Vermeer and Catherina Bolnes* went trough a period of courtship before their marriage in 1653. Johannes Vermeer was only 20 years old and thus relatively young when he married: generally the age of men was between 25 and 30 years for their first wedding (Carasso, p. 4).

Did the courtship and marriage of Johannes and Catharina take place in a peaceful atmosphere? Not quite so. In the document dated April 5, 1653 we read that Maria Thins, being Trijntgen / Catherina Bolnes' mother had objections to the intended marriage. In this document the painter Leonard Bramer according to traditional views made an attempt at mediation in order to ask Maria Thins to give her consent. Is this reading correct?

In Holland youngsters did normally choose their own partners; they were not forced into an arranged marriage. It is true that parents would sometimes see a future marriage partner als less fitting. Maria Thins probably felt that Vermeer was too young, economically of a different class, not yet on his feet for a decent family income and last but not least - not of the desired Roman Catholic religion.

And yet, on April 20 the Roman Catholic marriage of the two took place anyway at the village of Schipluiden. There, Maria Thins did not sign the document. The marriage document was however appended 5 days later with this text: "5 en 20 april 1652. Den 5den Apprill 1653: Johannes Reyniersz. Vermeer J[ong] M[an] opt Marcktveld, Catherina Bolenes J[ong] D[ochter] mede aldaar."

The Latter two words: "also living there" indicate in Mechelen inn at Market square. John Michael Montias, referring to the "also living there," states on p.101 : "The clerk's inaccuracy is more likely, in my judgment, than the possibility that Catharina was staying at the inn kept by Renyier Janz., let alone that she was cohabiting with her fiancé." However, for this discussion we will now accept that the clerk was writing the plain truth.

Cohabiting?

The words 'also living there' then show that Catharina had probably run away from home (possibly before April 20) and that she had already started cohabiting with Vermeer in the inn 'Mechelen' on Market square, - in short that Johannes Vermeer had 'abducted' his beloved Catharina at just a stone's throw distance - and that Catharina had consented to this elopement.

This gave a definate twist to the prior engagement situation so that Maria Thins, considering Catharina's legally adult age, did not have any formal grounds for barring the intended marriage. Later on, there was clearly no personal discord between Vermeer and Maria Thins, for in or before 1660 the married couple started living right in Maria Thins' large house at Oude Langendijk. Legally all was fixed in 1661 when Maria Thins was in the town of Gouda and had the marriage ratified so that a future heritage situation would not present any problems.

Why did Catharina cohabit or elope - or to put it in other words - find sanctuary and romance - in Mechelen inn? Perhaps formerly the home situation in Gouda with the abusive nature of both her father and her brother Willem Bolnes was too much for her? And in Delft perhaps her mother Maria Thins may have been to dominant?

By marrying Johannes Vermeer himself also gained much. The legal age for being considered an adult was normally 25 but it was immediately effective when marrying. Thus at the tender age of 20 Vermeer did not remain dependent on his mother. By marrying he became legally of age (in the sense of legally adult and ready to act in society) so he could legally run the the art trade of his father who had died one year earlier - and try to make an independent living. Perhaps he may have helped his mother in running the inn but we see that he sold Mechelen Inn right after his mother died. (Lindenburg, p. 93-97)

In the course of their marriage which lasted from 1653 to 1675 the couple had given birth to fifteen children. Eleven of these, an exceptionally high number, were alive in 1676 and the eldest of these must have been of the courting age by then. In the Vermeer home matters of courtship and love must have been a theme. No letters or diaries have come down to us which would shed light on life in their home. This text focuses on a few available historical sources.

Nevertheless men and women, if they chose to do so, could do birth control by obtaining certain herbs from the apothecary. "If the apothecary would not provide certain herbs, a lot of children would be born." [ Dutch:"Waerder inde apteeck gheen heymelick cruytt, wat zouder menigh kinnercken comen uyt"] was a naughty rhyme once written by a citizen. (Ach lieve tijd, Delft, 1995, p. 12).

