kaldenbach. A full presentation is on view at www.xs4all.nl/~kalden/