How

much leeway was given to the youngsters in the field of love

life?

How

much leeway was given to the youngsters in the field of love

life?

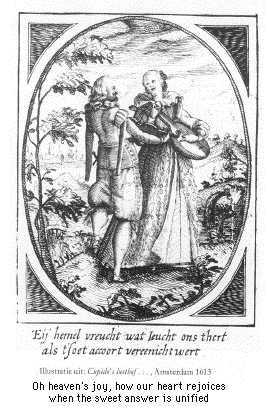

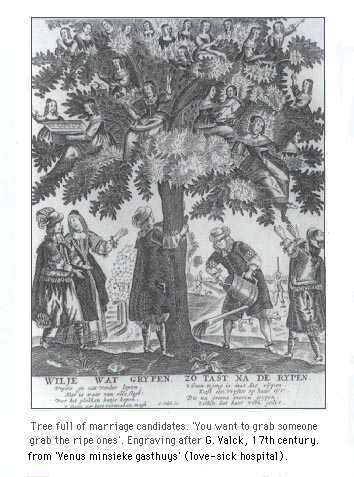

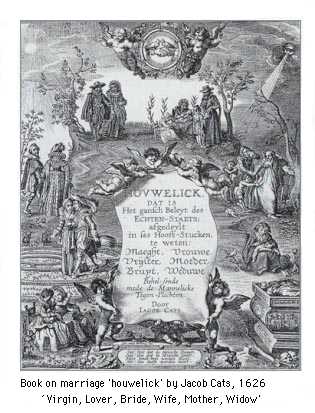

In Dutch culture, many emblem books such as the one shown to the right and a great many other moralizing and admonishing books were published - dealing also with the dangers of the meeting of the sexes. But there are hardly any diaries and letters on the ideas and practices governing this area of life. We do however find some useful descriptions in depositions written by the Notary public. Because of the lack of a properly functioning police force, incidents in society were noted this way. Thus these archival sources do shed light on how people actually behaved. Other sources are diaries and books by foreign travellers.

In 1669 the traveler William Aglionby noted the prevailing Dutch licentiousness: "Girls are allowed to walk the streets at night with their boyfriends , and in winter they go out skating with their young men, they often spend the night in an inn in a suburb or even another town". (Datema, British Travellers, p. 158.)

A fascinating 'slice of life' can be seen in the village of Graft in the flat green polders of North-Holland. There, just after midwinter, a group of adolescent boys and girls joined eachother for a major excursion in a large ice sled (the date being January 28, 1691). These boys and girls belonged to the religious group of Mennonites. They were seven unmarried boys and girls in the age group between 17 and 20 years old, who were 'seeing each other'. They went on their journey unattended by adults. Setting off for the village of Landsmeer after at 4 o'clock in the afternoon (thus after the ending of church services, when the day light was faltering) they were all sitting in their large, presumably horse pulled sled which must have had at least one lantern. And they would only return well after midnight. Obviously this kind of night time excursion was probably seen as a normal way of passing leisure time among adolescents (Van Deursen, Graft, p. 227).

Young

ones were told by parents and other family members that they had to

guard the reputation of their family by their good conduct. Family

ties were of the utmost importance as in the harsh world outside

family circles there were hardly any institutions to give assistance

in case of loss of income, when falling ill or becoming crippled

(Kooijmans, Vriendschap, p.

61).

Young

ones were told by parents and other family members that they had to

guard the reputation of their family by their good conduct. Family

ties were of the utmost importance as in the harsh world outside

family circles there were hardly any institutions to give assistance

in case of loss of income, when falling ill or becoming crippled

(Kooijmans, Vriendschap, p.

61).

During the winter months mixed-sex evening meetings were organized for youngsters, called "spin-avonden". Girls got together to spin yarns. Around nine o clock at night the boys came by to join the girls and various games were played. (Speet, p. 139).

Dance schools and dance halls were popular in towns and villages (Van Deursen, Kopergeld, 106).

In choosing a partner one had to take ones direct family members into consideration, but opinions of ones friends and neighbors were also of importance. If and when the young man was accepted by the girl's parents then the 'window courtship' or "venstervrijen" occored: The suitor was allowed entrance to the bedroom through the window and left early the next morning. Premarital sex was ubiquitous - against offical stance. When a girl got "tried out" by a boyfriend and actually got pregnant, then procreation was assured and a marriage was soon fixed. (Speet, p. 138, 139).

With regards to courtship an appreciable latitude of behaviour existed in the Republic (as compared to other western European countries, especially those of the Mediterranean). Youngsters, especially those in agricultural regions, often took initiative in courtship. This nightly visiting was called 'kweesten' [from the root 'quest']. When a young couple had bedded each other, and the girl had become pregnant, a wedding was to follow (Van Deursen, Graft, p. 230). According to Spies this custom was however no longer accepted in urban areas (Spies, p. 32).

In towns there were also quite decent, non-sexual courtships. In 1632 Barbara Adriaens (born 1611) declared before an Amsterdam court that during her courtship and prenuptials she had never touched or kissed her partner in an indecent manner, but she only kissed the way a female and male lover are wont to do.

The fact however that Barbara was a woman who presented herself as a man and even got married to a woman was a transgression severely punished by the magistrates. (Van Stipriaan, Ooggetuigen, p. 162-163).

After a period of 'getting to know each other' and of courtship of a 'normal' couple the engagement followed.

The 1580 law concerning marriage in the State of Holland stipulated parental consent if the boy was under 23 or the girl was onder 20 years old. (Speet, p. 141). In settling and signing the prenuptials, which was the next phase, small but meaningful objects were exchanged such as a cloth with a knot. Annulling the intended relationship in that phase was considered a grave breach of etiquette. If there was money in the family then prenuptials were noted. These included the setting of the dowry and the Widow Fund, the "douarie", being the money payable to the wife if the busband were to die first in marriage. This document was drawn up in the presence of a notary or a clergyman (Speet, p. 141).

Wedding

Wedding

A wedding could be held either in a church or in a town hall (Van Deursen, Kopergeld, p. 114).

The wedding itself was not only a matter for the family but also for neighborhood. Neighbors assisted in organizing the wedding. There was ample food and drink and there was live music to which all could dance. Specials songs were chanted from song books for weddings. At night the bridal pair were danced towards their bed but after that, the newlyweds were often annoyed by drunk wedding guests who came to the door with rowdy jokes. (Speet, p. 142, 144).

Later on, for birth control, one could choose several methods: abstinence ; restricting lovemaking to certain days of the woman's monthly cycle ; practicing the unsafe coitus interruptus, or using the syringe. See a unique Dutch example of a wooden v@ginal syringe from the seventeenth century.

Married life

In his book Friendship ('Vriendschap', 1997) Kooijmans states that a pre-requisite for a good marriage was a close fit between the partners regarding age, social status and religion. Marriage was a bond based not upon passion but essentially a contract which arranged procreation, followed by raising and taking care of the offspring. Partners in marriage agreed to run a household in a sensible manner. Within the family one aimed to safeguard the family capital, status and reputation. There was a traditional division of roles between husband, who provided income and who guarded the combined capital and the wife who managed the household, Capital was often separated in the marriage settlement.

"An inventory was made of the capital which was brought into the marriage by both parties, and commonly it was declared that after the dissolution of the marriage the initial sum would be returned to the original family. Gains and losses made in the mean time were most often shared, but the wife had the option of choosing, after her husband's death, whether or not to share in profit or loss." (Kooijmans 1997, p. 149).

Based on archival documents, Kooijmans discusses the long, fruitful and happy marriage which was entered in 1656 between Joan Huydecoper and Sophia Coymans. Fascinatingly, father Huydecoper not only maintained a financial bookkeeping but also a fully fledged 'social bookkeeping' covering all reciprocal manners of favours and obligations encountered in society. Nine months after the wedding, when their first son was born, the father noted the names of the godparents and their deferred gifts ('pillengiften'*). It is quite remarkable that Huydecoper also kept track of the number of times he made love to his wife, which he entered with the "c" of coitus [making love]. During the year 1659 he noted 75 times "c". During a pregnancy the "c" continues up to the eighth month. In total Sophia Coymans had at least eleven pregnancies, and of her children seven survived (Kooijmans 1997, p. 152, 153).

"It was expected of daughters that by entering into a good marriage they would help the family to a worthy alliance - and that they would further this by showing themselves a devoted and sensible wife and mother". Children were the incarnation of a family's future; investments in them - in education, training and their well-being - were not only geared to their individual qualities but especially for what they represented. (Kooijmans, Vriendschap, 1997, p. 166, 168).

In the book Houwelijck (Marriage) Jacob Cats describes how - within the early months of marriage - the woman had to transform herself from vrijster (courtship girl) to vrouwe (housewife, house manager).

Read about pregnancy and midwifes.

See a stunning milk-cure against worms.

Pillegift = Gift made by godfather and godmother, deferred until the moment (up to a year leter) the child was expected to survive. Historical documents including this and other terms can be found on the Dutch Royal Library's web site (Koninlijke Bibliotheek) http://www.kb.nl/kb/kbschool/hr/site/zoek.gen.html

Update June 8, 2011.

Literature

Boheemen, Petra van (ed), Kent, en versint. Eer dat datje mint. Vrijen en trouwen 1500-1800. Waanders. Zwolle; Historisch Museum Marialust, Apeldoorn, no year.

Dedalo Carasso and Annemarie de Wildt. Een kind onder het hart ; zwangerschap en gebooprte in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Exh. Cat. Amsterdams Historisch Museum, 1987.

Jacob Cats' Houwelick (...) 1625. Cats discusses rights and duties of women in six phases of life, being virgin, lover, bride, woman, mother, widow - and also discusses the male counterparts.

C. Datema, 'British Travellers in Holland during the Stuart period. Edward Browne and John Locke as tourists in the United Provinces'. Thesis, Amsterdam Vrije Universiteit, 1989.

A.Th. van Deursen. Een dorp in de polder. Graft in de zeventiende eeuw. Bakker, Amsterdam, 1994.

A.Th. van Deursen, Mensen van klein vermogen; Het 'kopergeld' van de Gouden Eeuw, Ooievaar/Prometheus, Amsterdam, 1991.

Luuc Kooijmans, Vriendschap en de kunst van het overleven in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Amsterdam, Bert Bakker, 1997.

Drs. M.A. Lindenburg, 'Het huwelijk van Jan Vermeer' in Delfia Batavorum, Dertiende Jaarboek 2003, Historische Vereniging Delfia Batavorum, Delft 2004, p. 93-97.

Montias, J.M., Vermeer and his Milieu, A Web of Social History, Princeton 1989.

Ben Speet (red.) 20 eeuwen Nederland en de Nederlanders. Deel 6: Geboorte, huwelijk en dood. Waanders Uitgeverij, Zwolle ism. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1998.

Marijke Spies, Des mensen Op-en Nedergang, literatuur en leven in de Nooordelijke Nederlanden in de zeventiende eeuw. Bulkboek Amsterdam/Barneveld, 2nd ed. 1985.

René van Stipriaan, Ooggetuigen van de Gouden Eeuw in meer dan honderd reportages, Prometheus Amsterdam, 2000.

*Did Catherina call herself Catherina Bolnes or Catherina Vermeer? Van Deursen has noted that women in the village of Graft held on to their own last names - or patronims such as Jansz. during the seventeenth century. (Van Deursen, p. 42).

This page forms part of a large encyclopedic site on Vermeer and Delft. Research by Drs. Kees Kaldenbach (email). A full presentation is on view at johannesvermeer.info.

Launched December, 2002; Last update March 1, 2017.

Back to the Welcome page: click Welcome.